In her debut novel, Mia Raben tells the story of a Polish carer in Germany. She travels to Hamburg, initially burnt out, but then experiences an unexpected happy ending.

Journalist and author Mia Raben has a Polish mother and a German father. Only German was spoken in her parental home, but Mia Raben was interested in her mother's country of origin from an early age. Motivated by frequent visits to her relatives in Łódź, she endeavoured to learn Polish as an adolescent. After graduating from high school, she went to Krakow in the mid-1990s and took a Polish course there.Between Warsaw and Hamburg

Back in Germany, she began her journalistic career, studied at the Berlin School of Journalism and lived in Warsaw for a while as a freelance correspondent in the noughties. Although she sometimes feels like an impostor in this country that is ‘so familiar and at the same time so foreign’ to her, she is fascinated by the great love of freedom and people – qualities that are somewhat underdeveloped in the Germans with their “tendency towards strictness and conformity”. According to Raben, Germans rarely show curiosity or goodwill towards Poles, but usually react from above with a “mixture of consternation and pity” (quoted from a portrait of Mia Raben on the website Porta Polonica, a documentation centre on the culture and history of Poles in Germany).Raben began writing short stories in Warsaw. In 2007, her life took her back to Germany, where she had two sons and continued to work as a journalist. However, she continued to write literature, studied creative writing in Leipzig and received a research grant from the Hamburg Department of Culture and the Hamburg House of Literature at the end of 2022. This research in Łódź, her mother's hometown, was incorporated into her debut novel Unter Dojczen. Mia Raben spoke to workers in the textile industry there, quite a few of whom had lost their jobs, which is why they felt compelled to go to Germany as carers.

Like parcels on a doorstep

The main character in Mia Raben's book is Jola, who is in her mid-fifties. She has been working as a geriatric nurse in Germany for years and is not only scarred by the hard work, but has also experienced racism, classism and exploitation and is traumatised by personal humiliations. She has to take a break due to burnout. But because she is in debt to a Polish loan shark, she cannot afford to take a long break.So at the beginning of the novel, she is back in the familiar minibus that takes her and many other Poles to work in Germany. She summarises the situation for the care workers, who call themselves “betrojerinki”, as follows: “Most of them were new, they had only been commuting for a short time and still thought they had hit the jackpot. Next to them were the old hands, who had long since got used to being delivered like parcels to someone's doorstep in Germany. She herself was one of them.”

Hamburg as a stroke of luck

Jola's destination this time is Hamburg. She is hoping for better working conditions, as she is now officially registered and will be working on behalf of an agency: with a decent salary, insurance and fixed working hours. She ends up in the house of a doctor's family in a residential neighbourhood in Hamburg, where she even has her own small flat and can't believe her relative good fortune. She has to look after her grandmother called Uschi, who, according to her daughter-in-law, “isn't very easy”. She is a control freak, manipulative and “pathologically jealous”. Some carers have cut their teeth on Uschi.Uschi is quite up for it, but is indeed stubborn and prickly. However, Jola shows a lot of sensitivity and quickly finds a good connection with her – perhaps also because Uschi grew up in East Prussia as a child and had a beloved Polish nanny there.

The dark sides

In addition to the developing relationship between Jola and Uschi, the novel also has a side story. On the bus journey to Hamburg, Jola met Kuba, a craftsman who she initially dismisses as a drunken country bumpkin from Masuria. Nevertheless, she likes Kuba's somewhat old-fashioned charm and his politeness. She later finds him a job through Uschi's son. When Kuba is temporarily homeless and Jola secretly lets him spend the night in the house's sauna, this leads to a conflict.There are also stories about the darker sides of Jola's life. For example, her years of working in Germany led to her becoming estranged from her now grown-up daughter Magda. Contact was even broken off completely, as Jola even felt compelled to plunder Magda's savings account due to a lack of money. Jola spent a long time working on an honest and conciliatory email to send to her daughter.

Utopia with linguistic icing on the cake

Mia Raben's novel tackles a topic that is often dealt with in the media and non-fiction books, but carers are rarely mentioned in literary works. She tells Jola's story straightforwardly and unpretentiously, interspersing a few sentences of Polish every now and then.With this problem-laden topic, Raben could easily have told a disillusioning story about the exploitation of Eastern European carers. But she strikes a conciliatory tone. Jola and her “seniorka” Uschi grow closer, Jola is finally given a surprising perspective, and there is even a happy ending for Kuba. There are a few “slips into kitsch” and some “linguistic sugar-coating”, according to Juliane Bergmann on NDR Kultur, but Raben has not opted for a completely bleak and abysmal description of the situation, but for a – somewhat fairytale-like – utopia.

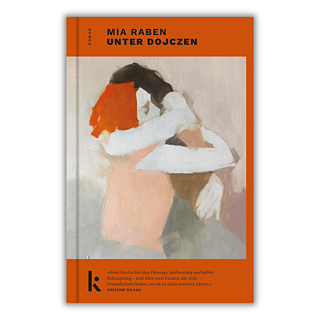

Mia Raben: Unter Dojczen. Roman

München: Kjona, 2024 224 p.

ISBN: 978-3-910372-27-6

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

01/2025