Black German Literature Asking the Right Questions

Being Black should be completely unremarkable in today’s multicultural Germany. Yet many people still struggle with everyday discrimination and sometimes even blatant racism. Their stories are increasingly finding their way into German literature.

The 2020 Festival of German-Language Literature in Klagenfurt kicked off with a speech on Black art and against racism. The Ingeborg Bachmann Prize for outstanding prose is awarded annually at the festival, and the 2016 winner, author Sharon Dodua Otoo, was the first Black, female author to give the opening address.

The German literary scene has seen a whole series of other successes by Black writers since Otoo was honoured in 2016. Some of her novels have been released by major publishing houses and enjoy wide readership. Olivia Wenzel’s debut 1000 serpentinen angst (1000 Serpentines of Fear) was nominated for the 2020 German Book Prize, and Jackie Thomae’s novel Brüder (Brothers) has also received considerable attention. The Spiegel bestseller lists have been and continue to be topped by works of Black German female authors: Florence Brokowski-Shekete’s autobiography Mist, die versteht mich ja! Aus dem Leben einer Schwarzen Deutschen (Crap, she understands me! Excerpts from the life of a Black German woman), Tupoka Ogette’s Exit Racism – Rassismuskritisch denken lernen (Exit Racism – Learning to Think Critically about Race), Alice Haster’s Was weiße Menschen nicht über Rassismus hören wollen, aber wissen sollten (What White People Don’t Want to Hear about Racism, But Should Know), and finally Sharon Dodua Otoo’s novel Adas Raum (Ada’s Room).

Author Tupoka Ogette was honoured in the “Idol of the Year” category at the 2021 “About You” Awards.

| Photo (detail): picture alliance/dpa/Henning Kaiser

These books exemplify the issues Black German authors explore in their writing, with racism and the forms of discrimination associated with it still heading the list. Additionally, authors critically look at the threat to life and limb presented by neo-Nazis, racism in the family, inadequate psycho-social care due to ignorance of Black people’s living situations, discrimination on the housing market, stereotypical attributes uncritically adopted from the German colonial era, and the everyday disregard for personal boundaries. Still, the fact that these books exposing individual and structural racism are getting noticed, and that some of the answers are being provided by Black people – even if the questions still seem socially predetermined – is a fairly recent innovation.

Author Tupoka Ogette was honoured in the “Idol of the Year” category at the 2021 “About You” Awards.

| Photo (detail): picture alliance/dpa/Henning Kaiser

These books exemplify the issues Black German authors explore in their writing, with racism and the forms of discrimination associated with it still heading the list. Additionally, authors critically look at the threat to life and limb presented by neo-Nazis, racism in the family, inadequate psycho-social care due to ignorance of Black people’s living situations, discrimination on the housing market, stereotypical attributes uncritically adopted from the German colonial era, and the everyday disregard for personal boundaries. Still, the fact that these books exposing individual and structural racism are getting noticed, and that some of the answers are being provided by Black people – even if the questions still seem socially predetermined – is a fairly recent innovation.

Where Are You Really From?

Adas Raum links the beginnings of colonialism at the end of the 15th century with 21st century Berlin via reincarnations of protagonist Ada. As in her Bachmann Prize winning short story, in Adas Raum, Otoo again employs objects as equal narrators. Olivia Wenzel explores the life of her first-person narrator, who grows up in East Germany and is socialised in the united Germany of the 1990s, dialogically: sometimes questions directed at the first-person narrator by a person offstage determine (or disrupt) the flow of the narrative, and conversely the first-person narrator’s questions to a person offstage change events. These are dialogues on the self and society that highlight some aspects of being Black in Germany. They speak to the perpetual questioning of a Black person’s German identity, of omnipresent racism and a deep sense of insecurity.

Florence Brokowski-Shekete’s autobiography, Mist, die versteht mich ja!, on sale since autumn 2020, tells the story of a woman who succeeds in becoming the first Black female school district superintendent in Germany. The book begins with the question that runs through all the biographies of Black people in Germany – “Where are you really from?” and the implicit implication that a Black person cannot possibly be truly German. Like earlier autobiographies written by Black Germans, the book counters this question with its own perspective, showcasing the resilience and strength required to overcome the hurdles this attitude creates.

The Eternal Question of What It Means to Be German

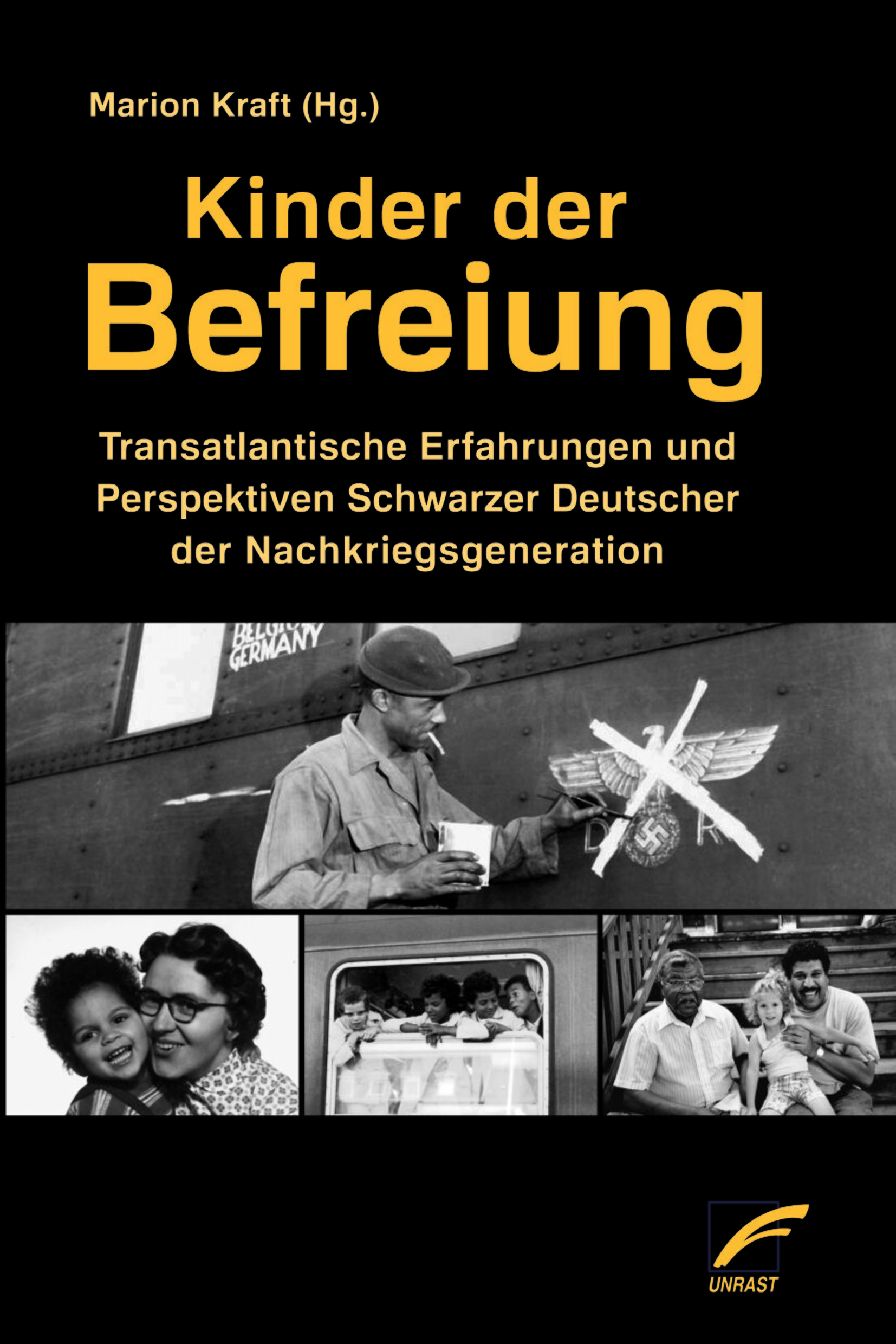

In the “Kinder der Befreiung” (Children of the Liberation) anthology published by Marion Kraft, those affected report on their lives and experiences in post-war Germany.

| Photo: © Unrast Verlag

Black literature in Germany has long tried to convey that it is not only possible to be Black and be German, but also perfectly normal, despite persisting views to the contrary. The Farbe bekennen (Showing One’s True Colours, 1986) documentary book by poet May Ayim describes a debate from the early 1950s when the children white German women had with African-American men immediately after the end of WWII were about to start school. The German Federal Republic even debated how to deal with these children as high as the Bundestag level, and seriously considered sending them “to the homeland of their fathers.” Those involved tell their stories in Kinder der Befreiung (Children of the Liberation, 2015). The theme continued into the 1990s: In her autobiography Kind Nr. 95 (Child No. 95, 2009), Lucia Engombes describes how she was brought to the GDR in the 1970s as a child of SWAPO fighters, where she grew up and was then deported to Namibia, a country almost completely unknown to her, after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In the “Kinder der Befreiung” (Children of the Liberation) anthology published by Marion Kraft, those affected report on their lives and experiences in post-war Germany.

| Photo: © Unrast Verlag

Black literature in Germany has long tried to convey that it is not only possible to be Black and be German, but also perfectly normal, despite persisting views to the contrary. The Farbe bekennen (Showing One’s True Colours, 1986) documentary book by poet May Ayim describes a debate from the early 1950s when the children white German women had with African-American men immediately after the end of WWII were about to start school. The German Federal Republic even debated how to deal with these children as high as the Bundestag level, and seriously considered sending them “to the homeland of their fathers.” Those involved tell their stories in Kinder der Befreiung (Children of the Liberation, 2015). The theme continued into the 1990s: In her autobiography Kind Nr. 95 (Child No. 95, 2009), Lucia Engombes describes how she was brought to the GDR in the 1970s as a child of SWAPO fighters, where she grew up and was then deported to Namibia, a country almost completely unknown to her, after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Biographical works explore the impact of being repeatedly confronted with the question of what it means to be German on Black people in Germany especially poignantly. As the title of the autobiography by recently deceased Holocaust survivor Theodor Wonja Michael, Deutsch Sein und Schwarz dazu (Being German and also Black, 2013) alludes to, and also described in the autobiography by Ika Hügel-Marshall in Daheim unterwegs – Ein deutsches Leben (Out and About at Home – A German Life) first published in 1998, being Black and German has long required fighting back against considerable resistance.

Perhaps this is why Black literature in Germany is currently insistently demanding that our society finds and lives out contemporary answers to questions of identity. Answers to the questions of who we are, who we want to be, and what it means to be German in a society that has undergone profound demographic, political, cultural, and literary changes since World War II.

0 Comments