Fact-checks Pinocchio for President

What’s true, and what’s a lie? Many an outrageous report on the internet has subsequently turned out to be pure invention. For this reason fact-checkers, who verify information, have a key role to play in the age of social media. We take a look at the opportunities and limitations of exposing fake news.

It was through little Pinocchios that many people encountered fact-checks for the first time: in 2011 American journalist Glenn Kessler from the Washington Post started scrutinising the facts in politicians’ speeches. The editorial team started to add small Pinocchio images to the fact-check articles to make ratings like “partly correct” or “mostly false” easier to understand. The more Pinocchios with their long lying noses, the more mistakes and false claims they had found.

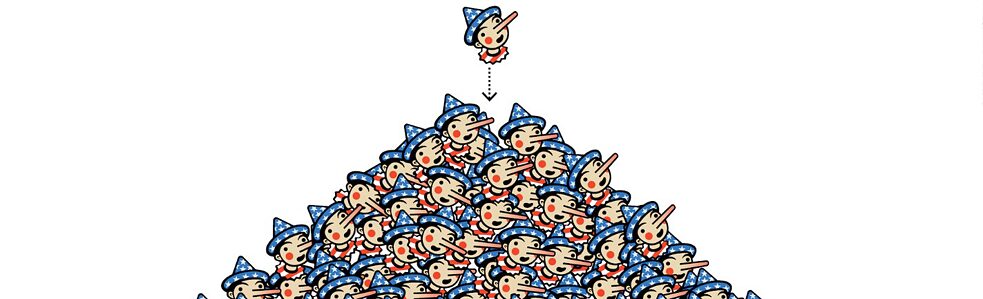

The concept became increasingly well-known in 2016, during the Donald Trump election campaign in the US. Trump himself openly joked that he needed to watch what he said to ensure he didn’t get even more Pinocchios from the Washington Post. His statements repeatedly fell into the “Bottomless Pinocchio” category at the Washington Post editing office. This denotes false statements that have been repeated over 20 times, meaning there’s an assumption of deliberate disinformation.

The “Bottomless Pinocchio” rating category introduced by the Washington Post in 2018 is awarded by the editorial team when politicians repeat a false claim more than 20 times. This honour was bestowed upon Donald Trump many times.

| Photo (detail): © Screenshot Washington Post/Steve McCracken

During the US election campaign, an increasing number of media companies worldwide were setting up in-house teams with the specific goal of tracking down false information – known as disinformation – on the internet and using fact-check articles to expose and debunk these untruths. It didn’t take long for the fake news spreaders themselves to seize the moment and adorn themselves with the non-copyright title of “fact-checker”. This gave rise to confusion and called the credibility of fact-checking per se into question.

The “Bottomless Pinocchio” rating category introduced by the Washington Post in 2018 is awarded by the editorial team when politicians repeat a false claim more than 20 times. This honour was bestowed upon Donald Trump many times.

| Photo (detail): © Screenshot Washington Post/Steve McCracken

During the US election campaign, an increasing number of media companies worldwide were setting up in-house teams with the specific goal of tracking down false information – known as disinformation – on the internet and using fact-check articles to expose and debunk these untruths. It didn’t take long for the fake news spreaders themselves to seize the moment and adorn themselves with the non-copyright title of “fact-checker”. This gave rise to confusion and called the credibility of fact-checking per se into question.

The Poynter Institute for Media Studies in America identified the problem and in 2015 founded the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), in which 121 fact-checking organisations are currently committed to a shared code of principles. They are assessed annually to ensure compliance with criteria such as party-political independence, transparent research and financial disclosure. If a fact-check edit carries the IFCN quality seal, then it’s highly likely to be genuine. The seal is especially helpful to readers looking for trustworthy sources in countries where they are not familiar with the media scene, or do not speak the local language. An up-to-date list of signatories can be found online here.

Too Few Fact-Checkers for all the Fakes

But what reach are the fact-check teams achieving with their research? Media organisations generally publish their fact-check articles on their own websites and therefore target their existing readerships. But that isn’t necessarily the people who have been duped by the fakes. The thing is, disinformation is spread in particular via platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, YouTube etc. For this reason it’s a good idea to verify facts in those places too.

After significant political pressure, almost all of the major platforms have now started up appropriate programmes and are collaborating with fact-checkers. As a rule, the requirement is that the fact-checking organisation concerned is a member of IFCN. But ultimately only the companies themselves know how many people are being reached by the fact-checks on the platforms. Data access for independent research has been systematically restricted by the platforms in past years. This lack of transparency is a fundamental problem.

However the platforms themselves admit that there are nowhere near enough fact-checkers to verify all the fakes. That was why back in 2018 Facebook formulated the goal of using artificial intelligence to try and close this gap even further. A number of fact-checking organisations are already working on automated approaches themselves, to enable them to check more content within a shorter timeframe or reach a wider audience with fact-checks. Some tools are already being used in practice. For example in 2020 the German fact-checking team from the Correctiv research centre launched their WhatsApp chatbot. Readers can submit images, videos or voice messages to this tool if there is suspicion that they are based on false information. If the bot finds a relevant fact-check in the archive, the information is automatically sent back in response.

Can Artificial Intelligence Expose Disinformation?

A number of organisations discussed the current situation regarding support from artificial intelligence at an international fact-checking conference in June 2022 in Oslo. There are now options to automate almost all aspects of the fact-checking process. However most of these tools have so far not been available to the public. In this context, Kate Wilkinson from British fact-checking group FullFact and Pablo Fernández from the Argentine organisation Chequeado discussed a tool they had developed to search websites for factual claims (these are the only kind that can be fact-checked) and then use artificial intelligence to search specifically for relevant statistics to check these claims. Bill Adair from the American fact-check project shared details of a new tool development designed to enable automatic live fact-checking of videos. To do this, the tool performs real-time claim detection on videos and shows exact matches with fact-checks from a database.

So is it just a matter of time until fact-checkers become superfluous? That’s not the way things are looking at the moment. Firstly the tools are not error-free, for example incorrect language translations have been generated. And secondly, well-informed evaluations are often complicated and cannot be simply compartmentalised into either “fake” or “not fake”.

The tools can certainly detect that a photo has been used for false claims in the past, for instance, and mark it as disinformation. However this approach also leads to false positives. After all, some people are also sharing the image to make others aware of the fake. In other instances, text has been added to make the satire or irony clear. Subtleties like this present a problem for automated fact-checking.

Furthermore: right from the outset the main platforms have been focusing on fact-checking for markets within the Global North – and the likely reason for that is because that’s primarily where regulations were posing a threat. There have been no efforts to implement fact-checking for a wide range of languages in Global South countries. The development of automated tools is predominantly happening in European languages like English at the moment as well.

So fact-checkers will continue to be centrally positioned in the campaign against disinformation. Although automated tools can accelerate the fact-checking process hugely, the Pinocchios are still being awarded by people.

Another factor is that almost all large-scale fact-check organisations also rely on media literacy. Ultimately disinformation can only spread effectively on a large scale if lots of people fall for it. In the long term even the best tools won’t be able to solve this problem. There’s only one way: everyone should be in a position to apply basic journalistic verification techniques themselves. For example – knowing the criteria for legitimate sources and being able to verify images, videos and claims on the internet. To achieve this, we need comprehensive media education that targets the whole of society.

0 0 Comments