Interview with the activist Athambile Masola

“Fallen out of history”

Together with the Asinakuthula Collective, Athambile Masola tells the stories of black African women that have not been in history books or Wikipedia so far. After an edit-a-thon as part of the project “Decolonise The Internet”, she spoke with “The latest” at Goethe about her work.

By Sören Jonsson

What does the Asinakuthula Collective do and what is your role within the organization?

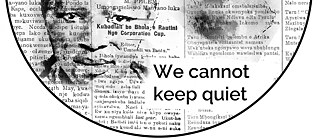

I am the founder of the Asinakuthula Collective, which is structurally an NPC (non-profit company). We’re a group of teachers and researchers who are interested in the narratives of black women in particular, who have been pretty much left out of history. If you take a look at our logo, it is a picture of Nontsizi Mgqwetho and Charlotte Maxeke and behind them you have newsprint. Those are the newsprints of the actual articles that they wrote in the newspapers in the 1920s, but many people don’t know about them.

The collective’s name derives from a line in Nontsizi Mgqwetho’s poetry: “Asinakuthula umhlaba ubolile” – „We cannot keep quiet while the world is in shambles.“ Nontsizi Mgqwetho was a Xhosa writer in the 1920s public space. She was also a performance artist, because she used to perform at public events. These women are emblematic for our vision, because even while their work had made an impression on their contemporaries, they are hardly recognized. We want to use them as a starting point to really think about how you build an institution around these women’s names and women’s lives and to say: How do we get them into history books? How do we get them into the internet? How do we get them to become general knowledge?

When did you start working on this topic?

It seems like I keep finding these women by mistake, if there is such a thing. It’s almost serendipitous in the way that I’m led to artifacts that allow me to ask questions about these women. The first one I became quite obsessed with is Noni Jabavu. She was a South African writer during the 60s and she lived all over the world. She was a pioneer, really. Her memoirs were initially published in the 1960s and there was another small run of them in the 1980s but otherwise they’ve fallen out of print. They’re not really available anywhere. I came across them in an antique book store and they immediately stood out to me so much, I decided to do my PHD project on them. I was going to look on her work from a literary perspective.

But the more I delved into her, I found myself looking at old newspapers like The Bantu World from the 1930s for example. It was one of the prominent newspapers in the 1930s that was featuring the lives of not only black people in general but they had a women’s page specifically, which was very unique at the time. Just by browsing through the 1935 edition, I found so many articles about and by black women who were doing fantastic things around that time, so for example I found a letter by Frieda Matthews who was visiting London and was writing a letter to her readers about her experience. I found an article by a women called Rilda Marta who had gone to the US to be a beautician and she wrote a three-part letter to her readers in The Bantu World about her experiences abroad. I found a speech that had been made by a woman called Ellen Pumla Ngozwana which was titled “The Emancipation of Women” that she had done at Inanda seminary in 1935. So here’s one edition, just one year of one publication that had given me so much evidence.

For me the question was then: Well, when we go back to these archives what are the choices that we’re making? What do we see and what do we not see? Because the evidence is there. Is this because the research that we put into these resources deliberately chooses to leave this out or because it doesn’t fit into their narrative of what it means to be a black women during this time?

It made me realise: If people like me won’t construct history, people like me will fall out of history. That’s what happened to these women: They were making historically significant things, but then they weren’t shaping the construct of what ends up in the history books. It’s up to researchers like me and the collective I work with to do that. Half of the work is actually quite easy, because all the evidence is there. The other half is to change the deliberations of who to put in the history books and through that change the construct of history at large.

What is the relationship between these two tasks and what challenges do you see in these two phases of your work?

I see it as quite interrelated and iterative. One of the things is that you find this information, but then what do you do with it? Do you simply digitalise it and leave it online and hope that people will find it? That was part of what I was doing as a researcher with my PHD and the research around it.

It actually needs to be a three part job: First, it’s archival work, then it’s the work of introducing this data to the public by either writing about it or producing other media about it – it’s a kind of lobby work for recognition. The final step is that other people step in and do research of their own.

The challenges are plenty, but all have to do with capacity in one way or another. The capacity of researchers past an Honours degree, the capacity for translation when the source material isn’t in English, and of course the capacity for resources. Following that there might also be the question of literacy. All of these aspects really overlap and that’s why it was so great for us to find the project that the Goethe-Institut is doing and the way you went about it with the edit-a-thon. Despite it being so ubiquitous, I didn’t ever think of Wikipedia as something that anyone can change or add to.

Could you talk a little about the articles you worked on during the edit-a-thon?

One of the articles that we worked on was for Nomhlangano Beauty Mkhize – a person that didn’t exist before, as far as Wikipedia was concerned – except for one or two articles, the whole internet really. It was quite fascinating for us to see the process of having gathered the information and then working on the article and within three hours this person who was invisible before could be easily found. It happened that quickly!

It’s encouraging that traction can be built like that, because for basic representation it is important that something comes up when you type someone’s name in a search engine.