Hannah Arendt Thinking is Dangerous

“Hannah Arendt: Thinking is Dangerous” explores Hannah Arendt’s conception of thinking through dialogue, art, performance, play, music, and silence. Artists, poets, writers, scholars, musicians, and activists who think with Hannah Arendt as they explore questions of solitude, peace, privacy, freedom, friendship, and politics today.

“There are no dangerous thoughts for the simple reason that thinking itself is such a dangerous enterprise,” Hannah Arendt said in her final interview with the French author Roger Errera on French national television. Errera was asking Arendt what the 20th century might leave to the 21st by way of remembrance. And Arendt, in her usual fashion, turns the question around to discuss how “our inheritance has been left to us by no testament”, quoting the French poet, René Char.Arendt was not presumptuous enough to include her work among those things which might be passed on from one century to the next, but she was well aware of the phenomenon of posthumous fame. Though, it is possible, having gained a certain amount of fame in her own lifetime, she discounted herself from this fate. And yet, Arendt has become one of the most famous political thinkers of the 20th century, and now 21st. According to her literary estate, today her books are selling thirty-fold.

When Arendt died in 1975, she was mostly known for her reportage on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Hitler’s logistical mastermind. But when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016 something shifted. Arendt’s 1951 masterpiece The Origins of Totalitarianism became a bestseller. As people began to try to understand what was happening in American politics they reached for her work from the mid-20th century to think about the world today.

The Origins of Totalitarianism was published in 1951, the same year Arendt received American citizenship after being a stateless refugee for nearly twenty years. The book, which is really three books in one – antisemitism, imperialism, and totalitarianism – documents the emergence of totalitarianism in the middle of the 20th century as a radically new form of government, grounded in the existential conditions of homelessness, rootlessness, and loneliness. She traces the elements that crystalized in the phenomenal appearances of Hitlerism and Bolshevism through the rise of the nation-state, the twin forces of imperialism and colonialism, and the collapse of the political, which gave rise to mass politics through ideology, propaganda, and unthinkable violence. It is an epic work.

But who was Hannah Arendt?

And can her work help us to understand the human condition in the 21st century?Arendt dedicated her life to understanding the most pressing political questions of the 20th century: the emergence of totalitarianism, the politics of revolution, the loss of the freedom, the triumph of the social, the rise of mass loneliness, and the problem of evil.

But Arendt did not start out as a writer. She became a writer by accident when she was forced to abandon her academic career in 1933 and flee Nazi Germany after being arrested at the Prussian State Library and detained by the Gestapo for eight days. At the age of 27 she made her way through Prague to Geneva to Paris where she learned French, Hebrew, and Yiddish, while working to help Jewish youth prepare for emigration to Palestine.

Evil comes from a failure to think

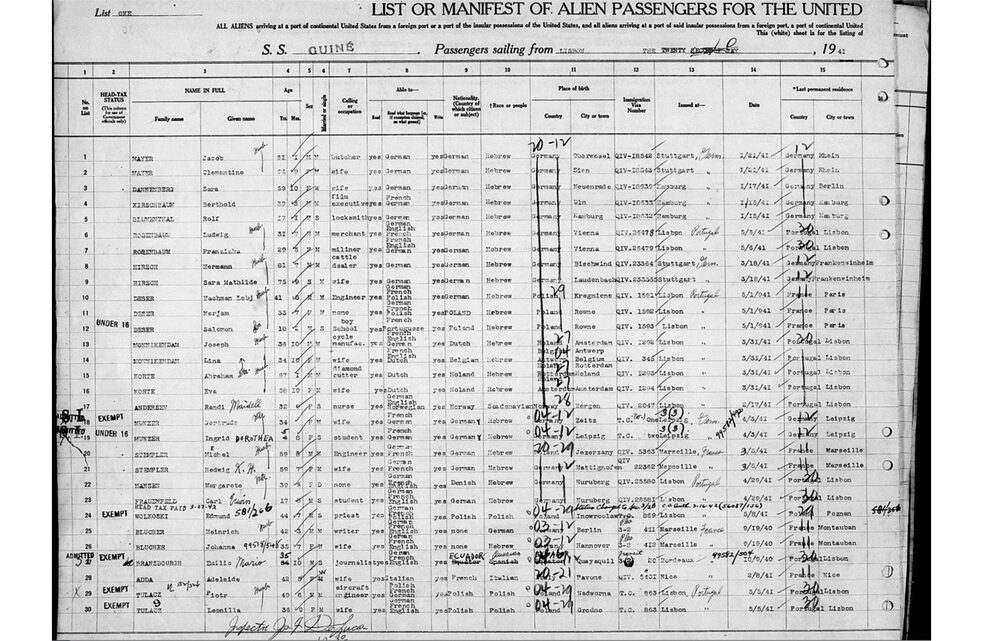

After escaping a French internment camp in the summer of 1940 with 62 other women, Arendt was able to secure exit papers with the help of Varian Fry and arrived in New York City on 22nd May 1941 with her husband Heinrich Blücher. As she began her new life, she worked as a housekeeper, editor, journalist, and adjunct professor all while beginning to write The Origins of Totalitarianism.More than anything, Arendt wanted to understand. At core, her work is not about what to think, but how to think. She turned away from the world of “professional thinking” in 1933 to become a writer, because she was horrified by the Gleischschaltung, or political coordination of her peers. Unlike many of her friends and colleagues, she was attuned to what was happening in Germany as early as 1929. And when she saw the burning of the Reichstag on 27th February 1933, she knew she had to act. Many years later in an interview with Günther Gaus when asked what caused her to turn to the political she said: “From that moment on I felt responsible. That is, I was no longer of the opinion that one can simply be a bystander.”

In Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship, Arendt argues that the difference between people who went along with the Nazification of Europe’s social, political, education, and cultural institutions was thinking. Evil, she argued, comes from a failure to think.

One claim at the heart of Arendt’s work is that the dialogue of thinking might open up a space where we can call the conscience – the moral self – into question, and therefore prevent evil. Thinking prepares us for judgment, and shapes the way we are in the world. Following Plato, she argued that since evil is not a virtue, it cannot be thought. Therefore, evil is unthinking. And this means that everyone has a duty to think. She writes: “If the ability to tell right from wrong should turn out to have anything to do with the ability to think, then we must be able to ’demand’ its exercise from every sane person, no matter how erudite or ignorant, intelligent or stupid, he may happen to be.” Thinking does not belong to some rarified world of professional thought, and indeed thinking removed from the world, can turn people away from what is unfolding right in front of them.

0 Comments