Artificial Intelligence in Foreign Language Teaching

How is the role of teachers changing as a result of the application of artificial intelligence?

Prof Dr. Torben Schmidt is an important voice in the field of digital foreign language learning. In an interview with Dr. Moritz Dittmeyer, he discusses the potential and the challenges of AI technologies in foreign language learning.

By Dr. Moritz Dittmeyer

Artificial intelligence is omnipresent. Thanks to ongoing advances in technology, especially in the field of natural language processing, and the ability to process gigantic volumes of data, more and more digital tools and programs are being developed to assist us in everyday oral and written language tasks.

How do these developments affect the learning and teaching of foreign languages? Which AI technologies are best suited for use in foreign language learning and what are the biggest challenges involved in using them for this purpose? And what does all this mean for teachers of face-to-face and online courses?

Dr. Torben Schmidt, professor of English language didactics | Leuphana Universität Lüneburg

Torben Schmidt is a professor of English language didactics at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany. He spoke to AI specialist Moritz Dittmeyer at the Goethe-Lab Sprache (Goethe-Institut Language Lab), an interdisciplinary unit for innovation, about research in and testing of digital learning technologies.

Dr. Torben Schmidt, professor of English language didactics | Leuphana Universität Lüneburg

Torben Schmidt is a professor of English language didactics at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany. He spoke to AI specialist Moritz Dittmeyer at the Goethe-Lab Sprache (Goethe-Institut Language Lab), an interdisciplinary unit for innovation, about research in and testing of digital learning technologies.

Professor Schmidt, you’re a professor of English language teaching. Given the big developments in recent years, what aspects of technology-assisted English learning and teaching can we apply to German?

The methods of teaching different foreign languages, especially English and German, are not worlds apart. We really are a big community, and all the more so insofar as there’s something very unifying about digital learning. The academic discourse is similar across different disciplines and languages.

Then again, I think we do have certain obvious advantages in English teaching: first of all, owing to the fact that there are significantly more English speakers. We also have far more professorships in linguistics and far more projects in computational linguistics.

Thanks to these factors, we researchers in English teaching have been able to make a difference in recent years, especially in computer-assisted foreign language learning.

Can you briefly explain what computer-assisted foreign language learning is?

The term “computer-assisted language learning”, or CALL for short, is nothing new; it’s been around for several decades now. Generally speaking, it’s about forms and methods of learning and teaching foreign languages. I’d break it down into three areas:

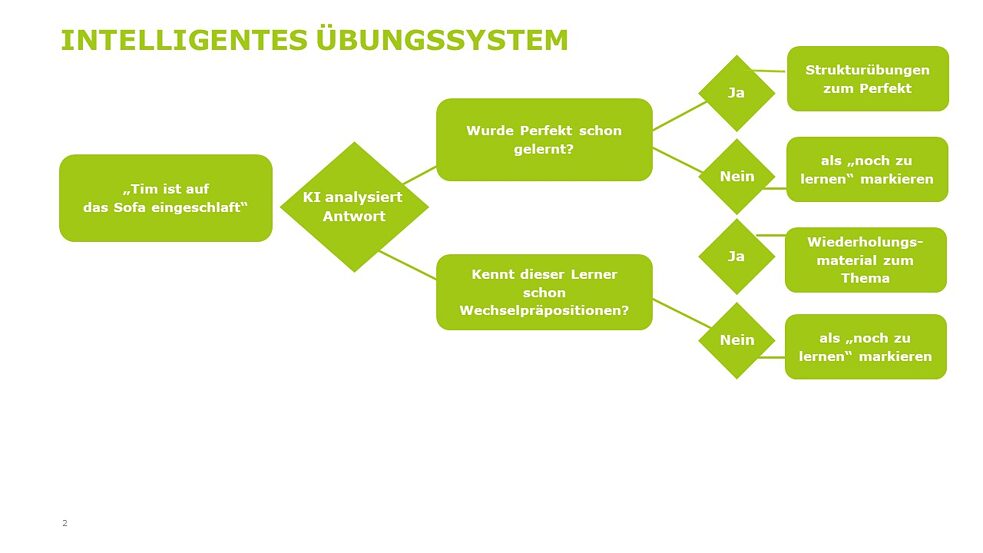

First off, it’s about constructing intelligent systems of exercises to train grammar, vocabulary and listening comprehension, for example. By analysing and processing data, these programs are designed to provide learners as well as teachers with optimized feedback on learning progress.

Secondly, it’s about developing tools to help learners translate texts, for example, or write essays themselves. Some programs even help students put together oral presentations by aiding in the creation of transparencies or improving and optimizing both the language and content of the script for a presentation.

The third area involves using media in class to provide stimulating content. Foreign-language material has become very easily accessible these days. Working suitable digital material into language classes is a way to familiarize learners with authentic discourse and speech acts.

It goes without saying that all these possibilities will massively change the teacher’s role.

Before we delve into the changes facing teachers, I’d like to talk about artificial intelligence. AI looms large nowadays, especially in computer-assisted foreign language learning. What specific kinds of AI are actually involved here and how can we benefit from these developments in our field of foreign language learning?

A number of technologies that are of particular interest for foreign language learning clearly play a big part in our everyday lives as well: namely, all the technologies that have to do with speech recognition and intelligent language processing. Extensive systems now exist that are based on large volumes of spoken- and written-word data and that use AI methods to understand and process that data. We’re all familiar with the various assistants on our smartphones that we can ask what the weather’s going to be like tomorrow or that help us write or translate texts flawlessly.

When it comes to the role of AI in language teaching, we need to ask first what a teacher’s core responsibilities and competencies are. I would stress two aspects here, though naturally there’s a whole lot more to being a good teacher: coordinating exercises and learning materials, on the one hand, and analysing learners’ performance, on the other.

What I’d expect from teachers in this context is to provide a framework and adaptive support for learning in the exercise process with effective high-quality feedback: i.e. customized, individualized support in the learning process. Based on an analysis of their current proficiency, each learner should, ideally, get precisely what they need for the next step in their development.

We’re going to be seeing a significantly wider range of intelligent tutorial systems along these lines in the near future. What’s smart about them is that they analyse individual pupils’ learning trajectories as well as their mistakes, for example. So they can predict how likely a given learner is – with their current skills as identified by the system – to successfully complete a particular task. Not only that, but the systems are capable of assessing what would be appropriate feedback for each learner.

What’s so special about these intelligent systems? Why does it make sense to assist teachers with AI methods?

Ordinarily, a teacher has twenty to thirty learners in a class and can observe their learning behaviour. The advantage of AI is that it can analyse thousands of learners across classes and whole schools. It can then determine even better, more systematically and far more rapidly which tasks are suitable for which learners and when – and which are not.

But AI can also help in selecting material that goes beyond exercises, i.e. to serve as assistants, so to speak, for teachers and textbook writers. Most of the time, to put it simply, teachers select a passage from a textbook for all the pupils to work on. But the technology enables teachers not only to find suitable texts, but also to simplify and work them up for teaching purposes, or even to generate texts entirely on their own in order to offer learners a sort of menu with linguistically suitable skill-building texts. Naturally, this would be a decisive benefit, especially in terms of individualizing the learning process.

You have shown that many programs already exist to help teachers design exciting, individualized and forward-looking language instruction. Which raises another question: Do the new technical capabilities, especially in AI, pose a threat to human teachers? What would you say to the tutor of an online language course who’s afraid of sooner or later being made redundant?

You can rest assured that those fears are wholly unfounded. We’re still going to need teachers: highly-trained foreign language experts who are competent, critical and thoughtful in handling important and interesting subject-specific content and methods. Teachers are also essential when it comes to planning lessons and providing empathic support for individual learners.

For the rest, learning technologies are going to keep making major inroads into certain areas, such as form-focused instruction, learning simple forms of written and oral communication, and using tools for the acquisition of certain language skills. That’s where I think intelligent systems can provide excellent support.

But data literacy among teachers is important here, too. It’s crucial for teachers to be familiar with the corresponding applications and capable of making competent use of these data and results. Several studies now show that the use of intelligent digital systems in a language class, e.g. when doing exercises, yields better learning results.

Doing analog exercises in class nowadays is often a matter of trial and error. Assistance programs can help teachers analyse current learning levels and plan accordingly. As teachers increasingly switch to digital training environments and use so-called “teacher dashboards” during exercise periods to process learners’ data, that will automatically keep them informed as to which learners are currently having the most difficulties, what the problems are and whether it makes sense to go on to the next planned part of the lesson or whether more reinforcement is called for before moving on.

Teachers can then target those learners in particular, explain certain things again and assign other exercises, which may be suggested by the system.

I hope teachers will be given ample support to enable them to use digital systems competently, especially for exercise periods.

The future of language learning will be blended learning: a mix of perfect-fit analog teaching with exciting contemporary content and digital exercise periods using personalized, adaptive material and all the intelligent software tools available.

I’d like to conclude our conversation by talking about our work at the Goethe-Institut. What would you recommend for us here at the Goethe-Institut? Should we develop a smart language-learning app that people can carry around with them in their pocket or handbag? Or should we strive instead to keep modernizing our existing courses, which are of high calibre in terms of content and methodology, but rather traditional in structure?

I think it would be worthwhile to gradually work new technologies into the existing courses. In any case, we should continue to base our efforts on the Goethe-Institut’s specific target group and what’s special about the Goethe courses.

It wouldn’t necessarily make much sense to start developing the best possible adaptive German grammar platform yourselves. You’d have to take a totally different approach, starting with generating huge volumes of language data.

So I’d suggest looking at how the courses are currently structured and which aspects can be improved locally using available technologies and approaches. One option would be the use of tools that specifically train speaking skills. Chatbots can help introduce learners to certain forms of communication using pre-defined scenarios.

© Colourbox

What’s more, I’d think about areas in which separate smaller-scale development would indeed make sense. For example, an AI tool with which to intelligently practise using the thousand most frequent words in the German language. Even if such programs already exist, you could collaborate on the development of a Goethe-specific app focusing on the vocabulary from Goethe-Institut courses.

© Colourbox

What’s more, I’d think about areas in which separate smaller-scale development would indeed make sense. For example, an AI tool with which to intelligently practise using the thousand most frequent words in the German language. Even if such programs already exist, you could collaborate on the development of a Goethe-specific app focusing on the vocabulary from Goethe-Institut courses.

Diagnosis and feedback are another very important function. The question here is, for example, how to employ intelligent systems to better inform learners about their own learning process as well as their progress and lacunae. Though it’s also quite useful to generate data across several different courses to identify learners’ typical mistakes and difficulties. This is a way to figure out how to design courses and feedback in future so as to yield the best possible learning results.

On the whole, I’d say: Go for it! You’re sitting on a gigantic corpus of data. If you use it together with AI methods, you’ll be able to do what you already do well even better.

Thank you very much, Mr Schmidt, for these concluding thoughts and suggestions! And thanks for the interview.

How do these developments affect the learning and teaching of foreign languages? Which AI technologies are best suited for use in foreign language learning and what are the biggest challenges involved in using them for this purpose? And what does all this mean for teachers of face-to-face and online courses?

Dr. Torben Schmidt, professor of English language didactics | Leuphana Universität Lüneburg

Torben Schmidt is a professor of English language didactics at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany. He spoke to AI specialist Moritz Dittmeyer at the Goethe-Lab Sprache (Goethe-Institut Language Lab), an interdisciplinary unit for innovation, about research in and testing of digital learning technologies.

Dr. Torben Schmidt, professor of English language didactics | Leuphana Universität Lüneburg

Torben Schmidt is a professor of English language didactics at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany. He spoke to AI specialist Moritz Dittmeyer at the Goethe-Lab Sprache (Goethe-Institut Language Lab), an interdisciplinary unit for innovation, about research in and testing of digital learning technologies.Professor Schmidt, you’re a professor of English language teaching. Given the big developments in recent years, what aspects of technology-assisted English learning and teaching can we apply to German?

The methods of teaching different foreign languages, especially English and German, are not worlds apart. We really are a big community, and all the more so insofar as there’s something very unifying about digital learning. The academic discourse is similar across different disciplines and languages.

Then again, I think we do have certain obvious advantages in English teaching: first of all, owing to the fact that there are significantly more English speakers. We also have far more professorships in linguistics and far more projects in computational linguistics.

Thanks to these factors, we researchers in English teaching have been able to make a difference in recent years, especially in computer-assisted foreign language learning.

Can you briefly explain what computer-assisted foreign language learning is?

The term “computer-assisted language learning”, or CALL for short, is nothing new; it’s been around for several decades now. Generally speaking, it’s about forms and methods of learning and teaching foreign languages. I’d break it down into three areas:

First off, it’s about constructing intelligent systems of exercises to train grammar, vocabulary and listening comprehension, for example. By analysing and processing data, these programs are designed to provide learners as well as teachers with optimized feedback on learning progress.

Secondly, it’s about developing tools to help learners translate texts, for example, or write essays themselves. Some programs even help students put together oral presentations by aiding in the creation of transparencies or improving and optimizing both the language and content of the script for a presentation.

The third area involves using media in class to provide stimulating content. Foreign-language material has become very easily accessible these days. Working suitable digital material into language classes is a way to familiarize learners with authentic discourse and speech acts.

It goes without saying that all these possibilities will massively change the teacher’s role.

Before we delve into the changes facing teachers, I’d like to talk about artificial intelligence. AI looms large nowadays, especially in computer-assisted foreign language learning. What specific kinds of AI are actually involved here and how can we benefit from these developments in our field of foreign language learning?

A number of technologies that are of particular interest for foreign language learning clearly play a big part in our everyday lives as well: namely, all the technologies that have to do with speech recognition and intelligent language processing. Extensive systems now exist that are based on large volumes of spoken- and written-word data and that use AI methods to understand and process that data. We’re all familiar with the various assistants on our smartphones that we can ask what the weather’s going to be like tomorrow or that help us write or translate texts flawlessly.

When it comes to the role of AI in language teaching, we need to ask first what a teacher’s core responsibilities and competencies are. I would stress two aspects here, though naturally there’s a whole lot more to being a good teacher: coordinating exercises and learning materials, on the one hand, and analysing learners’ performance, on the other.

What I’d expect from teachers in this context is to provide a framework and adaptive support for learning in the exercise process with effective high-quality feedback: i.e. customized, individualized support in the learning process. Based on an analysis of their current proficiency, each learner should, ideally, get precisely what they need for the next step in their development.

We’re going to be seeing a significantly wider range of intelligent tutorial systems along these lines in the near future. What’s smart about them is that they analyse individual pupils’ learning trajectories as well as their mistakes, for example. So they can predict how likely a given learner is – with their current skills as identified by the system – to successfully complete a particular task. Not only that, but the systems are capable of assessing what would be appropriate feedback for each learner.

What’s so special about these intelligent systems? Why does it make sense to assist teachers with AI methods?

Ordinarily, a teacher has twenty to thirty learners in a class and can observe their learning behaviour. The advantage of AI is that it can analyse thousands of learners across classes and whole schools. It can then determine even better, more systematically and far more rapidly which tasks are suitable for which learners and when – and which are not.

But AI can also help in selecting material that goes beyond exercises, i.e. to serve as assistants, so to speak, for teachers and textbook writers. Most of the time, to put it simply, teachers select a passage from a textbook for all the pupils to work on. But the technology enables teachers not only to find suitable texts, but also to simplify and work them up for teaching purposes, or even to generate texts entirely on their own in order to offer learners a sort of menu with linguistically suitable skill-building texts. Naturally, this would be a decisive benefit, especially in terms of individualizing the learning process.

You have shown that many programs already exist to help teachers design exciting, individualized and forward-looking language instruction. Which raises another question: Do the new technical capabilities, especially in AI, pose a threat to human teachers? What would you say to the tutor of an online language course who’s afraid of sooner or later being made redundant?

You can rest assured that those fears are wholly unfounded. We’re still going to need teachers: highly-trained foreign language experts who are competent, critical and thoughtful in handling important and interesting subject-specific content and methods. Teachers are also essential when it comes to planning lessons and providing empathic support for individual learners.

For the rest, learning technologies are going to keep making major inroads into certain areas, such as form-focused instruction, learning simple forms of written and oral communication, and using tools for the acquisition of certain language skills. That’s where I think intelligent systems can provide excellent support.

But data literacy among teachers is important here, too. It’s crucial for teachers to be familiar with the corresponding applications and capable of making competent use of these data and results. Several studies now show that the use of intelligent digital systems in a language class, e.g. when doing exercises, yields better learning results.

Doing analog exercises in class nowadays is often a matter of trial and error. Assistance programs can help teachers analyse current learning levels and plan accordingly. As teachers increasingly switch to digital training environments and use so-called “teacher dashboards” during exercise periods to process learners’ data, that will automatically keep them informed as to which learners are currently having the most difficulties, what the problems are and whether it makes sense to go on to the next planned part of the lesson or whether more reinforcement is called for before moving on.

Teachers can then target those learners in particular, explain certain things again and assign other exercises, which may be suggested by the system.

I hope teachers will be given ample support to enable them to use digital systems competently, especially for exercise periods.

The future of language learning will be blended learning: a mix of perfect-fit analog teaching with exciting contemporary content and digital exercise periods using personalized, adaptive material and all the intelligent software tools available.

I’d like to conclude our conversation by talking about our work at the Goethe-Institut. What would you recommend for us here at the Goethe-Institut? Should we develop a smart language-learning app that people can carry around with them in their pocket or handbag? Or should we strive instead to keep modernizing our existing courses, which are of high calibre in terms of content and methodology, but rather traditional in structure?

I think it would be worthwhile to gradually work new technologies into the existing courses. In any case, we should continue to base our efforts on the Goethe-Institut’s specific target group and what’s special about the Goethe courses.

It wouldn’t necessarily make much sense to start developing the best possible adaptive German grammar platform yourselves. You’d have to take a totally different approach, starting with generating huge volumes of language data.

So I’d suggest looking at how the courses are currently structured and which aspects can be improved locally using available technologies and approaches. One option would be the use of tools that specifically train speaking skills. Chatbots can help introduce learners to certain forms of communication using pre-defined scenarios.

Diagnosis and feedback are another very important function. The question here is, for example, how to employ intelligent systems to better inform learners about their own learning process as well as their progress and lacunae. Though it’s also quite useful to generate data across several different courses to identify learners’ typical mistakes and difficulties. This is a way to figure out how to design courses and feedback in future so as to yield the best possible learning results.

On the whole, I’d say: Go for it! You’re sitting on a gigantic corpus of data. If you use it together with AI methods, you’ll be able to do what you already do well even better.

Thank you very much, Mr Schmidt, for these concluding thoughts and suggestions! And thanks for the interview.