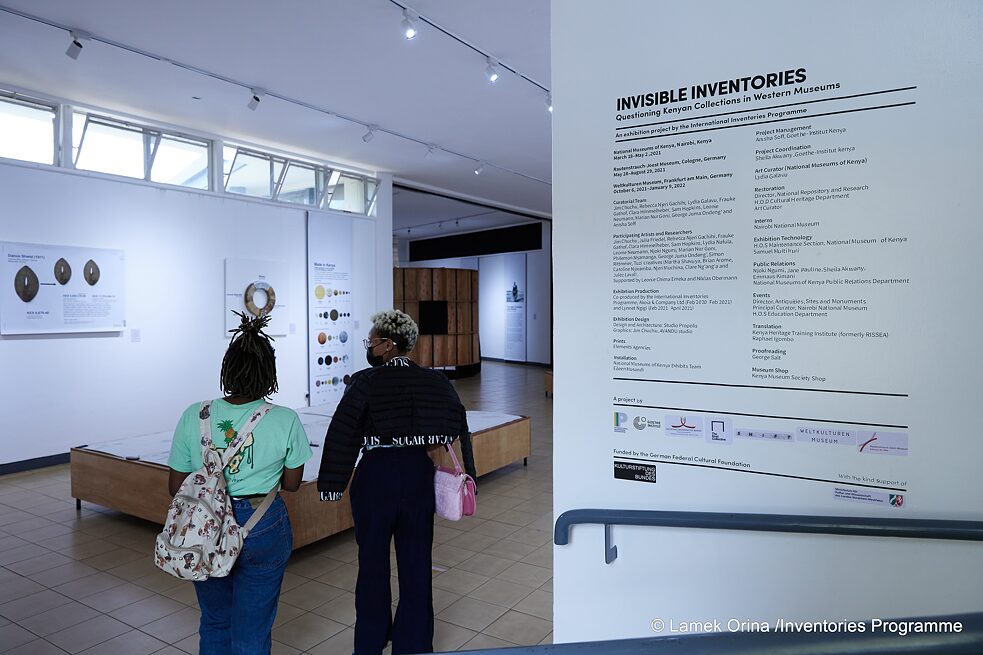

Exhibition series „Invisible Inventories“

Decolonising the discourse

The exhibition series “Invisible Inventories” showcases the results of an international research project whose aim is to build a database of Kenyan art objects in museums in Europe and North America. Shortly before the digital exhibition opening, Clara Himmelheber from the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and Frauke Gathof from the Weltkulturen Museum talk to “Latitude” about the work on establishing an equal relationship.

The exhibition series “Invisible Inventories” represents a concrete outcome of collaborative research by cultural heritage experts from Kenya and Germany. At the same time, it provides a solid basis for the demand for the return of colonial looted art to Kenya. What are your thoughts on this?

Frauke Gathof:

Frauke Gathof is a research assistant in the Africa department at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main.

| Photo (detail): © PicturePeople

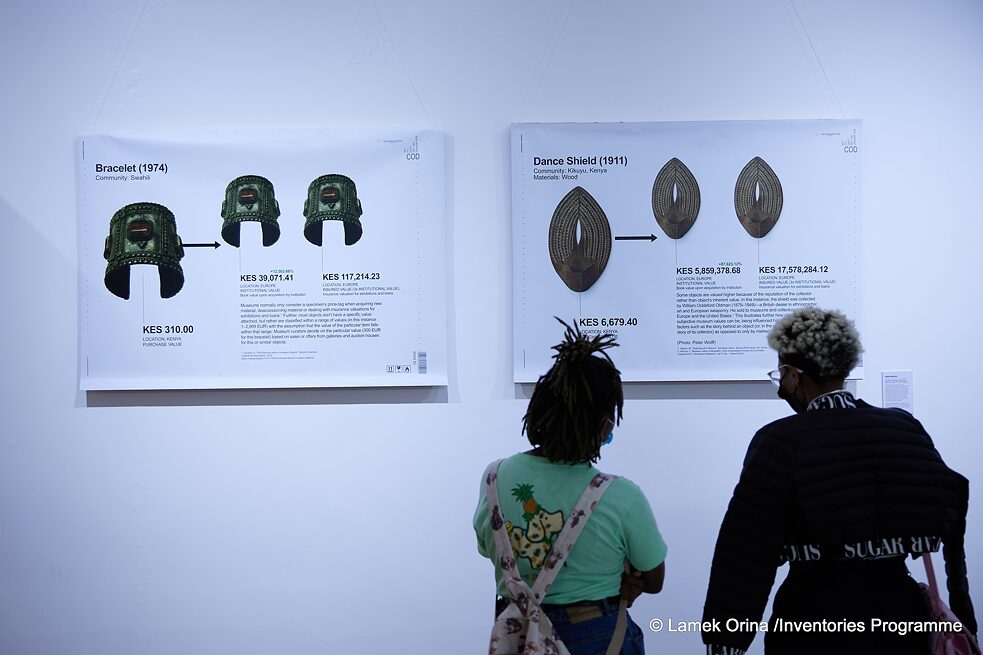

Part of the exhibition represents the research that the staff of the three participating museums (National Museums of Kenya, Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and Weltkulturen Museum) have jointly conducted on selected objects currently in the collections of the two German museums. In the process, in some cases quite different object biographies and present-day meanings for the communities from which they come, were reconstructed. In the case of some of these objects, we can conclude from the provenances that the objects were taken in a violent context, for example if the collector was part of the colonial government or profited from it. However, it has also been established that other objects that do not come from direct colonial contexts could also have a central significance in Kenya once repatriated. Our research was therefore not limited to objects from the colonial period. Although the central intention of our research was not to examine the conditions for restitution, dealing in a transparent manner with the knowledge about our collections is nevertheless an important part of the museum's work. So if demands for restitution arise from the project, we are of course open to them.

Frauke Gathof is a research assistant in the Africa department at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main.

| Photo (detail): © PicturePeople

Part of the exhibition represents the research that the staff of the three participating museums (National Museums of Kenya, Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and Weltkulturen Museum) have jointly conducted on selected objects currently in the collections of the two German museums. In the process, in some cases quite different object biographies and present-day meanings for the communities from which they come, were reconstructed. In the case of some of these objects, we can conclude from the provenances that the objects were taken in a violent context, for example if the collector was part of the colonial government or profited from it. However, it has also been established that other objects that do not come from direct colonial contexts could also have a central significance in Kenya once repatriated. Our research was therefore not limited to objects from the colonial period. Although the central intention of our research was not to examine the conditions for restitution, dealing in a transparent manner with the knowledge about our collections is nevertheless an important part of the museum's work. So if demands for restitution arise from the project, we are of course open to them.

To what extent does the “International Inventories Programme” contribute to open dialogue and encounter on an equal footing regarding the handling of looted art from colonial contexts?

Clara Himmelheber:

Dr. Clara Himmelheber is the head of the Africa Collection at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne.

| Photo (detail): © Christine Schröder

From the outset, the “International Inventories Programme” was designed to include as many different perspectives as possible. It is on this basis that the team, which consists of researchers and artists from Kenya, Germany and France, was assembled. Events such as the discussion series “Object Movement Dialogues” also specifically involve people from the global South, whose perspectives unfortunately still receive far too little attention in the international debates on provenance and restitution.

Dr. Clara Himmelheber is the head of the Africa Collection at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne.

| Photo (detail): © Christine Schröder

From the outset, the “International Inventories Programme” was designed to include as many different perspectives as possible. It is on this basis that the team, which consists of researchers and artists from Kenya, Germany and France, was assembled. Events such as the discussion series “Object Movement Dialogues” also specifically involve people from the global South, whose perspectives unfortunately still receive far too little attention in the international debates on provenance and restitution.

In the project itself, we decided that every voice would be heard equally and that everyone would be included in decisions. The various perspectives and opinions must be recognised and upheld, not levelled and equalised. We also intend to demonstrate this in the exhibition “Invisible Inventories”. But even despite this form of participatory organisation, we must continually reflect on ourselves, our own views, working methods and ways of communicating. That is an important part of this dialogue.

Frauke Gathof: I don’t think this process will be completed all that quickly. Shaping an equal relationship with each other is an ongoing process. For this to happen, a form of communication needs to be established that exposes and addresses what inequalities and injustices have existed and still exist in terms of power and self-determination. The recognition of the violence and injustice associated with the movement of objects in museums of the Global North is just the beginning. Even restitution can only be a piece of the puzzle in the reconciliation process, not a conclusion.

Together we were able to make a contribution to the discourse on restitution and identify new perspectives. We would like to decolonise this discourse with the help of the project and the exhibition. The countries and communities of origin must finally be given more responsibility with regard to the objects, their presentation, perception and above all, their locations.

To what extent does the exhibition contribute to greater knowledge both in Kenya and in Germany about the cultures of the societies of origin?

Clara Himmelheber: In the course of the research, the colleagues from the National Museums of Kenya interviewed members of the communities from which the objects originally came, and according to their own statements, this also broadened their own knowledge horizons – and ours, of course. Conversely, the interviewees learned through the research where some of their objects are located and were able to refresh forgotten knowledge about the objects through the photos, for instance. On the German side, Cologne residents of Kenyan origin were included in the discussions about the objects, which opened up another exciting perspective.

The opening of the exhibition is certainly not the end of the project. Are there concrete plans for the next steps?

Frauke Gathof: The exhibition itself will move on to the Weltkulturen Museum (6. October 2021–09. January 2022). The opening of the digital exhibition in Cologne on 27 May at 7 p.m. will coincide with official launch of the database. The first set of data will be published online. The database will continue to grow in the future and we hope to receive permission from other museums to post their data online. In addition, we have already initiated another research project, “Shifting Grounds” (funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation) in which, under the leadership of the National Museums of Kenya, Kenyan and German scholars in both countries will conduct research on further objects from the collections of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and Weltkulturen Museum.

The interview was conducted by Eliphas Nyamogo.