The German Book Prize

The longlist – the bottom line

Literature prizes are all well and good, but it isn’t always the case that the prize-winners are also the most successful books: let’s look back at the German Book Prize over the last ten years.

By Matthias Bischoff

At the Olympics there’s no doubt – the gold medal goes to the fastest runner. This approach is impossible with a prize for the “best novel of the year”. The range of winners of the German Book Prize varies from accessible works to elite literature; and jury success can sometimes differ significantly from success on the book market. We look back at the award-winners over the past ten years:

Eugen Ruge: In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts (2011)

A Deutschlandroman, a sophisticated and ambitious work that quickly became a widely-read classic.

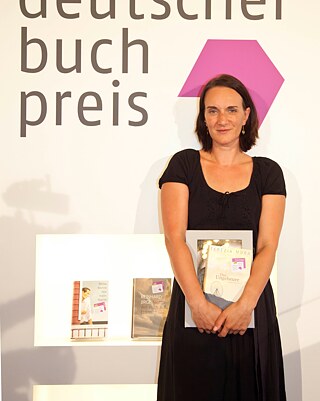

Ursula Krechel: Landgericht (2012)

Landgericht was a deserving winner. Yet at the same time 2012 was such a strong literary year that it would have been possible to pick half a dozen “best novels”, and that highlights an unsolvable problem with the award: high-calibre novels like Wolfgang Herrndorf’s Sand or Stephan Thome’s Fliehkräfte (Centrifugal Forces), Indigo by Clemens J.Setz and Nichts Weißes (Nothing White) by Ulf Erdmann Ziegler were all published at the same time. On the other hand Jenny Erpenbeck’s Aller Tage Abend (The End of Days) only made it to the longlist – just like Olga Grjasnowa’s debut novel Der Russe ist einer, der Birken liebt (All Russians Love Birch Trees), which was highly commended by critics.

Terézia Mora: Das Ungeheuer (2013)

The novel impressed the jury with the contrast between the two voices and the balance of sad yet frequently comical scenes. This humorous touch is often much needed since the author has clearly studied in fine detail what depression does to people, and thus the passages about Flora repeatedly describe this with an almost clinical precision which does wear thin after a while, and there is soon a sense that nothing new is being revealed.

Lutz Seiler: Kruso (2014)

With Kruso, Seiler has managed to produce a work of art that has become a rarity in German contemporary literature: he is a recognisable person, a character with all his contradictory aspects almost as you might expect in a 19th century realist novel – yet never old-fashioned. Kruso is not a role model and despite his anarchistic tendencies does not represent a particular principle: he’s just a person. Creating this kind of character is something that German authors are rarely brave enough to attempt – unlike writers in English-speaking countries, for instance.

Frank Witzel: Die Erfindung der Roten Armee Fraktion durch einen manisch-depressiven Teenager im Sommer 1969 (2015)

Critics were impressed, copies were selling fast – but whether or not the volume was actually read by its buyers is unknown. But with this novel there’s something you can do that really you could do with any book but here it’s pretty much essential: you can skip or skim entire chapters in order to immerse yourself even more deeply in others (for example the fascinatingly idiosyncratic interpretation of the Beatles masterpiece “Sgt. Pepper”). It’s a book reminiscent of a lucky bag.

Bodo Kirchhoff: Widerfahrnis (2016)

The fact that the substantial novel Die Liebe in groben Zügen (Love in Broad Strokes) by Bodo Kirchhoff, now considered one of his most important works, never even made it to the shortlist in 2012 ranks amongst the most puzzling of decisions by the jury to date. Maybe they realised too late what a masterpiece they were relegating to the also-rans. A rather clumsy attempt to make good this mistake was undertaken four years later, when Kirchhoff received the Book of the Year award for his short story Widerfahrnis, one of Kirchhoff’s less important works.

Robert Menasse: Die Hauptstadt (2017)

Although the reader learns and understands, they are always left with a slightly bitter aftertaste: all these figures are holders of office and do not appear especially three-dimensional. They fulfil a purpose that involves depicting the EU situation rather than exploring their characters – ultimately the novel does lack epic impact in this department.

Inger-Maria Mahlke: Archipel (2018)

Old-fashioned though it might sound: Archipel (Archipelago) is totally unsuitable for readers who “want to know what happens next”. And it gets worse – the achronological narrative structure means the reader is always a step ahead of the book characters. Sometimes that’s a good thing – but at the end of the day interest does wane a little and the underlying reason behind the process is not immediately apparent.

Saša Stanišic: Herkunft (2019)

In this way many impressions combine to form a portrait of the lost Heimat (homeland), but equally of an uncritical and in no way bitter image of Germany as an immigration country. This is why Stanišic also quite deliberately talks about Heimat in the plural form in his book, which is part novel, part autobiography and very often just exquisitely imaginative storytelling.

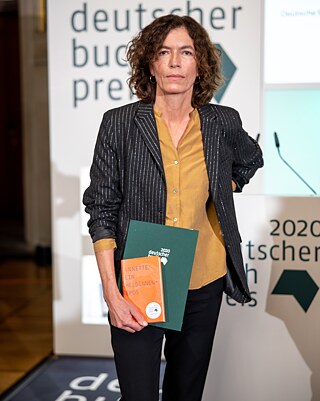

Anne Weber: Annette, ein Heldinnenepos (2020)

Weber writes in verse, and whilst not rhyming it is rhythmically structured throughout to create a distance in which she maintains a clever balance between admiration of the headstrong woman and questions about the limitations of life in an ongoing state of resistance against the prevailing circumstances. The truth is that for Anne Weber – who has lived in Paris for many years – this is not primarily about writing a biography, it’s about an exemplary life, an individual constantly coming to terms with the society in which they live.