Edgar Leciejewski’s bildarchive

The Photo Book as Flip-Book

As we celebrate cinema’s 125th birthday in 2020, the flip-book and its ancient predecessors are where images learned to move. And it is where this essay series on Leipzig photographer Edgar Leciejewski started when I flipped the ten pages of his dine & dash series of the window views.

By Jutta Brendemuhl

Pocket cinema. Kineograph. Folioscope. Flip- or flick-book. The roots of moving image books — also a form of “image archive” as in Edgar Leciejewski’s bildarchive — can be traced back thousands of years to a bowl from present-day Iran, which upon spinning shows the motion sequence of a jumping goat. Think of it as the precursor to Eadweard Muybridge’s famous 1878 Horse in Motion “gif,” which marked the invention of chronophotography, the photographic technique that captures the passing of time. German film pioneer Max Skladanowsky presented his first moving image experiments in 1894 (a year before his big movie debut at Berlin’s Wintergarten) as a flip-book—he had invented a hand-crank camera but not yet a projector to cast the image. Walt Disney Studios honors their flip-book legacy with a Mickey Mouse flip-book animation as their production logo.

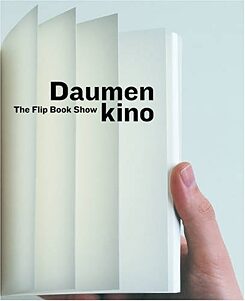

Flip-books, like photography, super 8 film, and other picture media, can have amateur or professional expressions. Kunsthalle Düsseldorf dedicated an entire exhibition to the flip-book in 2005 with 400 examples by Pedro Almodóvar, Jean Luc Godard, Angela Bulloch, Keith Haring, Tacita Dean, and others. Stuttgart artist residency Schloss Solitude held the first international flip-book festival in 2004. An expanded media example of how far flip-books can go is Volker Gerling’s travelling Daumenkinographie, an onstage show-and-tell image performance. And if you happen to be Finnish, your passport doubles as a flip-book of a roaming moose. Even NASA used this low-tech art form to promote its Deep Space 2 mission with a little animated gif.

The science behind the flip-book is based on the stroboscopic effect, an optical illusion of the perception of imaginary movement created from multiple static image stimuli, the same “trick” used in television. What’s missing is imagined: our brain fills in the visual blanks, contextualizes, and completes the viewing process and literally makes sense of a series of images. I wonder whether every one of us sees a different flip-book — or do we all insert the same information based on our shared visual experience of how a horse gallops or a kangaroo boxes?

Next up: You (and me) try our hands at DIY flip-books.