CAPE TOWN’S AFRICAN FOODWAYS: A story of migration

Power Talks Cape Town began in a Quantum, the small Toyota bus commonly used as a taxi in these parts. Our guide, Jane Nshuti, a Rwandan food curator and chef, is taking us on one of her food-sourcing routes. The ‘us’ in question is twenty artists, curators, researchers, and activists from different walks of life, moving together along the 17 kilometres that make up Voortrekker Road. Built in 1845, this was the first arterial road leading out of Cape Town.

The name ‘Voortrekker Road’ was conferred upon the route in 1938, in commemoration of ‘Die Groot Trek,’ the migration of Dutch-descended settlers from the British colony of the Cape between 1835 and 1846, who left the Cape in search of an ‘autonomous’ new home upcountry.

On our food journey, we pass Maitland, where the search for home is rendered visible. Makeshift structures built with planks, tarpaulins, or corrugated iron line the border of a cemetery. Cape Town is a city preoccupied with the delineation of space, its Apartheid legacy the inheritance of a racialised spatial design. The city can no longer continue its game of hide-and-seek with people it is unwilling to make room for. An imposed transience haunts its residents. The story of migration made under duress – often violent duress – is one Cape Town knows all too well.

The foodways for African food traders follow Cape Town’s pervasive migratory patterns. For example, you will be hard-pressed to find a better source of injera than in Bellville, which is home to a large community of Somalis and Ethiopians. Other significant population groups that have set up enclaves in the city are Rwandans in Retreat, Kenyans in Summer Greens, and Nigerians in Parklands. The foods that evoke nostalgia for these communities are transported into the city in large container trucks. Popular, fresh foods such as plantain sell out within three days of arrival, with WhatsApp the preferred communication channel alerting people to the arrival of the longed-for foods. Little wonder WhatsApp has become such a trusted tool for community-building across the African diaspora.

Jane starts our tour at Super Gambela food store in Salt River. The shop’s window is covered in bold white lettering, which alerts passers-by to the promise of kwanga, ngai ngai, mfumbwa, soso and pondu inside. At U.C.J. Trading, also in Salt River, the shelves are lined with De Grace tomato paste, garri, fufu, shredded cassava and unmarked plastic containers bearing the distinctive red hue of palm oil. In another shop, the Kenyan proprietor offers us bright pink and yellow baobab, which stains our tongues. We carefully scour the stores: some of us stuff our bags and pockets with Indomie instant noodles, beans, flours, and teas, while others trade family recipes across food aisles. Jane haggles with the owners, carefully gathering ingredients for the feast we will soon prepare.

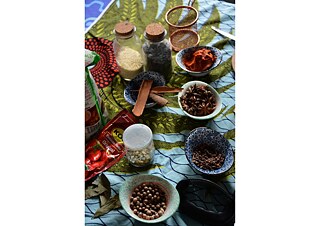

At Jane’s house we are greeted by a long table covered with different kitenge. Placed on top of the kitenge are various sized bowls, bottles, knives, and other kitchen utensils. Potatoes are sprawled across one of the chopping boards, while an unplugged pressure cooker sits expectantly. Jane has a piece-meal approach to cooking. She moves across the room handing out tasks. Peel potatoes, grate garlic, wash and cut okra, boil tamarind. There is no set time given for each task. Our job is to pay attention to how the food responds to each action. It is these incremental shifts of the bubble, the boil, the thickening of liquid which are indicators of our progress. There is a kind of bean Jane remembers eating growing up which was a pain to cook. The beans were encased in a hard shell that had to be peeled one by one. The process was hours long and often relegated to the children. Jane remembers hating the process at the time, but she now has fond memories of the stories shared over the peeling bucket. As Rwandan families became smaller and employment and other demands began to encroach on their time, the popularity of the bean dwindled. In Jane’s home, we move between stations without rigid surveillance or justification. Slowly, the air begins to fill with the aroma of different foods hanging thick in the air. Each one beckoning us to gather and feast.

Laid out before us is a spread of fried okra, garlic-infused roast potatoes, chickpeas, chilli sauce, and a lovely homemade pineapple-and-ginger concoction, all made by our own hands. We load our plates buffet style and squeeze ourselves onto couches or sit on the floor with plates cradled in our laps. By the end of our meal we are sated and content, having built community through food. Today food served as a conduit for memory, for community, and for belonging. The journey through Cape Town’s migrant foodways a reminder of how home is also forged through tastes and textures that coat our teeth and stick to our palate.

Power Talks Cape Town’s opening session also introduced us to the ethos with which Ukhona Ntsali Mlandu, the director of Greatmore Studios, curated the programme. The food tour and the events that succeeded it were an invitation to explore through the senses the city’s contested histories of power. Power is often framed through the lens of domination and subjugation. Power Talks Cape Town was an invitation to interrogate the multiplicity of powers, framed both positively and negatively, prevalent in the city. The programme reinforced to me that to understand a city one needs to discern not only why and how people move around physically, but also – equally importantly – one needs to acknowledge what pulses within, what is emotionally resonant, what fundamentally moves people.The story of big cities is inevitably the story of movement. The ways in which a city moves provides insight into the people who move within it. Anyone who has taken a taxi in Cape Town knows that the city calls out to you. It eschews Johannesburg’s choreography of hand signals for gaatjies (assistant taxi operators) who punctuate the air with yells of ‘Bellville, Town!’ or ‘Mowbray, Kaap!’

Power Talks Cape Town began in a Quantum, the small bus commonly used as a taxi in these parts. Our guide, Jane Nshuti, a Rwandan food curator and chef, is taking us on one of her food-sourcing routes. The ‘us’ in question is twenty artists, curators, researchers, and activists from different walks of life, moving together along the 17 kilometres that make up Voortrekker Road. Built in 1845, this was the first arterial road leading out of Cape Town.

The name ‘Voortrekker Road’ was conferred upon the route in 1938, in commemoration of ‘Die Groot Trek,’ the migration of Dutch-descended settlers from the British colony of the Cape between 1835 and 1846, who left the Cape in search of an ‘autonomous’ new home upcountry.

On our food journey, we pass Maitland, where the search for home is rendered visible. Makeshift structures built with planks, tarpaulins, or corrugated iron line the border of a cemetery. Cape Town is a city preoccupied with the delineation of space, its Apartheid legacy the inheritance of a racialised spatial design. The city can no longer continue its game of hide-and-seek with people it is unwilling to make room for. An imposed transience haunts its residents. The story of migration made under duress – often violent duress – is one Cape Town knows all too well.

The foodways for African food traders follows Cape Town’s pervasive migratory patterns. For example, you will be hard-pressed to find a better source of injera than in Bellville, which is home to a large community of Somalis and Ethiopians. Other significant population groups that have set up enclaves in the city are Rwandans in Retreat, Kenyans in Summer Greens, and Nigerians in Parklands. The foods that evoke nostalgia for these communities are transported into the city in large container trucks. Popular, fresh foods such as plantain sell out within three days of arrival, with WhatsApp the preferred communication channel alerting people to the arrival of the longed-for foods. Little wonder WhatsApp has become such a trusted tool for community-building across the African diaspora.

Jane starts our tour at Super Gambela food store in Salt River. The shop’s window is covered in bold white lettering, which alerts passersby to the promise of kwanga, ngai ngai, mfumbwa, soso and pondu inside. At U.C.J. Trading, also in Salt River, the shelves are lined with De Grace tomato paste, garri, fufu, shredded cassava and unmarked plastic containers bearing the distinctive red hue of palm oil. In another shop, the Kenyan proprietor offers us bright pink and yellow baobab, which stains our tongues. We carefully scour the stores: some of us stuff our bags and pockets with Indomie instant noodles, beans, flours, and teas, while others trade family recipes across food aisles. Jane haggles with the owners, carefully gathering ingredients for the feast we will soon prepare.

At Jane’s house we are greeted by a long table covered with different kitenge. Placed on top of the kitenge are various sized bowls, bottles, knives, and other kitchen utensils. Potatoes are sprawled across one of the chopping boards, while an unplugged pressure cooker sits expectantly. Jane has a piece-meal approach to cooking. She moves across the room handing out tasks. Peel potatoes, grate garlic, wash and cut okra, boil tamarind. There is no set time given for each task. Our job is to pay attention to how the food responds to each action. It is these incremental shifts of the bubble, the boil, the thickening of liquid which are indicators of our progress. There is a kind of bean Jane remembers eating growing up which was a pain to cook. The beans were encased in a hard shell that had to be peeled one by one. The process was hours long and often relegated to the children. Jane remembers hating the process at the time, but she now has fond memories of the stories shared over the peeling bucket. As Rwandan families became smaller and employment and other demands began to encroach on their time, the popularity of the bean dwindled. In Jane’s home, we move between stations without rigid surveillance or justification. Slowly, the air begins to fill with the aroma of different foods hanging thick in the air. Each one beckoning us to gather and feast.

Laid out before us is a spread of fried okra, garlic-infused roast potatoes, chickpeas, chilli sauce, and a lovely homemade pineapple and ginger concoction, all made by our own hands. We load our plates buffet style and squeeze ourselves onto couches or sit on the floor with plates cradled in our laps. By the end of our meal we are sated

and content, having built community through food. Today food served as a conduit for memory, for community, and for belonging. The journey through Cape Town’s migrant foodways a reminder of how home is also forged through tastes and textures that coat our teeth and stick to our palate.

Power Talks Cape Town’s opening session also introduced us to the ethos with which Ukhona Mlandu curated the programme. The food tour and the events that succeeded it were an invitation to explore through the senses the city’s contested histories of power. Power is often framed through the lens of domination and subjugation. Power Talks Cape Town was an invitation to interrogate the multiplicity of powers, framed both positively and negatively, prevalent in the city. The programme reinforced that to understand a city one needs to discern not only why and how people move around physically, but also, and equally importantly, one needs to acknowledge what pulses within, what is emotionally resonant, what fundamentally moves people.

Faye Kabali-Kagwa can be found online at @katiiti_k (IG) and @faye_kk (Twitter/X)

Jane Nshuti, Rwandan chef and food curator, introducing different foods on the tour | © Rui Assubuji

Writer and curator Phokeng Setai stands inside a food store in Salt River | © Rui Assubuj

Ingredients laid out on Jane’s table | © Rui Assubuji

People serving food prepared in a collective cooking session | © Rui Assubuji

Enjoying the feast in Jane’s home | © Rui Assubuji