German Colonialism in China More than Just Kiaochow Bay: A (Nearly) Forgotten Story

Old colonial building in the Deutsche Straße (German Street) in Qingdao (Tsingtau), capital of the former German colony Kiautschou. Qingdao was the only German colony in the Far East. Even today, the Chinese metropolis of millions shows traces of the German colonial period. | Photo (detail): Christoph Mohr © picture alliance

Iltisstraße, Berlin-Dahlem: In German, the word “Iltis” means “polecat”, evoking that little native carnivore from the marten family after which the road must surely have been named. But actually it wasn’t at all – to this day the street name commemorates a chapter in the history of German colonialism.

Along with neighbouring streets Lansstraße and Takustraße, it was originally supposed to honour the successful attack on the Taku Forts (Dagu Forts) carried out by the Iltis, a German torpedo boat commanded by Captain Lans; the forts were meant to prevent access to the large port of Tianjin – and therefore bar the way to Peking. The attack was the start of the Colonial War in 1900/1901, the first of many bloody battles fought by German and Allied troops against the Chinese Empire, and a climax in the aggression practised by the imperial forces.By concluding the Sino-German Unequal Treaty of 1861, Prussia as vanguard of the German nations had also joined the phalanx of imperial forces that had served to massively restrict China’s territorial, political, financial and economic sovereignty since the First Opium War in 1840-42, rendering the country an informal colony. In the Second Opium War from 1858-60 these semi-colonial structures were reinforced and extended. The most profitable trading commodity was opium. The fact that it was a drug with catastrophic consequences for individuals and for the whole country was played down. According to the new treaties, it was now possible to import opium – the same as all the other goods – at giveaway prices.

The country’s economic and financial structure was destroyed, and China was forced to borrow large sums on credit in order to pay off the huge reparations to the imperial powers. Large swathes of the population sank into poverty, resulting in uprisings – against the foreign aggressors and their representatives as well as against the Qing regime, which was unable to stop the country from being exploited and bled dry financially. Prussia, from 1871 the German Empire, had been profiting from the economic advantages of the semi-colonial system since 1865, and was already lining up its naval ships that were patrolling the coast ready to be deployed locally in the ports, or threatening to.

However Germany was by no means in a position to enforce the acquisition of a territorial colony similar to Britain’s Hong Kong, as had been their ambition since the 1870s, because of the determined resistance put up by the Chinese government. However the experts furnished themselves with the necessary diplomatic, linguistic and cultural knowledge necessary for further expansion, and with the foundation of the Seminar for Oriental Languages in Berlin in 1887 the systematic generation of knowledge required for colonial expansion began for China too.

“Coal station and naval base” – those are two further misleading terms that were used in 1897-98 by German diplomats in negotiation with the Chinese government, after German troops had occupied an area in Jiaozhou Bay and its port Qingdao. After long negotiations and with the threat of further military aggression, the Empire obtained a 99-year lease on the region through extortion, and it was known as the “Kiaochow Bay Leased Territory”. Identifying the colony as a “leased territory” was the sole achievement of the Chinese negotiators. But whatever the area was called in the following decades and sometimes even still, a “protectorate” or “model colony”, it was a de facto German colony from 1897 to 1914 as well as part of Shandong Province, as a fortification of that same direct German “sphere of influence” with economic and military privileges.

As with all territorial colonies they implemented a spatial and socio-cultural segregation for the rulers and the ruled, inequality was reproduced and the specifically colonial instruments of government became established: first of all the complete suspension of the sovereign rights of the Chinese state, the aggressive military attitude of the troops, and quashing of the slightest resistance, including what was known as penal expeditions, particularly in the early days. Subsequently they imposed expropriation and dispossession measures on the rural and urban population, restricted Chinese trading activities, abrogated the Chinese social and legal systems and developed a new two-part legal system, as well as banning the Chinese from settling in what was termed the “European Quarter”.

The fact that from around 1904 the Germans were very committed to what they called Germany’s Cultural Mission and less focused on the military was because of the realisation that that was the only way the German Reich could profit from China in the long term.

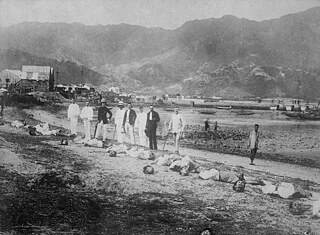

Of course there was resistance against the colonial rulers as well: while mainly the social stratum comprising public servants and academics went all-out to demand political reforms albeit without success, and the merchant classes were increasingly managing to assert their economic interests, the uneducated rural population, anticipating their cultural order to be primarily under threat from foreign missionaries, also put up resistance through campaigns of violence – culminating in the Boxer Rebellion and the Colonial War that followed it in 1900-01. The German Reich played a part in this war as well as profiting from it: they had military command over the troops dispatched by the eight Allied nations, they pocketed most of the reparation money China had to pay, and finally they were responsible for a series of violent acts and so-called penal campaigns against the rebellious boxers and the population.

The fact that from around 1904 the Germans were very committed to what they called Germany’s Cultural Mission and less focused on the military was because of the realisation that that was the only way the German Reich could profit from China in the long term. And the fact that a modern urban infrastructure and traffic system with medical and educational facilities (military hospitals, clinics, schools, an observatory, the Sino-German University) had been developed in the European Quarter in Kiaochow Bay, which were also used by some of the Chinese population, also had a propaganda effect: the colonial project was supposed to demonstrate civilisation, progress and modernity for the benefit of the Chinese people as well as the international British rivals. That offers points of connection right up to the present day with regard to the origins and perpetuation of the narratives of modernisation, in German as well as to some extent Chinese historiography.

In the triangle formed between Iltisstraße, Takustraße and Lansstraße in Berlin-Dahlem, after much campaigning by residents, they put up an information board in 2011 detailing their colonial origins. Kiautschou-Straße in Berlin-Wedding on the other hand still bears no reference to its historical background. The German colonial project in China has no place in the cultural memory of most Germans, or it’s associated with the concept of “model colony” and modernisation.

You can learn more about German colonialism in China from this interview with Qingdao city historian Zhu Yijie:

0 Comments