Openings in Eastern Europe

- 1988Budapest (Hungary)

- 1989Sofia (Bulgaria)

- 1990Prague (Czech Republic)

- 1990Warsaw (Poland)

- 1991Krakau (Poland)

- 1992Moscow (Russia)

- 1993Minsk (Belarus)

- 1993St. Petersburg (Russia)

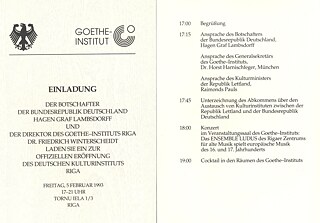

- 1993Riga (Latvia)

- 1993Bratislava (Slovakia)

- 1994Kiev (Ukraine)

- 1994Tbilisi (Georgia)

- 1994Almaty (Kazakhstan)

-

© Goethe-Institut Archiv

-

© Goethe-Institut Archiv

-

Photo: Goethe-Institut Archiv

-

© Goethe-Institut Archiv

Photo: Bernhard Ludewig

1990

The Goethe-Institut Prague opens

“A recording device was present whenever the ambassador received his guests.”

Learn more

1990

The Goethe-Institut Prague opens

“A recording device was present whenever the ambassador received his guests.”

The fall of the Iron Curtain not only leads to new Goethe-Institut locations in Central and Eastern Europe; it also exposes curious goings-on from daily life during the Cold War. In Czech Prague, the Goethe-Institut takes over the empty GDR embassy and finds more than just abandoned furniture.

The locations proposed for the new institute are not all that appealing: they are either too far outside the city or too loud. So Carola Bloss, wife of soon-to-be institute director Jochen Bloss, suggests an alternative: “The GDR embassy was just standing there empty and the rent had been paid through December 31st by the GDR,” Jochen Bloss recalls. The caretaker gives him the keys, and the rooms are still completely furnished when they move in on October 4. Dishes, stationary, even the plastic rose on the ambassador’s desk are all still in place. A cleaner hands it to Carola Bloss with the words: “It was always with the ambassador, so I can give it to you.” The couple later spies a small, black dot among the petals, which turns out to be a bug. “That means,” Jochen Bloss says, “a recording device was always present whenever the ambassador received his guests at the round table.” He has saved the bugged plastic rose to this day.

Photo: Bernhard Ludewig

1991

President endows Klaus von Bismarck Prize

For the unseen heroes

The Goethe-Institut is active worldwide with many locations, so unpredictable situations arise from time to time. Then on-site staff need to step in, take responsibility and try creative approaches. The Klaus von Bismarck Prize has honoured such extraordinary efforts since 1991.

Narayan Muhuri, a guard at the Goethe-Institut in Kolkata, spends a total of 85 days, just under three months, alone in the institute building in spring 2020. Instead of isolating with his family during the coronavirus lockdown, he keeps the server room and air conditioning up and running. When cyclone Amphan sweeps through the city in May, he prevents damage to the building. Leela Chinoy assists him in maintaining the building’s safety. Head of Administration since 2020, she has worked at the institute since 1980 with a six-year break. Both receive the 2020 Klaus von Bismarck Prize for their outstanding dedication. Endowed in 1991 by the Goethe-Institut’s fifth president, the annual award goes to two staff members in recognition of “many years of notable service in promoting the Goethe-Insitut’s mission or extraordinary dedication in exceptional circumstances.”

Photo: Bernhard Ludewig

1992

The Goethe-Institut Moscow opens

“Ms Dittrich, you have to set up Moscow.”

Photo: Bernhard Ludewig

1995

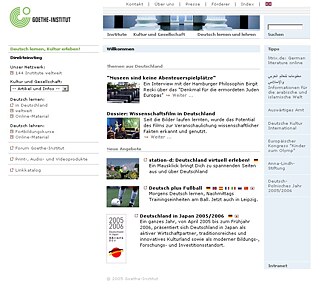

Now also an online network

The www.goethe.de website goes online

The internet is still in its infancy in the mid-1990s, but the Goethe-Institut is already online by 1995 – two years before search engine Google. Soon the digital world is an integral part of the institute’s activities: During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, events and language courses are moved almost entirely online.

-

The first Goethe-Institut website goes live in 1995. Photo: Goethe-Institut -

The website’s look has dramatically changed just two years later. Foto: Goethe-Institut -

Football, the German language, and German films: the 2002 homepage. Photo: Goethe-Institut -

The tenth anniversary of www.goethe.de: the 2005 homepage. Foto: Goethe-Institut -

An interview with British writer John le Carré and “Scenes from 60 years of the Goethe-Institut” on the site in 2011. Foto: Goethe-Institut -

What the www.goethe.de homepage looks like today. Foto: Goethe-Institut

Photo: Thomas Robbin / picture alliance / imageBROKER

© Goethe-Institut