Georgian-Abkhaz relations and “Protracted Conflict Syndrome"

This article was produced in the framework of the "Unprejudiced" project with the support of the Eastern Partnership Programme and the German Federal Foreign Office in autumn 2022.

Author: Ana Kikaleishvili

30 years have passed since the beginning of the armed conflicts in Georgia. Neither side involved in the conflict has achieved its goal. However, the collateral damage created by this conflict still has a painful effect on both parties. Currently, 264,015 people are classified as internally displaced persons (IDPs), according to the Ecomigrants and Livelihood Agency of Georgia. Ethnic Abkhaz people, who make up little more than 100,000 of the entity's population, are concerned about becoming overly dependent on Moscow on an economic, political, and cultural level or, in other words, about being assimilated. The international status of Abkhazia is still up in the air. There is no likelihood of any EU member state or any significant international recognition in the immediate future, and just three nations—Russia included—consider it independent from Georgia. Disagreements have molded contemporary perspectives on the exercise of authority affecting demography, language, access to resources, and political representation. 30 years is more than enough time to reflect on the past and consider whether the current scenario needs to change.

Ilona and Liana represent different generations (the names have been changed at their request - for their safety and that of their family members). Both were born in Abkhazia, although Ilona was born there after the war - she is in her late 20s, whilst Liana was already married to a Mingrelian man and resided in Mingrelia at the time of the war. These two people have distinct perspectives on the relationship between Abkhazians and Georgians. It's worth noting that one of their parents is Mingrelian, which is not uncommon in Abkhazia. Mingrelians are a sub-ethnic group of Georgians, who speak the Mingrelian language. Apart from Mingrelian, almost all Mingrelians speak their national language - Georgian.

Abkhaz and Mingrelians were intertwined, Liana recalls. My mum was Abkhazian and my dad was Mingrelian. I went to an Abkhazian school but my dad wanted us to speak Mingrelian at home.

Among ordinary folks, such as Georgians and Abkhazians, there was still a lot of closeness, as indicated by the number of mixed marriages that the Abkhazians had most with Georgians in multi-ethnic Abkhazia, states Giorgi Anchabadze, a Georgian historian of Abkhaz heritage.

Abkhazians do not regard Mingrelians as Georgians and would like to see them as a non-hostile nation, whilst Georgians say they are Georgians, says George Hewitt, the Caucasian languages expert. Community leaders in Gali (the administrative unit of Abkhazia, which has a majority-Georgian (Mingrelian) population (98.21% of the total population as of the 2011 census)) also, it seems, prefer to be called ‘Georgians’, which hardly serves their interests inside Abkhazia.

During the war, several of my family members fled to Mingrelia, Liana says. They didn't like the political climate in Abkhazia, where you had to accept it to stay. They didn't, so they left. My parents and one of my brothers stayed. They identified as Abkhazian. My father even had to declare that he considered one of his sons lost since he sided with the Georgians. People are for themselves, you know. He was trying to save his family and ensure their safety.

Liana faced the most harrowing wartime experiences. This was the period in her family's history when they had to fight for their "politics." One of my brothers fought on the Georgian side, and the other one fought on the Abkhaz side. There was no other option. After the war, my mother couldn't even stand Georgians, and Abkhazians turned into radicals who didn't want Mingrelians.

Enguri Bridge, separating Abkhazia from Georgia.

Abkhazian and Georgian nationalism in conflict

I’m Abkhazian and proud of it, says Ilona. We have our language, our own history. It surely belongs to Georgia too but we want to be independent. I understand many people lost their houses but we are independent now. What’s the problem between Georgia and Abkhazia is that Georgians never want to accept this - we are now different. Maybe we'll have a relationship after you realize this.

Post-war Abkhazia found itself in uncertainty, recalls Guram Gumba, a historian and politician from Abkhazia. It seems that the preservation of ethnic integrity and cultural identity is the main motivation that stimulates Abkhazians to build an independent state.

Abkhazian nationalism is conflicting with the Georgian national project due to its ethnic origin. According to Gia Nodia, a Georgian political analyst, there are at least two varieties of nationalism in Georgia. There is political, civil, pro-Western nationalism, the primary goal of which is independence and sovereignty. It sees Russia as the main source of threat. However, there is another type of nationalism, more ethnocultural in nature, that is concerned with the preservation of cultural identity.

They remember those who died in the war, as we do, says Liana, while neither side is aware of the other's losses. The population lives with memories of the war.

As a result, when historical events are considered, Georgian ties are either demonized or ignored. On the other hand, the Georgian discourse romanticizes Abkhazians and South Ossetians as "brothers and sisters" while demonizing them as "ungrateful" and "proxies," as stated in the CARNEGIE EUROPE project "The Future of Georgia." While Tbilisi emphasizes the influence of Russian occupation forces and their de facto political control, which are illegally stationed in both territories, Abkhazians and Ossetians portray Russian military units stationed in the Sukhumi and Tskhinvali regions as a guarantee of their own security.

If we rightfully have the feeling that we are victims of Russian aggression and are looking for solidarity, what should we do with the sincere feeling of the Abkhazians? Will it disappear by itself? states Paata Zakareishvili, a Georgian political scientist.

In addition to Georgia's and the world's positions, according to Zakareishvili, there are other factors that prevent the full realization of the Abkhazian project: a) Russia's geopolitical interests on the Black Sea, which imply total control of Abkhazia and exclude its true sovereignty; b) Different Abkhazian ethnic groups' differing perspectives on the project. The majority of ethnic Abkhazians have established the objective of gaining universally recognized independence. Ethnic Russians and Armenians residing in Abkhazia are unable to envision their security and well-being without coexistence with Russia, just as remaining Georgians in the territory are unable to imagine their future without Georgia.

According to a 2016 survey by the Czech news agency "Medium Orient," approximately half of the population of Abkhazia (45.2%) favors the republic's independence being maintained, while a third favors joining Russia.

Window to the world through Russia

Russia's presence in Abkhazia is invisible, explains Abkhazian historian Guram Gumba, though pervasive in domestic politics, not to mention foreign policy. Any political decision in Abkhazia is considered through the prism of Russian interests.

Many Abkhazians justify the Russians in the Russia-Ukraine war, Liana claims. They don't know what is happening. My sister, who lives in Abkhazia, also believes so. I tell her over the phone, to listen to what is happening in Ukraine. Everything is a lie, she says. I can't prove anything, they don't show what we see, and I don't want to lose my sister over this argument.

Only via Russia do we have access to the outside world, Gumba says. This presents Russia with the chance to pursue its own policy in Abkhazia using the vast array of influence tactics and technologies at its disposal.

Since Russia is Abkhazia's primary resource supplier, this undoubtedly has some influence on the current policy. According to Gumba, policies are frequently carried out against national interest or consensus and instead in accordance with the demands and expectations of Russian economic and financial institutions.

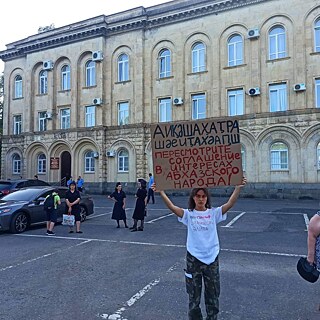

In September, Abkhazian youth group organized a peaceful procession with elements of a demonstration opposing the transfer of ownership of the Pitsunda state dacha. In January 2022, per a secret agreement that was reached between the Abkhazian and Russian authorities, the government country residence "Pitsunda" will be transferred to the ownership of the Russian Federation. In a press release, the initiative group stated that the only source of power in Abkhazia is its people, and they urged legal representatives to make important decisions in the best interests of the Abkhaz people.

The spike in flight rates has exacerbated the challenges caused by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Land transportation through Georgia is the most convenient and cost-effective way for Abkhazians to connect with the Abkhazian diaspora in Turkey. This is one of the reasons they are considering eliminating the bans at the Enguri checkpoint.

Tengiz Dzhopua, a public figure in Abkhazia, believes that politics and the economy should be kept separate wherever possible. We are forced, if not compelled, to use whatever way to increase our interaction with the outside world. We are in a very difficult economic situation. We need to find additional opportunities to develop the domestic market.

“Protracted Conflict Syndrome”

According to CARNEGIE EUROPE's initiative "Future of Georgia," radical narratives produce societal uncertainty and mistrust in the peace-building process. Absence of critical analysis and reflection on dominant narratives reduces chances of success. Meanwhile, stereotypes hold both Georgian and Abkhazian societies trapped: an environment is created where any Georgian who attempts to challenge the dominant narratives and stereotypes is at risk of being labeled as a "traitor" and "agent of Russia." Even an attempt to critically analyze conflicts and recent history is unacceptable.

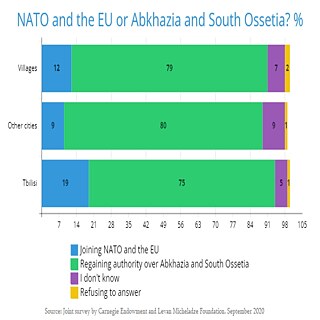

CRRC survey revealed that territorial integrity is even more essential to Georgians than membership in NATO and the EU. Therefore, any decision made by Tbilisi regarding conflicts is taken into account in this context. Any effort to alter accepted vocabulary or narratives is regarded as a danger to Georgia's national interests.

In its 2021 report, the OSCE refers to the circumstances in Abkhazia, along with Transnistria, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh, as a "protracted conflict syndrome" characterized by the collective acceptance of the intractableness of the conflict.

The role of the media has emerged as one of the most serious issues in the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict. Due to the fact that Georgians have limited opportunities to interact with Abkhazians, conflict-oriented discourse in the media encourages radical narratives, as shown by CARNEGIE EUROPE's project. The approach to news delivery also has a huge impact on shaping public perception of these events.

It will be challenging to change the rhetoric radically because doing so will spark protests in both communities. But according to Natia Chankvetadze, a researcher on peace and conflict, the non-governmental sector plays an enormous role because experts and the non-governmental sector are the most valuable resources. The researcher claims that they require more coordinated activity and internal agreement.

George Hewitt, a professor of Caucasian languages, asserts that Georgians and Abkhazians are able to interact effectively while they are in Western nations: One might even say that, on a personal basis, they become friends. In my opinion, it is important that such negotiations take place at this level.

A poll taken in April 2020 as part of the CARNEGIE EUROPE project "Future of Georgia" found that 69.7% of Georgian respondents were in favor of beginning direct communication between their government and the de facto authorities in Abkhazia.

I once met an Abkhazian woman in the hospital, Liana recounts. Abkhazians in Georgia have access to free healthcare. When I spoke to her in Abkhazian, she was overjoyed. She called a relative in Abkhazia and said, "Look, in Georgia, they speak to me in Abkhazian. We thought Georgians were man-eaters, but now I see how warmly they welcome us.”

It is hopeless to keep Georgian, Abkhazian and Ossetian societies captive to stereotypes, legends, and illusions, says Paata Zakareishvili. Proactivity is key to managing conflicts, not waiting for Russia to end its occupation and aggression. The most frequently discussed subject is "de-occupation," which is crucial but not decisive. Georgian society has a problem in that it doesn't consider its part of the responsibility. It only takes a few public changes to happen in Abkhazia or South Ossetia for us to have the illusion and hope that perhaps they will see us now, that is as if we are the right people on the correct path. We don't get the sense that we should also change how we feel about them.

”Look at the agreement in the interests of the Abkhazian people” - September 2022.