Dialects of Power: A Reflection on Concepts

Power(ful) concepts

Power as it is experienced by marginalised communities often comes with negative, oppressive connotations. This is the kind of power that I, a young black woman from Mfuleni in Cape Town, am familiar with and experience as I navigate life in this city.

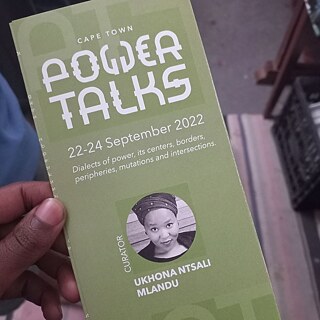

I find myself increasingly curious about power: what does it means to me personally, for my work as a community activist, as a mother? The Power Talks Cape Town series, curated by Ukhona Ntsali Mlandu, director of Greatmore Studios, presented an opportunity for us to consider the concept of power in some of the ways it shows up in our city. The programme challenged us to ask such questions such as: what does power taste, sound, and feel like? When is it generative? When is it expressed in dancing? What influence does it have on what and how we eat? Can power be expressed as joy? Can it connect people and help to build community?

Researcher, writer and thinker Thiyane Dude facilitated the two-day Power Talks Cape Town Programme, which started with a guided food tour led by Jane Nshuti, a chef specializing in African-Diasporan vegan cuisine. Before we set off, Thiyane asked us to introspect on what we understand power to be. He asked what we would need to restore power to and within our communities, many of which were denied power by Apartheid. He asked us to imagine power as soft, power as kind, and power as contained in the practises that we take for granted, such as eating, for example.

What does power taste like?

Jane escorted us into an ecosystem of stores run by different African immigrant communities, which to me as a local had until this moment blended into the other stores I occasioned for food. Jane reminded me that food is also a way for those who are far from home to maintain a connection with home. The ingredients we were introduced to took me on travels in my mind, tracing journeys that stretched from Cape Town’s food system beyond many borders. There was fish, dry almost to the bone, rich in its smell and preserved by salt. This fish can withstand the long distances it travels before it arrives inside the stores lining the streets of Cape Town, there to be bought and carried into the homes of those who long for a taste of home. This food is international, arriving in big trucks coming from Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and other countries in Africa; it travels in hundreds of bags, which first stop in Johannesburg before being distributed to the rest of the country.

Jane vividly described how all this food gets to us, emphasising that it is a thriving system that sees farms in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, among others, growing and selling food to a growing market of migrants who are living, working, and making new homes in Cape Town. Demand for this supply of food is managed through WhatsApp groups: the arrival of goods is announced to communities who find each other socially, through church, and in other spaces. The arrival of dried fish, yams, and plantains is said to bring about a rush of excited customers who know they must respond quickly, before everything is gone.

Store owners received us warmly, many inviting us to taste unfamiliar items and to buy food to take home. Jane slowly collected the ingredients she would need to cook lunch; and guess who would be doing the cooking? Us, of course. From the food tour we moved to Jane's home, where everyone was tasked with preparing and making a part of the lunch that would be served. This is where, in my own self-serving attempts to find the easiest task, I ended up taking on probably the least-good-idea. I found myself with a grater and a pile of garlic cloves, which I had to grate into a mound of fine garlic to be used in some of the dishes. Of course, I believe in the power of garlic on my meals – just not its smell lasting for days on my fingers.

As we prepared the ingredients, our conversations moved to reflections about the plate, and the different journeys the food had gone on before it got there. It was as if, through the lens of the food we had just prepared, a light had been shone into a dark room to which our eyes had become completely adapted, and it was a glorious relief to see the scale of the African food system that has developed in a largely westernised Cape Town. When I reflect on this particular session, I remember the ways in which food and expressions of identity are intertwined. People’s stories are told through the food they eat, and for anyone who wants to be reminded of home, when they are far away, the easiest way to be ransported back is by enjoying the familiar tastes of home. Where does coconut milk, for example, take them in their memories? These food practices are a way of making home, just as they are a way of restoring belonging inside the home. A way of restoring power, through the plate.I did not know what to expect on Chef Jane’s guided food tour. All I knew, was that we would be a small group. To me, ‘small group’ implied ‘intimate’, which means talking to people is unavoidable. This made me nervous. We assembled at Greatmore Studios in Woodstock, and I was reassured to see Chef Jane’s familiar face, which I often see at Bertha House, the activist community space where the organisation I work for, Food Agency Cape Town, is based.

Jane escorted us into an ecosystem of stores run by different African immigrant communities, which to me as a local, had until this moment blended into the other stores I occasioned for food. Jane reminded me that food is also a way for those who are far from home to maintain a connection with home. The ingredients we were introduced to took me on travels in my mind, tracing journeys that stretched from Cape Town’s food system beyond many borders. There was fish, dry almost to the bone, rich in its smell and preserved by salt. This fish can withstand the long distances it travels before it arrives inside the stores lining the streets of Cape Town, there to be bought and carried into the homes of those who long for a taste of home. This food is international, arriving in big trucks coming from Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and other countries in Africa; it travels in hundreds of bags, which first stop in Johannesburg before being distributed to the rest of the country.

Jane vividly described how all this food gets to us, emphasizing that it is a thriving system that sees farms in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, among others, growing and selling food to a growing market of migrants who are living, working, and making new homes in Cape Town. Demand for this supply of food is managed through WhatsApp groups: the arrival of goods is announced to communities who find each other socially, through church, and in other spaces. The arrival of dried fish, yams, and plantains is said to bring about a rush of excited customers who know they must respond quickly, before everything is gone.

Store owners received us warmly, many inviting us to taste unfamiliar items and to buy food to take home. Jane slowly collected the ingredients she would need to cook lunch; and guess who would be doing the cooking? Us, of course. From the food tour we moved to Jane's home, where everyone was tasked with preparing and making a part of the lunch that would be served. This is where, in my own self-serving attempts to find the easiest task, I ended up taking on probably the least-good-idea. I found myself with a grater and a pile of garlic cloves, which I had to grate into a mound of fine garlic to be used in some of the dishes. Of course, I believe in the power of garlic on my meals – just not its smell lasting for days on my fingers.

As we prepared the ingredients, our conversations moved to reflections about the plate, and the different journeys the food had gone on before it got there. It was as if, through the lens of the food we had just prepared, a light had been shone into a dark room to which our eyes had become completely adapted, and it was a glorious relief to see the scale of the African food system that has developed in a largely westernised Cape Town.

When I reflect on this particular session, I remember the ways in which food and expressions of identity are intertwined. People’s stories are told through the food they eat, and for anyone who wants to be reminded of home, when they are far away, the easiest way to be transported back is by enjoying the familiar tastes of home. Where does coconut milk, for example, take them in their memories? These food practices are a way of making home, just as they are a way of restoring belonging inside the home. A way of restoring power, through the plate.

What does power sound like?

Ukhona Mlandu, while introducing the Sound as Power session at the Radical Book Store in Woodstock (now moved to Bertha House in Mowbray), posed a question that I still think about months later: How do we deal with power that manifests and enacts itself negatively – power that is the lived reality for those who are socially and economically marginalised? I rephrase this and ask: what do I do when I am confronted by such power? This brings me back to my own power, and reminds me not to feel powerless or disempowered, even when I may not fully recognise it, or when I am backed into a corner with nowhere to go, and am confronted by an oppressor. What does a person do in such a situation? Do you put peace-building aside and fight tooth and nail to regain power? Do you give in and tolerate a longer-term victory? Do you walk away?

Erasure was another theme that emerged as we encountered the band Kujenga. Here, sound provided an immersive celebration of Black culture, and just of being alive, and I observed an eventual inability to sit down while this musical experience took place.

A short documentary was played showing how the Muslim communities of Woodstock and Salt River had to adapt old traditions into new ones during the Covid-19 lockdowns, which prevented people from going to mosques. During this time, the muezzin’s call brought people onto their balconies and stoeps, to feel a sense of worshipping together even as they were social-distancing. My criticism of this session is that in trying to understand the complexity of power from every different angle, it became hard to connect all the dots the curators wanted to join together. Then again, perhaps this session did not want the dots to be easily connectable (if there is such a word), but rather to highlight the contradictions of the context, Cape Town, in which this power is expressed.

The notion of sound as an instrument of joy led me to the question of spaces in which to connect with indigenous modes of song-making. Drumming, dancing, and singing have all been pushed to the margins by the demands of modern life, and kept even further away by deliberate colonial policies that framed such expression as being associated with witchcraft, as something to be viewed with suspicion and hostility. What does it mean for communities to reconcile their loss of culture and recreation? These questions, in turn, bring me back to the idea that power is not only lost as the result of a direct encounter with one's oppressors; power is also something that can just fizzle out over time. This is the kind of loss which is felt, but somehow, in its invisibility, cannot be accounted for. It is the loss of one's humanity, or the loss of a collective humanity. A process that is slow, and gradual, and whose results are only realised when it is much too late.

Sanelisiwe Nyaba can be found online at @onionscrytoo_

Sound as joy | © Sanelisiwe Nyaba

Meeting point: Greatmore Art Studios | © Sanelisiwe Nyaba

Taken from inside the bus during the food tour | © Sanelisiwe Nyaba

Lunch at Chef Jane’s | © Sanelisiwe Nyaba