August Sander

Staging of the German past

On the 50th anniversary of the death of the photographer August Sander (1876-1964) in 2014, three exhibitions, in Cologne, Bonn and Munich, commemorated his portrait cycle “People of the Twentieth Century” – a major artistic project whose photographs of farmers, artisans, soldiers, politicians and artists afford a look at German society at the time of the Weimar Republic.

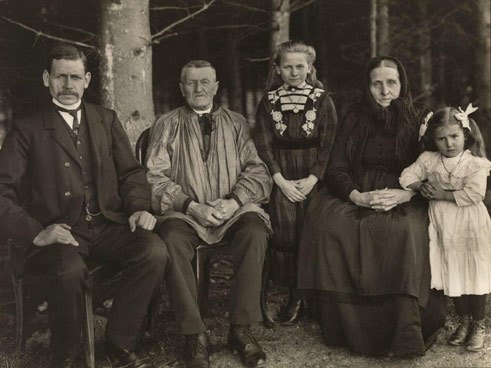

Three young farmers from the Westerwald stop briefly on their way into the town so as to turn to the eye of the observer, who captures forever this everyday moment from 1914. A farmer’s family sit demurely on chairs in front of the Rhine; the river defines the background of the image and so too the origin of the family. A pastry chef wearing a white smock pauses in his stirring for a moment; confidently, he fixes his eyes on the photographer. A jobless person, looking lost, leans against a house wall, slouching in a much too large coat. A tenor holds a wool scarf with his delicate hand to protect his voice. There follow portraits of a police constable, a pilot, a solider, a handyman, a theologian, an artist.

Sander’s goal was that these photographs should afford a comprehensive portrait of German society in a clearly defined historical period. For Sander, a pioneer of the New Objectivity, photography was above all a medium for the representation and realistic rendering of selected subjects, behind which the author-photographer should disappear. To this end, Sander chose a chronology that bolstered the documentary character of the pictures: the portraits are divided into seven individual volumes – The Farmer, The Craftsman, Woman, The Estates, The Artist, The Big City and The Last Men (invalids, disabled, the blind).

Between individuality and social representation

The people that look out of the pictures are defined by their social affiliation: by the professions they practice, or by the “estate” to which they belong. Cited with each portrait is the place and date of the photograph, but not the name of the person, except in special cases where he had attained a certain degree of social prominence. Thus the photographed people are shown in the tension between individuality and social representation. In the series of photographic folders, the weather-beaten face of a farmer merges with all the other farmer portraits into the visage of the farmer as exemplar of “man close to the earth”, as Sander calls him. As embodied history, the “estate” has been stamped deep into the physiognomy. The “habitus”, which the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu saw as the internalization and incarnation of structurally determined class-specific boundaries, is not restricted to clothing and taste, but also defines the body posture and demeanour of a person. This is particularly evident in the portraits of the young farmers from the Westerwald, who, though photographed walking in their Sunday-best, are no less recognizable as young farmers, or of the brooding theologian, the self-assertive banker or the petrified family of a politician. Slideshow: August Sander

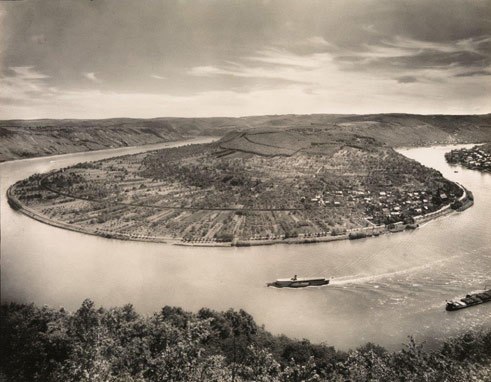

August Sander, The Rhine at Boppard, Osterspey, 1938, Collection Lothar Schirmer, Munich | © Die Photographische Sammlung /SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Slideshow: August Sander

August Sander, The Rhine at Boppard, Osterspey, 1938, Collection Lothar Schirmer, Munich | © Die Photographische Sammlung /SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014