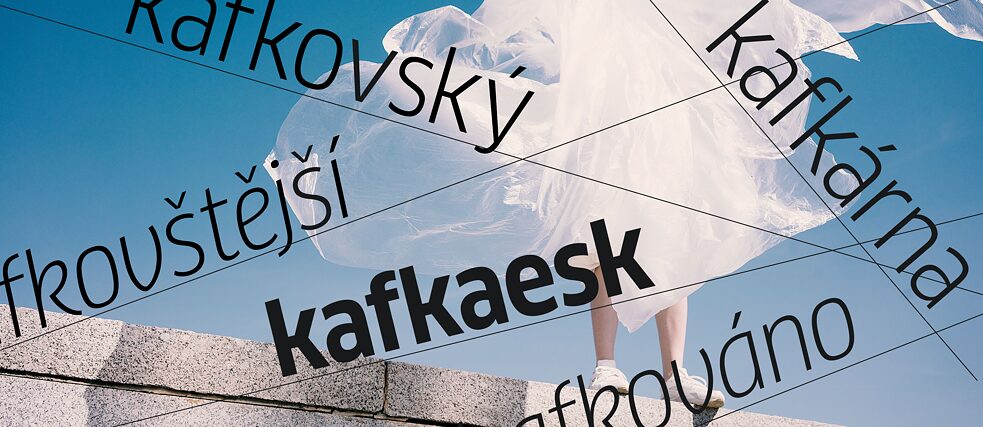

Kafkaesque

Kafka’s traces in the Czech language

Almost everyone knows the word “Kafkaesque”. In Czech, there is a whole range of other Kafka vocabulary – such as “not enough of Kafka”.

By Tomáš Moravec

If we look in the Duden, the standard rulebook for German spelling, we find the charming term kafkaesk under the letter “k”. This word, we learn, should be understood in the sense of “threatening in an incomprehensible way”, and the dictionary also adds that it is derived from the name of the Austrian writer Franz Kafka (1883–1924).

Leaving aside the label “Austrian” (about which many might certainly have reservations), let us in particular note that the word kafkaesk is indeed to be found in the Duden, and, by extension, Franz Kafka’s enormous influence on the German language. This is certainly a great tribute: after all, words such as goethesk or schillersk don’t exist in German. In addition, you will also find similar Kafka-derived words in other languages: kafkaesque in English, kafkaïen in French, kafkowski in Polish and, even in Swedish, there is kafkaartad.

However, the Prague writer’s influence in terms of newly coined words has been most profound in the Czech language. Mostly these are colloquial expressions and puns allowed for by Czech grammar. Among them, the expression kafkárna is of note, having penetrated very far, with many native Czech speakers using it almost on a daily basis (and not just when dealing with bureaucratic absurdity). As you correctly guessed, kafkárna (unlike kafkaesk) is a noun. Its gender is feminine and it refers to an absurd situation, or an institution with an overwrought bureaucracy, in which one can feel like one is in a madhouse.

“What a kafkárna,” is what a lady might say, when she is sent from one desk to another at the employment office. “You can’t even imagine this kafkárna,” a friend might say to another friend to describe the crazy situation at his workplace. By the way, the Czech language also knows the word švejkárna denoting a situation of ridiculing the authorities or shirking one’s duties. Sounds like an allusion to Josef Švejk, a literary character from Jaroslav Hašek’s books, right? That’s because it is.

But back to Kafka: When there is sometimes too much of Franz Kafka somewhere (which can happen, for example, in Prague souvenir shops), it can be said that the place is překafkováno (overflowing with Kafka). If, on the other hand, there is not enough of Franz Kafka, we can say that it is nedokafkováno or podkafkováno. You won’t find any of those words in the dictionary of standard Czech, but the locals will understand where your shoe pinches.

Of course, there’s also a Czech version of the adjective kafkaesque. It translates as kafkovský and can be inflected (kafkovský, kafkovská, kafkovské, kafkovští, kafkovským, kafkovskými ... and so on) and graded: kafkovštější (more kafkaesque) and nejkafkovštější (most kafkaesque).

A kafkaesque situation might also sometimes be described by Czechs as kafkovitý (again inflectable and gradable in a hundred ways) instead of kafkovský, meaning existential, absurd, but also gloomy – the way Kafka’s works are seen by Czechs. However, never forget that, as we say in Czech, “for every sweet cherry there’s a sour one”, that is that there are as many different understandings of Kafka’s work as there are readers. That’s why deciding whether something is kafkovské or kafkovité can sometimes amount to a crazy kafkárna.