German-Israeli Literature Days 2018

Parting from the Ideals of our Parents

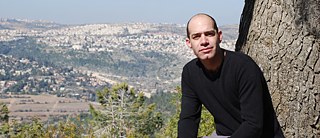

What is just? Israeli author Yiftach Ashkenazy observes the transformation of the Israeli identity into which he was born. He is a guest at the German-Israeli Literature Days organised by the Goethe-Institut together with the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Many members of my parents’ generation, who still spoke of the good, innocent times, attained increasing prosperity, touting explanations as to why it was logical that there were rich and poor. Maybe I just had dealings with many people who grew up in a different reality than I did when the saying, “We are all Israelis,” swept the disparity and injustice that existed in Israeli society under the rug.

To this day, there is an undeniable gap between the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi in Israel, between long-established residents and new immigrants, between Jews and Arabs. Through these insights, I distanced myself from the identity into which I had been born. I understood that the ideals that my parents believed in were sometimes naive, or at other times purported naiveté, so that they allowed extremely severe things to happen in front of all our eyes.

In a certain sense, the process I experienced, which distanced me from my parents’ identity, reflects a profound process that went on throughout Israeli society. Dramatic political change began in 1977 with the seizure of power by the right wing. From that moment on, the elite I was born into began to lose its influence, and the Israeli, Zionist, leftist and socialist identities that had shaped me were worn down. The criticism that came up with regard to that identity (expressed by the religious right) was only slightly different from mine, but the principle was essentially the same. Most saw in this identity, which wanted to be Israeli, a hypocrisy that distanced many from their tradition and additionally allowed for a great deal of injustice.

A question of identity

In recent years, this distance from the pan-Israeli, socialist, Zionist identity has reached its peak. Many politicians poured oil into the fire. Prime Minister Netanyahu always fed his power by generating friction between different social groups. These politicians exploit the rage that is genuine and even justified to drive a wedge between the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, the centre and periphery, secular and religious, new immigrants and long-established, rich and poor, Arab residents and Jewish majority. Regrettably, in Israeli society today there is only one common identity in the united hatred of another group, such as the Arabs or the labour immigrants who fled Africa to Israel.However, in recent years, parallel to my criticisms, I have gone through a process that has slightly changed my attitude to the identity I was born into. This criticism is in the context of my last book, Auf zur Verwirklichung (To Realization). It deals with my father, of blessed memory, his comrades, and the process they went through in their lives. Their story began as that of a group of idealistic young people who believed in both Zionism and in political and economic justice, reflecting the process the country was undergoing.

The belief in justice

If I could succeed in describing this process, I felt that I would also be able to gain some understanding. After all, they belonged to the left but they had nevertheless done their military service in the occupied territories and were part of something that ruled over another people. They were the ones who began as socialists, then gave up their belief in it and became part of the capitalist game.The work on the novel set something in motion for me. I realised that although I criticised these people who were responsible for many of the bad things that had happened in the country I loved and cherished them. They had made a lot of mistakes and their value system turned out to be quite problematic, but in the end their belief contained something very significant. They believed that Israel could represent something new and good, they believed in a just and moral state. They also believed that the Israeli identity could open the door to something new and good. This insight did not cause me to stop criticising, but alongside that I developed a love for the identity that shaped me.

In spite of everything, there was something good about the Israeli, secular, socialist identity into which I was born. It may have been naive, but it believed in social justice, and being Israeli meant being part of something right and just. These days, when this unity and belief in the good seem so far away, this identity awakens a tinge of yearning in me.