Until recently, few people remembered that hundreds of Jews were sent to their death from Dresden’s Alter Leipziger Bahnhof. André Lang, Holger Knaak and fellow campaigners are determined to change this. Their mission is to create a place where people can connect with Jewish life. On the International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of National Socialism, Dresden journalist Andreas Roth interviews the two campaigners.

Lang: This place moves me profoundly. It has to do with my family’s history. I was born in 1946 in Manchester, where my parents lived in exile with my sister and myself. As a communist, my father actively fought against the Nazis and was imprisoned for this. My mother came from a Hungarian-Jewish family. Many of our Hungarian relatives were sent to ghettos and Nazi extermination camps. Alter Leipziger Bahnhof is a powerful symbol of the suffering inflicted on people during National Socialism.

Mr Knaak, eight years ago, your artists’ collective, blaueFABRIK, moved into a side wing of Alter Leipziger Bahnhof. At that time, were you aware of the historical significance of the site you were occupying?

Knaak: In the first few years, I didn’t know anything. All I knew was that the station was the endpoint of one of the world’s oldest, long-distance rail lines, which had been operating between Leipzig and Dresden since 1839. I was shocked that it was in ruins; that it had fallen into such a state of disrepair. As a historian, I found it incomprehensible. Anywhere else, a site like this would have been turned into a museum. What moves me when I think about the deportation of Jews by train is how the history of this technology is intertwined with moral decline – with a descent into barbarism.

Mr Lang, as a member of Dresden’s Jewish community, did you know about the station’s dark past?

Lang: No, and I don’t recall the history of this place being discussed in my youth or even later on. During the GDR era, Alter Leipziger Bahnhof was not recognised as a site of deportations. The subject only came to light in 2001, when the artist Marion Kahnemann – a member of our Jewish community – created a memorial plaque to commemorate deportees at the neighbouring Neustädter Bahnhof.

Do you have any explanation as to why the memory of this place was effectively erased for so long?

Lang: Alter Leipziger Bahnhof continued to operate as a freight station for many years. And there are other memorial sites in Dresden to commemorate the victims of National Socialism. East Germany had already recognised Jews as being a significant victim group. However, the focus was primarily on groups of victims who had actively fought against fascism – my father being one of them.

Here, at Alter Leipziger Bahnhof, we now want to remember the Jewish men and women who were deported to Nazi extermination camps. And we also want to speak about the perpetrators. The deportation of Jews, including those from Dresden’s Hellerberg camp, was organised by the city administration, the police, SS, Gestapo and the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Many people were involved in these crimes.

After the war, the perpetrators and mainstream society in both the Federal Republic and the German Democratic Republic chose to remain silent about this past. When I was at school in East Germany, we never talked about what my classmates’ parents did during the Nazi era. Where were they? Where were they all? After active Nazi criminals were convicted, the GDR quickly declared itself an anti-fascist state. But it failed to address the guilt and the silence of the wider public during the Nazi period – and learn from it.

Holger Knaak und André Lang vor der Ruine des Alten Leipziger Bahnhofs in Dresden | © Andreas Roth

This blind spot is almost palpable at Alter Leipziger Bahnhof: it is a large, forgotten space in the heart of Dresden, overgrown and crumbling. How could this site fade from memory and only be rediscovered in recent years?

Lang: After 1989, a large retail chain acquired a significant portion of the site with plans to build a massive consumer market. This sparked considerable opposition, bringing the old station – and its dark history – back into public focus. In January 2022, we organised a memorial event to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the start of forced deportations. This led to the formation of our supporters’ circle, which is dedicated to establishing a dignified memorial and a space for meaningful encounters.

Mr Knaak, you’re a founding member of the group Gedenkort Alter Leipziger Bahnhof, which was set up in 2024 as an offshoot of the supporters’ association. Why was this project important to you, as the managing director of the blaueFABRIK artists’ collective?

Knaak: I found out more about the station’s dark past when I was preparing for the memorial event in January 2022. It quickly became clear to me that any future use of this large area had to combine existing cultural functions with the building’s past. The old station buildings could be repurposed as exhibition spaces and meeting rooms, a memorial, café and a venue for readings, lectures and concerts.

But there were critical voices from Dresden’s Jewish community, who felt that playing music on the platform ramp, where people were once forced onto trains bound for concentration camps, was totally inappropriate.

Lang: Some members of the Jewish community want this to be solely a memorial site. But some younger voices argue that Jewish life existed before the Third Reich and, thankfully, is flourishing again today. They don’t want to be defined only by the Holocaust. So we met and discussed the matter together. Our goal is to create a place of remembrance, reflection and dialogue between Jews and non-Jews, with events such as discussions, film screenings and musical performances – in keeping with the historical significance of the site. The project will also include a small kosher restaurant or café. It should be a space for interaction between mainstream society and minority communities. In other words, it should be open and welcoming.

What contribution can a cultural organisation like blaueFABRIK make?

Knaak: As more and more people remain in their own bubbles, the need for spaces to bring people together becomes even greater. Art and culture have always had such a function. Many people may feel hesitant about engaging directly with a Jewish community, but as a cultural association, we are neutral territory. We’re an artists’ collective that runs a cultural centre focused on jazz. These themes are relatively new territory for our work, too.

By organising events on these topics alongside our regular programme, we hope to reach people who might not otherwise come into contact with Jewish culture. One example was the event in December with Israeli photographer Idan Golko and Israeli jazz pianist Ido Spak, which was supported by the Goethe-Institut Israel.

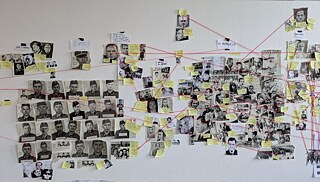

Wandinstallation „The Equation“ des israelischen Künstlers Idan Golko in der Blauen Fabrik | © Idan Golko

Alter Leipziger Bahnhof has been the subject of discussions in Dresden for some years now. When could it realistically open as a place of remembrance and encounter?

Lang: Two years ago, the city council unanimously endorsed this project – albeit with abstentions from the AfD and Freie Wähler. Our association is currently working on an appropriate concept and organisational plan. The total cost is estimated to be around 20 to 25 million euros. We have the support of the Mayor of Dresden and the Minister President of Saxony. A conversation has also taken place with the CEO of Deutsche Bahn, who acknowledged the railway’s shared responsibility for the persecution of Jews. If everyone works really hard, the project could be completed by 2028 or 2029.

Does this plan also reflect the desire not to let death have the final say at this site of deportations?

Knaak: Yes, definitely. National Socialism thrived on the ideology of “us” and “them”, a world view that was not just limited to “Germans” and “Jews”, but also manifested itself in numerous other forms of exclusion. If people today attend concerts, readings or maybe even dance evenings, and Jewish and non-Jewish people enjoy meaningful experiences together, this represents the greatest victory over the Nazis of the past and over those who, even today, regard some groups of people to be more worthy than others. This is an effective way to prevent a divide between Jewish people and others, and more generally, to counter the growing fragmentation of society into isolated groups that can easily be turned against each other.

Lang: This site is also meant to bring people together through culture and music – providing a dignified tribute to the victims of the Shoah. The final message should be: learn from this. So that Jewish life can continue to thrive in our city.

About the people

André Lang (78) is a long-time member of Dresden’s Jewish community and spokesperson for the Förderkreis Alter Leipziger Bahnhof Dresden.

Holger Knaak (47) is managing director of the Dresden-based artists’ collective blaueFABRIK and a historian.

01/2025