Berlin’s housing market

Airbnb – a Blessing or a Curse?

Is the online Airbnb flat sharing platform making Berlin’s housing shortage worse? Three students analysed the data to help answer this question. And reached some surprising conclusions.

By Maike Brzoska

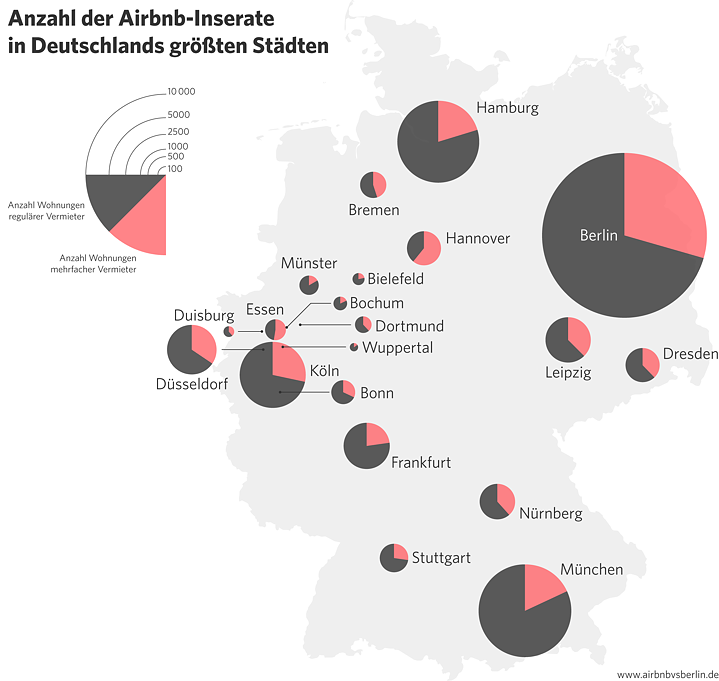

In Berlin rents have risen faster than in almost any other German city in recent years. The capital was once known for its low rents, but today affordable living space is increasingly hard to find. On the other side of this equation, a place to stay on a visit to Berlin is amazingly easy to find. The Airbnb flat-sharing platform alone offers over 10,000 accommodation units for rent every day, most of them whole flats.

This has kicked off heated debate and even a new law passed in 2014. Airbnb, the argument goes, was originally intended for private people looking to rent out their flat or room for a short time, but now increasingly features purely commercial holiday flats. Many Berlin residents have discovered it is worth holding on to a flat even long after they’ve moved out to sublet it as a pricy holiday getaway. Landlords can also generate more income if they let their apartments to holidaymakers short-term than to regular tenants. The latter is generally assumed to be a major driving factor behind the housing shortage. But is it really?

In the midst of the heated debate on the rights of sharing economy platforms, three design students from the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam decided to use data analysis to take a closer look at Airbnb’s real impact on the rental market. They were particularly interested in identifying how many users offer more than one flat for rent, a likely indication that the flats are not private living spaces. Alsino Skowronnek, one of the three project managers, explained their findings in an interview.

Your “Airbnb vs Berlin” data project made some headlines. Did Airbnb ever contact you?

Yes, actually, they go in touch in 2015, shortly after we first released our results. Airbnb wrote us an email to ask where we had gotten the data. We were all a bit puzzled.

And did they make any waves?

No, they made us a job offer. They invited us to their Berlin office and wanted to know more about our project. I think they were actually kind of impressed, even if Airbnb has a different take on the data than we do. We only used publicly accessible data: We sorted the variety of rooms and apartments available on Airbnb at that time via an API interface. We never considered taking the job, though. The three of us – Jonas Parnow, Lucas Vogel and I – were studying at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam at the time, in 2015.

You designed your Airbnb project for a course on data visualization and digital storytelling. Why did you choose that topic?

At the time, debate on whether Airbnb was good or bad for cities was just kicking off in Germany. People were especially interesting in finding out whether such platforms were making the housing shortage worse or driving up rents.

A discussion that continues to this day.

It was kind of personal for me at the time because I was looking for a flat. I couldn’t find anything in the Wranglekiez in Kreuzberg were I was living and wanted to stay. Then someone said I should rent out an Airbnb flat. I was very surprised to see how many places were available on Airbnb, especially in the more popular neighbourhoods, when there was hardly anything on the normal housing market. That got me interested in how big Airbnb is in Berlin.

You analysed the rooms and flats available on Airbnb. What did you find out?

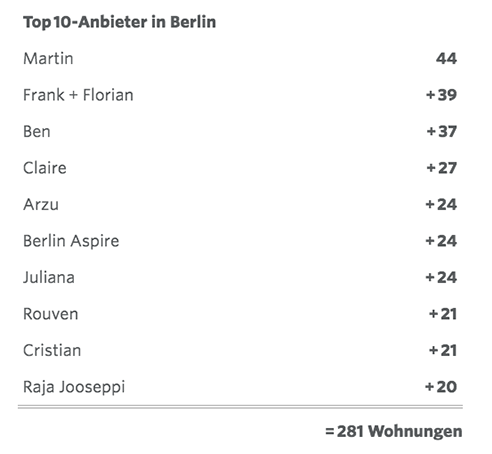

We looked at the average price range, for example, where in the city flats and rooms were available, and how many advertisements each user placed. I found it really interesting that the data did not support Airbnb’s image. They advertise the idea that you can spend your holiday with friends – as if it were a very private exchange. But we were able to show that a huge number of commercial landlords were active on the platform. Some of them had posted more than 30 or 40 apartments on Airbnb. This has nothing to do with a student who occasionally sublets their room when they go on vacation.

Some commercial landlords post more than 30 or 40 apartments on Airbnb. | Photo: © Airbnbvsberlin

That's why we also looked at the data over time. It was interesting to note that the number of Airbnb rentals continued to rise steadily in 2015. It then dropped again rapidly a few months before May 2016. In a fairly short time window, the number of flats and rooms on Airbnb dropped by 40 percent in Berlin.

So the law is working?

In the short term, yes. But in the months that followed, we saw a renewed uptick. This may be because the media reported that the city was completely overwhelmed in its attempts to identify illegal rentals. And parts of the law were classified as unconstitutional, and then amended. If you ask me though, the law still needs some tweaking, as it does not really distinguish between commercial landlords and people who sublet from time to time when they go on holiday. The commercial landlords are the real problem for the city, since they are depriving the rental market of housing.

So what is your takeaway from the results?

When I was looking for an apartment, I felt like Airbnb was huge in Berlin. But that’s not true everywhere, though it does have a big impact in a few specific neighbourhoods in Kreuzberg, Mitte, Neukölln and Prenzlauer Berg. Our data also showed that the Airbnb hype was concentrated in a few hotspots in the city. Only 0.4 percent of all the flats in all of Berlin are being rented out via Airbnb.

0.4 percent does not sound like much at first, but in absolute figures Airbnb features a really impressive number of flats, especially in the more sought-after downtown districts. So would you say that Airbnb is making the housing shortage in Berlin worse?

I think there are many factors contributing to housing shortages and rising rents. In my opinion, Airbnb is not solely to blame. I would characterise Airbnb as a catalyst for changes already taking place in some neighbourhoods. Look at Wrangelkiez for example: In the past, the area was more mixed with more green greengrocers and small shops. Today the big cafés that serve the tourist market are taking over, which falls under gentrification or touristification. I think Airbnb is accelerating such changes.

Berlin is the city with most Airbnb offers in Germany. (Orange: Apartments of people renting out one flat. / Black: Apartments of landlords posting more than one apartment.) | Foto: © Airbnbvsberlin

Airbnb vs. Berlin

The “Airbnb vs. Berlin” project was the brainchild of design students Alsino Skowronnek, Lucas Vogel and Jonas Parnow during a data journalism course at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam. To identify the Airbnb rental platform’s impact on the housing shortage in Berlin, they evaluated the website’s publically accessible data and published their results on the airbnbvsberlin.de website in texts, diagrams and informational graphics. In addition to providing information about the number of Airbnb apartments in Berlin, their location and prices, the website also shows how many Airbnb users post multiple apartments at the same time. The project was nominated for the "Grimme Online Award" in 2016 based on the following rational: “Are portals like Airbnb contributing to the housing shortage in Berlin and driving up rents? This debate is ongoing among residents and politicians alike. The “Airbnb vs. Berlin” website offers solid journalistic data to inform this conversation.”

Comments

Comment