Encyclopaedias Memories of Brockhaus

Which of you now aged 40-plus no longer remembers those hefty volumes on your parents’ bookshelves: encyclopaedias like “Brockhaus” were the epitome of education and knowledge per se – until the internet and Wikipedia heralded the end of an era.

My grandfather loved crosswords. He himself only subscribed to the TV guide Hörzu, but everyone who knew about his passion brought him selected magazines, or neatly separated the puzzle pages out of the papers. And I looked forward to the holidays, when we used to sit together on the sofa with an atlas and of course an encyclopaedia on the table in front of us.

My grandfather was a car mechanic, and it would never have occurred to him to put a multivolume encyclopaedia on his bookshelf. His books included a thick, single-volume reference work with black-and-white illustrations, a generic publication that – like almost the entire contents of my grandparents’ very compact library – originated from the book club, of which millions of Germans were members in the 1950s and 1960s. This enabled them to receive books on a quarterly basis, usually bestsellers at a cheap price. The one-volume reference book was still on the shelf, well-thumbed and in a protective plastic sleeve, when his home was cleared out after my grandfather’s death.

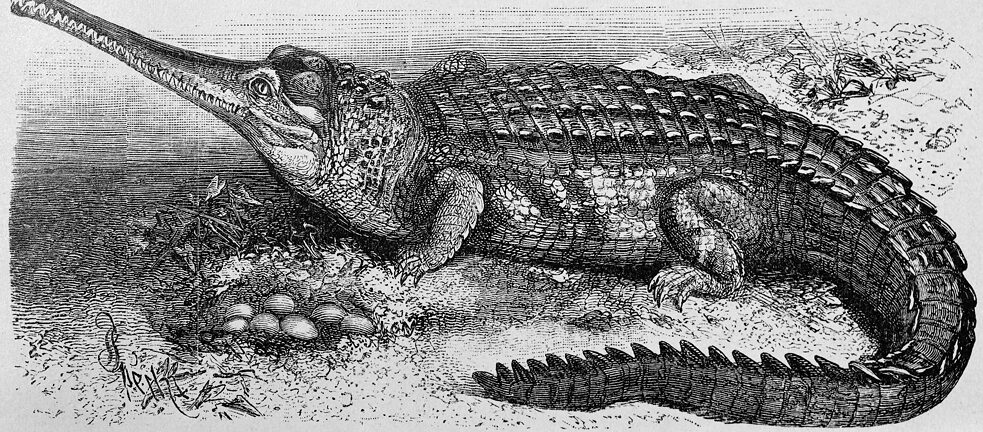

The Brockhaus was full of vivid illustrations to provide knowledge-hungry readers with a visual impression as well. Here’s a picture of a crocodile from the 1908 edition.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/imageBROKE/Karl F. Schöfmann

The Brockhaus was full of vivid illustrations to provide knowledge-hungry readers with a visual impression as well. Here’s a picture of a crocodile from the 1908 edition.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/imageBROKE/Karl F. Schöfmann

“Look It Up in the Brockhaus!”

There was hardly a household in Germany without at least one encyclopaedia – in addition to the Bible, which almost everyone had too. Not many people had a multi-volume encyclopaedia, and if you had five, ten or even twenty volumes in the living room it labelled you as a member of the educated classes, generally an academic – and this certainly included the nouveau riche in some cases. It was when visiting a school friend who grew up in a detached house that I saw my first “Brockhaus”. It was kept in a teak bookcase beside the piano, and when I came round to play in the afternoons you could be sure that one of those mighty tomes would be on the table alongside the homework.

You didn’t just call the “Brockhaus” an “encyclopaedia”. All the other reference works were called that, no one said “Why don’t you look it up in the Knaurs!” or “I’m sure you’ll find that in the Mayer”. But rather like the “Duden” dictionary, the “Brockhaus” was considered the ultimate reference, it wasn’t simply an encyclopaedia, it was THE encyclopaedia, you might say it was the Mercedes of encyclopaedias. It was the German counterpart to the big encyclopaedias published by our European neighbours. The French reference work Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers is considered to be the origin of the encyclopaedic concept. Its 35 volumes were published under the editorship of Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert between 1751 and 1780. It contained around 70,000 entries written by leading scholars of the time. The Encyclopædia Britannica, which was published a few years later (1768 onwards), is also centred on the opinion prevalent in the Age of Enlightenment – that the entirety of human knowledge should be summarised as comprehensively as possible and presented in a format that can be understood by all. The Britannica was considered the cornerstone of knowledge throughout the English-speaking world right into the early years of the 21st century – and the advertising slogan “When in doubt, look it up. The sum of human knowledge” was not doubted by anyone.

World knowledge on your bookshelf

His name is on everyone’s lips – but what did he actually look like, the father of all encyclopaedias? May we introduce Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (1772–1823).

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / akg-images

In German-speaking countries the first publication to put the encyclopaedia concept into practice was Conversationslexikon mit vorzüglicher Rücksicht auf die gegenwärtigen Zeiten, under the editorship of Renatus Gotthelf Löbel and Christian Wilhelm Franke, whose six volumes were published between 1796 and 1806. But then in 1808 Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (1772–1823) entered the picture, when he bought up the publication rights and the entire inventory of the Löbel-Franke encyclopaedia at the Leipzig Book Fair and commissioned further volumes. By 1811 Brockhaus had managed to sell all of just 2,000 copies of the Conversation Lexicon that were published in the first edition. When F. A. Brockhaus died in 1823, not only had he secured a number of university professors as content providers, but he had also established the business model for supplementary volumes on an ongoing basis. You see, one thing those early encyclopaedists hadn’t anticipated was the rampant development of the sciences. The encyclopaedia, which was meant to depict a current state, needed to be reviewed constantly. For this reason many articles had to be written from scratch, edited or revised from one edition to the next. Specialist publishing houses emerged in all the European countries, each with the business principle of pooling and sharing knowledge in book format. The most important premise for successful sales was absolute confidence in the correctness of the information. The “Brockhaus”, as the authoritative German reference work had been known for short since the 17th edition, represented precisely this respectability. Anyone who could afford to invest in all these volumes was able to rest assured that they would have the world’s available knowledge right there on the bookshelf for many years – a whole lifetime even.

His name is on everyone’s lips – but what did he actually look like, the father of all encyclopaedias? May we introduce Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (1772–1823).

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / akg-images

In German-speaking countries the first publication to put the encyclopaedia concept into practice was Conversationslexikon mit vorzüglicher Rücksicht auf die gegenwärtigen Zeiten, under the editorship of Renatus Gotthelf Löbel and Christian Wilhelm Franke, whose six volumes were published between 1796 and 1806. But then in 1808 Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (1772–1823) entered the picture, when he bought up the publication rights and the entire inventory of the Löbel-Franke encyclopaedia at the Leipzig Book Fair and commissioned further volumes. By 1811 Brockhaus had managed to sell all of just 2,000 copies of the Conversation Lexicon that were published in the first edition. When F. A. Brockhaus died in 1823, not only had he secured a number of university professors as content providers, but he had also established the business model for supplementary volumes on an ongoing basis. You see, one thing those early encyclopaedists hadn’t anticipated was the rampant development of the sciences. The encyclopaedia, which was meant to depict a current state, needed to be reviewed constantly. For this reason many articles had to be written from scratch, edited or revised from one edition to the next. Specialist publishing houses emerged in all the European countries, each with the business principle of pooling and sharing knowledge in book format. The most important premise for successful sales was absolute confidence in the correctness of the information. The “Brockhaus”, as the authoritative German reference work had been known for short since the 17th edition, represented precisely this respectability. Anyone who could afford to invest in all these volumes was able to rest assured that they would have the world’s available knowledge right there on the bookshelf for many years – a whole lifetime even.

The End of an Era

I received my first encyclopaedia, like many others born in the 1950s and 1960s, at my confirmation. Of course the ten volumes bound in synthetic leather didn’t come from Brockhaus, nevertheless I was proud of them and placed them right at the top of my bookshelf. Now I – the first in my family to attend a Gymnasium – had almost become a member of the educated middle classes. Alongside the Duden, the encyclopaedia was an essential reference work for plenty of projects and homework assignments, but at the same time it was also a symbol of social advancement through education, in which the majority of the non-academic population firmly believed. As late as 1980, just 17 per cent of a school year group achieved the Abitur.

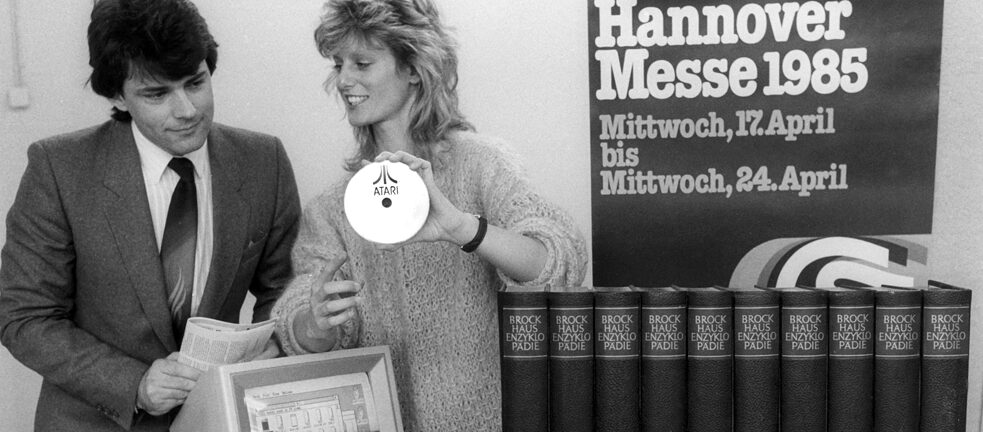

The Brockhaus on a journey into a new era: in 1985 the reference work was available on CD-ROM for the first time.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/Wolfgang Weihs

I never would have believed that half a lifetime later there would be nothing left of this firmly established world. At the start of the 21st century I was still buying reference works on CD-ROM, which I put on the shelf, still in the slipcase. Knowledge should be something you can touch, it wasn’t fluid – although it was clear even to me that the timespan over which an encyclopaedia becomes out of date was now ridiculously short. And then there was this new knowledge medium called Wikipedia, which renders all books unnecessary and perpetuates the encyclopaedic ideal in the digital age. It only exists online, where it is sustained by a large community and developed on an ongoing basis. If you read an article there, you will find a note detailing when it was last revised, often just a few weeks or months ago.

The Brockhaus on a journey into a new era: in 1985 the reference work was available on CD-ROM for the first time.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/Wolfgang Weihs

I never would have believed that half a lifetime later there would be nothing left of this firmly established world. At the start of the 21st century I was still buying reference works on CD-ROM, which I put on the shelf, still in the slipcase. Knowledge should be something you can touch, it wasn’t fluid – although it was clear even to me that the timespan over which an encyclopaedia becomes out of date was now ridiculously short. And then there was this new knowledge medium called Wikipedia, which renders all books unnecessary and perpetuates the encyclopaedic ideal in the digital age. It only exists online, where it is sustained by a large community and developed on an ongoing basis. If you read an article there, you will find a note detailing when it was last revised, often just a few weeks or months ago.

The age of encyclopaedias on paper endured for a good 200 years. They broadened horizons for millions of people, they set standards and manifested the Western credo “Knowledge is power”. They were the weighty insignia of a society that believes in education through books, and obviously always something of a status symbol too. Sales of the printed edition of the Brockhaus Encyclopaedia ceased on 30th June 2014, while the last printed version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica was published back in 2010.