Democracy and Diversification

“Acting in the here and now for equality”

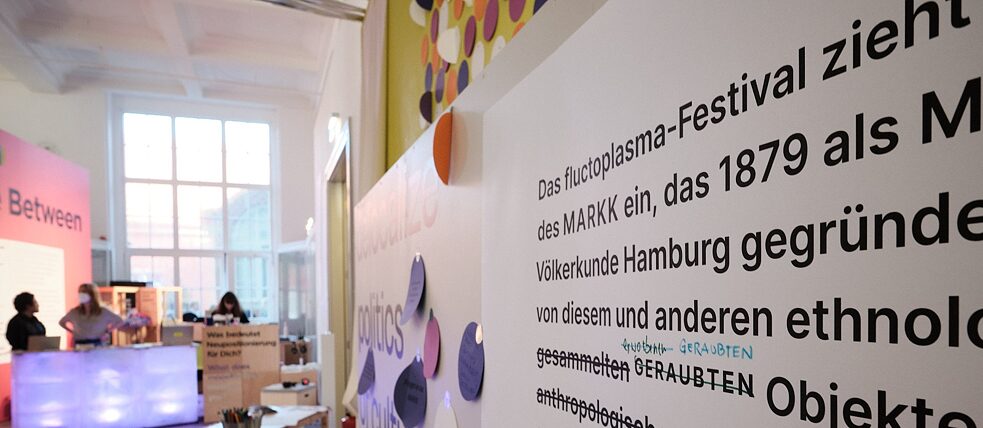

Demonstrating perspectives for living together in diversity is the mission of the makers of the interdisciplinary fluctoplasma festival, which took place in Hamburg for the third time last October. In an interview, project director Nina Reiprich and artistic director Dan Thy Nguyen talk about the lessons they have learned from their work, their relationship to optimism and the status quo of political education in Germany.

By Hendrik Nolde

The motto of the last fluctoplasma festival was #RetellingUtopia. In many respects, the situation of democratic societies worldwide currently seems rather dystopian. How much utopian optimism do you have in you?

Nina Reiprich: Optimism is more my domain. (laughs) We have enough optimism in us to do work that is driven by the desire to contribute to democratic dialogue in our society through artistic debate. But I also have to say that the current situation of worlds everywhere doesn’t make me feel particularly optimistic. Yet our work often creates many moments on a very small scale that illustrate that it’s worth fighting for spaces where people from very different backgrounds can talk to each other.

Dan Thy Nguyen: When I was growing up, art always worked according to a top-down model. The director – usually a man – said what was being done and everyone had to obey him. In our work, we try to develop forms of cooperation through working groups and exchange formats that are intrinsically democratic. Whether we succeed in living these on a day-to-day basis is another story, but that’s probably also part of democratic action – acting in the here and now for equality. One more biographical note: I have a relatively high degree of optimism, because for all the dystopian potential we see in the world now, I come from a refugee family and have thus experienced a different form of dystopia. With all our dystopian thoughts, we must not forget what incredible potential there is in our society to also develop utopias.

Potential is a good keyword when we talk about democracy and postcolonialism: the Enlightenment is still considered the cradle of modern Europe despite its colonial heritage. In this respect, how can we succeed in teasing out the potentials and renegotiating European thought in the 21st century and in a global context?

Dan Thy Nguyen: I believe that the current discussion reflects how to contextualise the Enlightenment in the 21st century and bring the ideas that strongly shaped Europe and the world to a new level. For example, what the Enlightenment definitely produced was the idea of human equality and many great things that came out of it: Pedagogy, philosophy, human rights. I think the problem is that a lot of inhumane things have been done in the name of human rights. In my view, though, this doesn’t make an examination of human rights obsolete; rather, our current task as such is the question of a radical renegotiation of humaneness.

Nina Reiprich: This context also raises the question: What counts as European thought? Many postcolonial and decolonial movements come out of the European context. And this raises further questions: Who is this European “we” that is always being talked about? In what dialogues did all these theories emerge? Even Kant didn’t write in a vacuum. That’s why I think it’s important to both create the dialogue now and to keep pointing out that there’s always been a global fertilisation and worldwide networking of postcolonial thought.

Dan Thy Nguyen: All the great thinkers of postcolonialism were in a hybrid dialogue. I think a big mistake we make is to say with certainty about the Enlightenment, “they were like this” while pretending that postcolonial movements emerged authentically, originally and without a dialogue with the rest of the world. We need to be careful not to create a false form of authenticity and think that it all came into being in a vacuum. These too are all spirits of their time and must be thought further. And that’s the beauty of being human.

Exchange on equal terms at the fluctoplasma festival 2022

| © Thomas Byczkowski

Your festival sees itself as a place of opinionated but compromising and respectful exchange. Has the perpetual loudness of discourse in social media made us forget how to tolerate contradictions and how to pay attention to the quiet voices?

Exchange on equal terms at the fluctoplasma festival 2022

| © Thomas Byczkowski

Your festival sees itself as a place of opinionated but compromising and respectful exchange. Has the perpetual loudness of discourse in social media made us forget how to tolerate contradictions and how to pay attention to the quiet voices?

Nina Reiprich: Formats in which I can somewhere participate anonymously have certainly supported this development. But I also think – very specifically for Germany – that there is almost no democratic education and thus joint, constructive, democratic debate is not anchored in the educational system. So it’s not surprising when 20 years later no adults emerge who are used to really arguing with each other respectfully. Basically, I agree: I believe that loud voices are much more successful now, completely independent of whether they are louder for peaceful coexistence for all. And the fact that quieter voices that try to engage in dialogue are very quickly beaten down is a difficulty that we also often encounter.

Dan Thy Nguyen: The very fact that we are talking about this now and have recognised this phenomenon of a learned culture of the extrovert reveals that loud voices are not necessarily always the more intelligent ones. Additionally, I believe that all major democratic movements have always been very passionate. The emergence of democracy was a passionate struggle and any further development of democracy also had to be fought for. The interesting thing about a democracy is that it can and must endure struggles if it has enough inner defences. The only question is how we deal with it. Have we implemented enough instruments in democracy? Do we have a democratic culture of political education that starts from an early age to understand that dialogue, arguing, even conflict, are part of democratic society? I think we as democrats are sometimes still very bad at being democratic.

Nina Reiprich: I would like to disagree a little on this point. Sure, democracy was fought for, but that was in clear opposition to a democracy that didn’t exist yet. Within democracy today, though, the natural opponent, so to speak, is missing. This has turned the struggle into a very bureaucratic dispute that has lost many people because what it’s actually about is no longer clearly communicated. This is where we have to start, both in cultural and political education, but also in the form of our administration and political participation. According to the motto, “Where do we actually have opportunities to do something?”

Dan Thy Nguyen: We need to overcome the bureaucratic, because we all have to be passionate democratic people to achieve a living democracy. We have the instruments that have been put in our hands for a living democracy. But we don’t use them sufficiently.

One of your most important concerns is to negotiate issues such as diversity, equality, and anti-racism not only within socio-cultural filter bubbles, but across society as a whole and without barriers. Is there a need for a democratisation of access to political and cultural discourse in this regard as well?

Both: Yes. (laugh)

Dan Thy Nguyen: But there’s something we can add to this simple “yes.” We shouldn’t overestimate culture and art as democratic forces. They can only function well in interaction with the other fields of the democratic: the social, the political, education. It’s like this: Art is one building block. That’s why our festival is also built from these different elements. It’s not only art, but also discourse.

Nina Reiprich: I previously worked in a project in which needs were identified and artistic projects developed from neighbourhood work. It often became extremely clear how important social and political changes are. I can put people on a stage as often as I like – if these people have no work permit and no flat where children can do their homework in peace in their own room; if these people have three jobs so that they can feed their children, then we don’t have to talk about whether they have access to the Deutsches Schauspielhaus. That is also a relevant question. And it is also important that these stories are told on the stages of the Deutsches Schauspielhaus and that all people feel welcome there. But it is our joint responsibility as a society to create a coexistence in which children have enough to eat, can go to school and are supported; in which parents have places to turn to when they are at a loss and in which people who want to work are allowed to do so. That’s the basis for people to be able to deal with questions like, “What political parties are there and which one should I vote for?” That’s why art can set topics and it can draw attention. But something has to change in other places.

Dan Thy Nguyen: We have to create equal rights and continue these traditionally bottom-up struggles. But the big institutions also have to live up to their democratic and social responsibility. That’s why fluctoplasma strives to work with big institutions and remind them: “You set topics and you get funding. That’s democratic money, so you have the responsibility to create something for democracy.”

Dan Thy Nguyen, you once compared the aesthetics of fluctoplasma to a futuristic gumball machine. Let’s turn the wheel of the machine together – what is in the little capsules that can contribute to the emergence of a democratic society of the future?

Nina Reiprich: Maybe a kind of sedative so that we are able to listen to each other better.

Dan Thy Nguyen: I think all these recognition battles we are in are very important. The crucial question is, what do we do with it? What tools do we develop now for this capsule? Without forms of forgiveness and processing, we won’t get anywhere. The dispute itself is important as a form of socialisation, but it’s also important to build bridges and walk over them. And perhaps in addition: Problems often look bigger from the outside than they truly are and sometimes you have to dig deeper to find out what tools we need for our future.

Then perhaps the metaphor of the gumball machine will help us again to put things in perspective and not make them bigger than they need to be?

Dan Thy Nguyen: Many of the issues discussed today are illusory giants, like in Momo. The closer you get, the smaller the problems suddenly become. When you stand right in front of them, they seem so big that you get the feeling you can’t cope with them. But we have no other choice. We have to overcome them if we all want to live together in dignity in this world.

About the project

fluctoplasma - Germany's interdisciplinary festival for art, discourse and diversity will take place for the fourth time from 26 to 29 October 2023. At the junction of aesthetic and social reflections, perspectives for living together in diversity will be presented, both as an immediate experience, in extremely diverse venues of Hamburg's cultural scene, and online via live streaming. The aim of the four-day event series: to promote political education, social bonding and collective movement through artistic means in order to shape a more solidary, pluralistic and just coexistence. Through exhibitions and concerts, film screenings and DJ sets, interactive installations and spoken word performances, talks, panels and workshops, answers to urgent questions about the future will be outlined: Which utopias of community have had their day, need an update or call for more inclusive basic ideas than those of the European Enlightenment? What new realities do we have to design and how do we manage this together with the increasingly perfectible tools of democracy?