Ethics and Law

“Let’s decide on our own European standards and stick to them”

Do we need to establish common standards for artificial intelligence (AI)? In this interview, Karen Yeung, Interdisciplinary Professorial Fellow in Law, Ethics and Informatics at the University of Birmingham, explains why the legal regulation of technological developments is crucial – and urgent.

By Harald Willenbrock

Ms Yeung, in your book “Algorithmic Regulation” you explain that “there is little by way of recognition (at least in the Anglo-Commonwealth community of public law scholars) that a revolution in the process of governing might be afoot.” Why is that?

The recent Automating Society 2020 report by the German NGO Algorithm Watch depicts a rapid increase in both the number and diversity of automated decision-making systems (ADM) that are being rapidly taken-up in the public sector across Europe. Some of them utilise machine learning (ML), some of them do not, but in my view it’s important to talk about all of them. We need to take into account ADM and the automation of important areas of social and individual life in general more seriously. Yet many people seem to lack awareness of this, perhaps because these systems operate ‘behind the scenes’ in many cases.

Why is it so important to care about ethics when it comes to ADM and AI?

When we think about ethics in relation to AI systems, our concern is with our responsibilities for the adverse impact our actions have on others. If I knock you over by accident, what responsibilities do I have towards you? What are my duties towards other people and the environment? I think that’s a good starting point for discussion because “AI ethics” has become sort of the rubric for everything bad associated with AI. There are far too many “motherhood and apple pie” statements of important values that no one could disagree with. But we need to operationalise these principles in far more detail – to drill down to exactly what the responsibilities and duties of those who develop and deploy these systems are regarding their adverse impacts. We have many serious concerns in the here and now about how these systems are implemented, apart from serious problems on the not-too-distant horizon. They already adversely affect peoples’ lives in direct and tangible ways, and directly affect our social, cultural, politic and economic environment.

Can you give an example of how ADM affects our lives in a way that is ethically problematic today?

The most obvious one is the influence that social media has had on our public discourse and the integrity of our elections.

There have recently been many calls by civil society and even by politicians to regulate the flow of information on social media – such as banning false information and fake news. But we need to take the time to discuss what forms of information should be allowed, whether the platforms or the users should take responsibility and what measures could be effective. Is it in the nature of this rapidly evolving technology that its power and possibilities develop much faster than regulators can create new rules and regulations?

Well, the assumption that the law cannot keep up with technology is a common and frequently lamented misunderstanding. The problem is not with the law, but with social norms in the face of technological change. When, for example, wireless internet first emerged, there were questions about whether it was okay to log-in on somebody else’s wireless. At that time, there were no clear social norms about it, and many wireless signals were not initially password protected. Law has the capacity to reflect changing social norms and to apply well-established principles to new contexts. But when technological change produces novel forms of interaction in which the appropriate social norms of acceptability are still fluid and evolving, to make a law and say “X must do Y” would not necessarily be appropriate, at least not in democratic societies in the absence of public debate and discussion about what the law should require in these novel circumstances. So the mismatch is not between law and technology, but between societal norms and technological change.

Why is this true for the digital world in particular, and what is the situation in other highly innovative disciplines?

Let me give you an analogy that illustrates a serious difference between scientific cultures: In the world of human genomics, a maverick researcher in China attempted to intervene in the genome of a human embryo to produce what is commonly referred to as a ‘designer baby’. He was completely vilified for that because there was a clear recognition within the relevant scientific community that such a move would be morally inappropriate and controversial, particularly given the novelty of the technology and the profound consequences for individuals and society generally. So in the field of human biotechnology, there is widespread recognition within the scientific community of the societal and moral acceptability of any novel interventions, and the need for any such moves to be publicly debated. There is also recognition of the importance of having governance structures that are meaningful and legitimate and will enable and impose enforceable boundaries on technological innovations of this kind. In the digital branch we have quite the opposite. It’s all about moving fast and breaking things; and any bloke with a laptop and internet access can do digital transformation. The whole hacker cultural mentality is one of “fiddle and have a go”, fascinated with toys and capabilities. This, of course, would be perfectly fine if was confined to creating computer games. But society is not a computer game.

If any hacker can fiddle with society, as you put it, faster than social norms and laws can keep up – what risks does this pose?

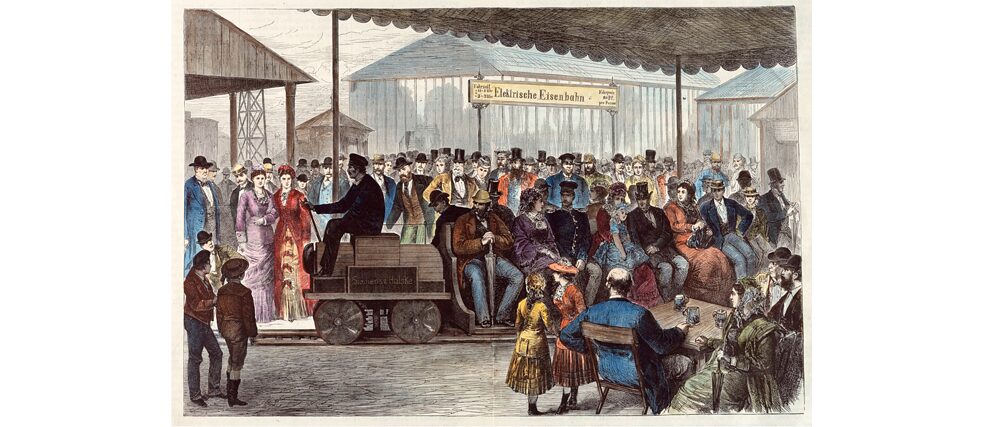

There’s a great precedent that illustrates our present circumstances: the first Industrial Revolution. Since then, the quality of our lives has undoubtedly improved. But as we did not take the external effects of that revolution into account, because we ignored and were unaware of the unintended side effects of the cumulative and aggregate effects of industrial activity at scale, we now face a serious climate catastrophe. Currently we are in danger of walking into the very same trap, and not just in terms of our ecological, but also of our political, social and cultural environments. There is a prevailing “digital enchantment”, the ridiculously naïve belief that algorithms and data will solve all our social problems if we are clever enough, and that the digital has no downsides. It might be great for some that Alexa can turn your lights on without touching a button, but we need to explore what having surveillance devices in our homes implies.

Presentation of the first electric railway, Berlin 1879: According to Karen Yeung, the first Industrial Revolution can be regarded as a precedent that illustrates our present circumstances – while the quality of our lives has improved, we now face a serious climate catastrophe.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/akg-images

But since everyone can individually decide whether they want to allow Alexa into their homes and thus whether they value comfort over privacy or vice versa, aren’t we all responsible for considering the downsides of the devices we use?

Presentation of the first electric railway, Berlin 1879: According to Karen Yeung, the first Industrial Revolution can be regarded as a precedent that illustrates our present circumstances – while the quality of our lives has improved, we now face a serious climate catastrophe.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/akg-images

But since everyone can individually decide whether they want to allow Alexa into their homes and thus whether they value comfort over privacy or vice versa, aren’t we all responsible for considering the downsides of the devices we use?

The US gun lobby has a popular slogan they use to counter calls to restrict the sale of guns: “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” But that statement is only partially true, for a gun is a far more powerful weapon than a handful of stones and a rubber band. The Silicon Valley high priests ignore all of this. Equally invisible is the work of the cheap labour provided by those in the Global South, all the energy consumption devoted to running our devices, and other adverse impacts that are intentionally designed to recede into the background to ensure the ‘seamless’ experience of the user.

Who is liable if an AI system does something wrong? There are many people involved in developing and using AI, so it could be the software developer, the data analyst, the owner – or the user.

There’s nothing special about AI in relation to the well-known ‘many hands’ problem, and I wish computer scientists would recognise that this is an age-old problem, for which the law has provided answers to for decades. The same challenges arise with complex products that entail complex value chains and the involvement of multiple organisations and individuals in the production process. The law resolves this by saying: you are all liable – and it is up to all those involved to apportion responsibility amongst themselves, for which the law will provide a solution. The crucial point is that the responsibility must not lie with the innocent bystander.

You were member of the EU’s High Level Expert Group on AI. What steps do you propose the EU take to set a framework for AI?

Well, again I would like to integrate ADM into the discussion rather than focusing solely on AI. All software-driven decision-making systems can operate at speed and at scale, and AI intensifies and accelerates the nature of the problem. The High Level Expert Group on AI commenced over two years ago and developed entirely voluntary ethics guidelines on trustworthy AI. They were based on very noble and aspirational principles, but unfortunately the group has no power to enforce them. The EU Commission has published a proposal for regulating AI, which it describes as offering a ‘risk-based’ approach. But despite its good intentions, the substance of its regulatory proposal was not risk-based at all. Honestly, it was pretty disappointing.

Why is there such reluctance to regulate AI?

In a crisis like the current one, in which productivity and economic prosperity are considered especially important, governments are looking to the tech industry to save us. Nobody wants to kill the golden goose. And the goose is constantly complaining, ‘if you impose any constraints on me, all my creativity and capacity will vanish.’ In other words, there is this strident, overwhelming unexamined article of faith that regulation stifles innovation, which is complete nonsense. If there were no laws, there would be no enforceable contracts and no property rights.

How high do you estimate the risk that companies will settle in countries whose jurisdictions have lower standards and that we will see worldwide competition for lower standards with regards to AI and ADM?

I don’t believe in that ‘if we regulate ourselves, we will be annihilated by China or the US’ notion. We need global agreements in areas concerning military technology and we need to provide agreed prohibitions on certain applications. But in the civil realm, if China or the US opt to go ahead with lower standards, then provided they do not dictate to us how we should live, it is likewise not for us to impose our collective values on them, at least up to a point. In Europe, it is up to the European public to discuss and decide what values we believe in, what kinds of practices we consider acceptable and in what sort of society we want to live in. And then we should live by our principles, and our norms and standards.

What would “sticking to our norms” mean practically?

Let me give you an example: If a Chinese medical application has been trained on data taken from its citizens in violation of their rights to privacy and without proper informed consent, we should not allow it to be imported to Europe. And if the online marketplace Alibaba and others want to play in Europe, they can do so, provided that they follow our rules. In this respect, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a wonderful example for our collective belief in data privacy and the need for legally enforceable standards. We need to set our own standards, then live by them.

Man browsing the Alibaba website: If foreign platforms like Chinese marketplace Alibaba want to play in Europe, they have to follow EU rules.

| Photo (detail): © Adobe

How realistic is it that this requirement can be met in a global environment? If, for example, I want to communicate with friends all over the world, I do so over the dominant platform Facebook which has been developed not by our, but by US standards.

Man browsing the Alibaba website: If foreign platforms like Chinese marketplace Alibaba want to play in Europe, they have to follow EU rules.

| Photo (detail): © Adobe

How realistic is it that this requirement can be met in a global environment? If, for example, I want to communicate with friends all over the world, I do so over the dominant platform Facebook which has been developed not by our, but by US standards.

You’re absolutely right, we’re still in the ‘move fast and break things’ cycle. But that’s slowly starting to settle down. The regulators are pushing back and there’s growing consensus that these platforms hold excessive power that needs to be tamed. If there’s political will of sufficient strength we can take these things seriously. But I do agree that we’re still a long way from there yet. We do need collective action.

Sounds as if you’re quite optimistic.

Not optimistic, but hopeful. What I do not know is how much damage will be done before we reach a stage of responsible digital innovation. Because it’s happening fast and it’s difficult for people to see and understand and it’s complex. For example, I do not know how many companies are tracking us while we’re conducting this interview over the internet, but it’s probably over 150, right? We feel so powerless that we allow things we would never accept in any other area of our lives.

What would you suggest people to do about data and security? There seems to be a common consensus that the individual can’t do anything about it.

Good question. I’d say: Don’t turn your brain off. Be more thoughtful in your digital interactions. Change your privacy settings and preferences to the necessary ones, don’t buy your children a smartphone until they are old enough to use it responsibly and, for heaven’s sake, please do not buy surveillance technology to operate inside your home and most intimate spaces.

What would be your worst-case scenario with regards to AI?

My worst-case scenario is a European, shiny version of China, that is an authoritarian regime with a mixture of governmental and tech company-power that is marketed in a more effective form: all shiny, happy people. It is not hard to imagine a future that bears a strong resemblance to Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World”.