European Union

Eurosceptic parties

By PERSPECTIVES NewsroomEurosceptic parties are expected to gain more seats in the next European Parliament

- Can such groups expect an increase in support in your country as well, and if so, why?

The experts' views:

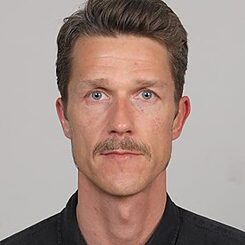

A flag of the EU in front of a building. | Photo: Key Visual 'Survey: Eurosceptic parties' © Markus Spiske for Unsplash

Lithuania

Dr. Ieva Grumbinaitė is a researcher at the Vilnius University Institute of International Relations and Political Science. Ieva‘s academic interests include European integration, EU institutions and decision-making processes, EU higher education policy.- It is unlikely that Eurosceptic parties will do well in the European Parliament election in Lithuania for several reasons. Firstly, Euroscepticism is not a popular sentiment in Lithuania. Opinion polls have consistently shown Lithuanians to be among the Europeans most supportive of the EU and European integration. Secondly, other issues typically represented by Eurosceptic parties that are often on the far right of the political spectrum, such as strict migration policy, anti-LGBT agenda or social conservatism are well covered by the traditional pro-EU center parties in Lithuania. Here one can refer to the strict measures taken against illegal immigration from Belarus by the Homeland Union, or the overall hesitance of the government to pass a law allowing same-sex partnerships. In this context, far-right parties have little unique added value. Finally, the far right in Lithuania is rather fragmented, making it unlikely for any of the small parties carrying some Eurosceptic or EU-critical sentiments to pass the necessary 5% threshold to gain seats in the European Parliament.

Hungary

Tifani Zoé Halmai, studies political sciences at Eötvös Loránd University. She is currently participating in the Perspectives Junior Reporters Program.- In Hungary, eurosceptic parties might indeed anticipate a rise in support, aligning with the broader trend across Europe. Several factors contribute to this potential. In recent years, there has been a strengthening of the nationalist worldview, which favors not an alliance between states but rather national values and sentiments. Freshly, this viewpoint has gained traction in the public consciousness, and as a sort of defense mechanism, euroscepticism has intensified. What does this ideology need to defend itself from? From that, which is somewhat different and is no longer solely the interest of one nation but rather a shared interest, it is a protection from external actors.

- Secondly, a form of skepticism has arisen due to the economic situation; many feel that EU restrictions and policies negatively impact Hungary's economic condition. Eurosceptic parties can capitalize on this voter disillusionment, further solidifying their voter base into skeptics. Additionally, the trend of an aging society does not promote a non-eurosceptic outlook. Indeed, this doesn't mean that every voter will approach the ballot with such thinking. Younger generations, in particular, tend to be more open to the world and to interconnections between nations.

Czech Republic

Martin Nejezchleba is a reporter and editor for DIE ZEIT. In the Leipzig office of the weekly newspaper, he writes about eastern Germany and the centre of Europe. He was born in Czechoslovakia, grew up in Bavaria and worked as a journalist in Prague and Berlin. In 2019 he received the German Reporter Award for his work as well as the German-Czech journalist prize in 2023.- In particular, it is the right-wing populist AfD (Alternative for Germany) that is EU-sceptical in Germany. It is classified as a suspected right-wing extremist movement by the the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, Germany’s federal domestic intelligence agency, and as a “secured extremist movement” in three federal states. One example illustrating AfD’s the far-right positions are the statements made by Maximilian Krah, leading candidate for the EU elections, who openly flirts with historically revisionist and Holocaust-trivialising positions. He recently told the Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica that not all members of the SS, the paramilitary arm of the National Socialist apparatus of extermination and repression, were criminals.

For the EU elections in June, the AfD backed away from its former call for the dissolution of the EU, but Eurosceptic, even anti-European ideas are now clothed in formulas such as the proclaimed goal to build a “Europe of fatherlands”. The EU is portrayed as an all-round failed project, as an “undemocratic construct incapable of reform”.

This party could actually make gains compared to the 2019 EU elections. The question is: by how much? It recently fell from well over 20 per cent at the start of the year to around 15 per cent in the polls for the EU elections. One reason for this is likely to be the nationwide outrage over the so-called Potsdam secret meeting, in which representatives of the AfD and right-wing extremists, among others, discussed the mass deportation of people with a history of migration. It led to an unprecedented wave of protests against the AfD in January. On the other hand, the party is floundering in dealing with ever new revelations about the possible influence from China and Russia. An employee in Maximilian Krah's EU parliamentary office was arrested. He is alleged to be a Chinese spy. Krah and the number two on the electoral list, Petr Bystron, are suspected of having accepted money from Russia. Investigations and house searches burst into the election campaign on a weekly basis. First the party executive committee bans its two top candidates from appearing in the campaign, then they are allowed to appear – only to be sidelined again. The impression on voters: catastrophic. - Why 15 per cent in the polls despite all this? For one, people vote differently in EU elections than in federal or state elections. They don't vote strategically, they give free rein to their frustration, for example with the government in Berlin. On the other hand, the AfD has now built up a solid voter potential that interprets any criticism, even court judgements and investigations, as a kind of electoral influence on the part of “the elites”, “traditional parties” and, as they say, “globalists”. They are receptive to the image that the party paints of the EU, seeing it as a kind of autocratic construct of green and liberal politics to suppress a fantasised will of the people.

This core of voters actually wants the AfD to ridicule and destroy the EU from within. However, the radicalisation of the party could end up undermining its power in Brussels. Following Krah's recent statements on the SS, France’s Ressemblement National and Italy’s Lega Nord announced their intention to force the AfD out of the right-wing ID parliamentary group.

If this should become true, if it is not only pre-election rethorics by Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini, the AfD could enter the European Parliament stronger than ever, more radical than ever – and more powerless then before.

Slovakia

Barbara Zmušková is a Senior Editor at EURACTIV Slovakia, focusing on the rule of law, human rights and economics.- In the current EP term, 6 out of 14 Slovak members of the European Parliament (MEPs) could be classified as Eurosceptic. Two were elected on a ballot of the far right ĽSNS party with a hardline anti-EU platform. Three MEPs, elected on the SMER – SD ballot, were suspended from the S&D Group in 2023. While supporting Slovakia’s membership, anti-EU sentiment is core to SMER – SD, which criticizes and votes against the Green Deal and migration policies. Lastly, the ECR-aligned SaS party ended the term with one MEP, representing its core “Eurorealism” ideology.

- The proportion can rise to 8 out of 15 MEPs in the next term. Three SMER – SD and one SaS MEPs are projected to be joined by one far-right Republika MEP and three MEPs from the SMER – SD defector party, Hlas, whose S&D application was suspended in 2023. As non-inscrits, they will be outside the EP’s day-to-day political work. Hlas politics include Eurosceptic criticism of EU bureaucrats”, migration “quotas”, the Green Deal and rule of law proceedings.

However, the same Eurosceptic tendencies are present in EPP-aligned parties who are projected to win one seat each – KDH and Szövetség. Both parties campaign on a platform of Slovak sovereignty and rally against the EU’s migration and environmental policies.

Poland

Zofia Majchrzak - graduate of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Amsterdam, member of the editorial board of Kultura Liberalna.- There are two eurosceptic political forces in Poland - Law and Justice (PiS) and Confederation. PiS is a former governing party (2015-2023), while Confederation is a coalition of far-right and libertarian fringe groups. None of the parties openly propose that Poland exits the EU. However, some politicians suggested that such an option should be on the table. In the last election to the European Parliament held in 2019, PiS received 45.38% of the vote, winning 27 of 52 seats, while Confederation received 4.55%, winning no seats.

Despite the general expectation that eurosceptic parties across Europe might hold more seats in the next European Parliament, polls predict a drop in the combined score of these two Polish formations in this year's elections. According to the average of polls presented by Politico, PiS could receive 29% and Confederation 10% of the vote. The reason is that PiS's support went down after two terms in power, as Polish voters decided to oust the illiberal government in October 2023. At the same time, Confederation gained some new voters, especially due to exposing a radical free-market agenda. - In the current election campaign both parties portray the European Union as a threat to Poland's sovereignty. They build support mainly around a harsh criticism of the European Green Deal. According to their narrative, the EU policies will increase the cost of living and constitute a threat to the freedom and financial prosperity of Poles. They firmly oppose a deeper EU integration.

These slogans had a clear influence on the public sphere. We have seen considerable public support for the recent farmers' strikes against the European Green Deal. Also, the other mainstream parties changed their rhetoric, in order to incorporate selected eurosceptic tropes. However, support for eurosceptic parties is significantly lower than it was five years ago. All in all, the eurosceptic parties in Poland will likely receive less seats in the European Parliament but their ideas and policies have a strong effect on the national political scene.

Lithuania

Vladas Gaidys is a sociologist and the head of the public opinion and market research company “Vilmorus.” His research focuses on public opinion, social trends, and societal attitudes in Lithuania.- In contemplating the electoral prospects of eurosceptic forces in Lithuania, sociologist Vladas Gaidys sheds light on the country's political landscape. While some nationalist-leaning groups harbor eurosceptic sentiments, they struggle to secure significant parliamentary presence, partly due to the influence of figures like Vytautas Landsbergis. Russian-speaking minorities may also hold eurosceptic views, but their numbers are limited. Despite occasional protests, Lithuania's overall optimism towards the EU prevails, buoyed by newfound freedoms like working and studying abroad. Critiques of the EU's slow decision-making contrast with economic optimism but don't translate into eurosceptic gains. The National Union may have limited prospects, while the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, critiquing EU agricultural policies, could secure representation. In essence, while eurosceptic voices exist, Lithuania's societal optimism towards the EU, driven by newfound freedoms and economic prospects, dampens their electoral potential.

Czech Republic

Miloš Gregor is an advisor to the prime minister on information literacy and countering disinformation.- Turbulent times tend to mean a sharpening of political competition. The extreme poles of the political spectrum tend to benefit. It is the case today, after the COVID-19 pandemic and at the time of Russia's war against Ukraine and related crises. It is logical that citizens have many concerns and populists offer simple, but unfortunately mostly unrealistic solutions to them. We have seen this in the past many times. What is new, however, is the considerable overlap between the program and the rhetoric of Euroskeptics, populists, extremists and anti-system subjects. It would be unfortunate to equate these political trends and styles, but at the same time it would be an alibi to ignore the links between them.

- The second important factor is a series of myths, half-truths, mis- and disinformation or outright lies circulating in the information space in member states. Thematically, they range from innocent jokes to the propaganda of hostile powers. What they have in common, however, is that they explicitly or implicitly undermine citizens' trust in the European Union. If society is more exposed to them, support for Eurosceptic parties logically increases. It is clear from the above that this year's elections are taking place at a time when several factors play into the hands of the Eurosceptics. Therefore, it is not only up to the other political parties, but to all of us who speak in public to remind citizens of the benefits of the EU.

Denmark

Jorgen Samso is an award-winning Danish journalist, producer and correspondent based between Copenhagen and Belgrade. He has covered stories all over the world for a wide range of international media outlets. He holds an M.A. in Journalism, Politics & International Affairs from Columbia University, New York, and is a 2024 Perspectives Journalist-in-Residence at the Goethe Institute in Prague.- Opinion polls in Denmark predict voters will follow suit in confirming the Europe wide expectation of a rightwing turn in the upcoming EP elections. On the forefront in emphasizing this swing as a fait accompli is current MEP Anders Primdahl Vistisen, front runner for the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti) belonging to the political EP-family, Identity and Democracy (ID). He is predicting “a landslide victory” for the European right wing, also in Denmark, on June 9.

Vistisen, along with other Danish rightwing parties, is stoking the same fears as other right-wing parties across Europe: the threats of mass migration, the hazardous economic effects of climate change policies on the common man and ‘an oversized EU bureaucracy’. Vistisen recently hammered away at the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, promising to lay off 10.000 employees in the EU system. “And the first one to go will be you, Ursula von der Leyen,” he said from the podium a political event in Maastricht. Von der Leyen was standing right next to him. - With the rightwing wheels seemingly in full motion across Europe, the question is how national political sentiments will translate into EP-voter behavior?

The popularity of the current Danish bipartisan-government is dropping drastically. “The Russian assembly lines are running 24/7,” PM Mette Frederiksen recently said. “The Russians are not taking time off, they keep working,” she continued, in a bid to calm down angered Danish voters who recently saw a public national holiday annulled. Analysts say, this disappointment could lead voters to “punish” the current government and be more prone to vote at margins of the political spectrum on June 9.

Never mind the – perhaps – sound reasons behind upping Danish productivity, voters still seem unconvinced on the national level and half of them are still undecided about how to vote in EP elections, according to the latest polls. Left, right or center – the fait accompli of a landslide swing to the right in Denmark might still be up in air.