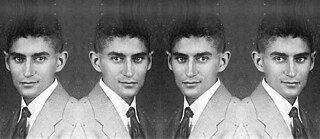

In the Sanatorium Kafka’s Final Days

Franz Kafka was only 40 years old in the spring of 1924 when he was admitted to a private clinic in Kierling, just outside of Vienna. The building has not changed, except for its relationship to world literature.

Morphine and a Silence Cure

He spat blood for the first time in August 1917. He was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis. At the age of 39, he retired from the civil service in Prague and soon learned that the disease had spread to his larynx. Running a continuous fever, on April 11, 1924, he was admitted to the general hospital in Vienna, one of the best in Europe, where he could not bear the sight of death and sought a cure at Doctor Hugo Hoffmann’s private sanatorium in Kierling, a quiet village, today a part of the city of Klosterneuburg. His friend Max Brod, in Prague, and writer Franz Werfel, who lived in Vienna, took care of the arrangements.He was not alone. With him was Dora Diamant, the young Polish woman whom he had met at Graal-Müritz spa in the Baltic Sea, the third woman to whom he was engaged and did not marry, and his good friend Robert Klopstock, who hid doses of morphine in his briefcase to relieve his suffering. Kafka’s room had a sunny balcony overlooking the garden and the forest where he would read and undergo a silence cure. The same garden and forest remain today and the door that separates them still has the original sign that reads: “Sanatorium”. The two-story house at 187 Hauptstraße now houses private dwellings, including the one Kafka occupied. The apartment on exhibit as a memorial is adjacent, where, to everyone’s amazement, countless Koreans visit every year. South Koreans are Kafka fans, fascinated by his work.

The Fire Myth

Without Max Brod there would be no Franz Kafka. While the sheet with the fever curve and the medical record are kept in a glass case (Kafka, who was a tall man—almost 6’1”—and weighed just 99 lbs. when he was admitted), a shelf displays the work he published when he was alive, some 350 pages of stories, among them Metamorphosis, along with some 3400 pages of what Brod salvaged from fire and published posthumously. According to legend, in his will, he ordered the destruction of all his manuscripts, and Brod disobeyed. As it turns out, the one who fabricated the legend was Brod himself, who in addition to being his friend and the executer of his will was also his editor and first biographer, and he created the strategy so that Kafka would not be forgotten and would become known worldwide.Kafka’s desire to burn his work concerned his intimate writings and his unfinished stories and novels—the three novels he wrote: The Missing Person, The Trial and The Castle—. We owe a great deal to Max Brod, and perhaps too much. Novelist Milan Kundera was quick to condemn him noting that by publishing and airing his most personal letters and diaries, Brod betrayed his friend.

Kafka’s Tears

The legend Brod dreamt up cannot explain what happened in that sanatorium during the final days of his life. On the sunny balcony, between air baths and silence cures, Kafka mustered what little strength he had left to correct the proofs of A Hunger Artist (he who was unable to eat), and on that day when he was able to read the proofs of the book he would never see published, he wept.In El mal de Montano (Montano’s Malady), writer Vila-Matas imagined the final scene on June 3, 1924: “When the doctor moved away from the bed for a moment to clean a syringe, Kafka told him: ‘Don’t go.’ The doctor said: ‘No, I’m not going.’ In a deep voice, Kafka replied: ‘I am going.’”

In his last letter, one day before his death, Kafka had written: “… And I am still not very pretty, not at all a sight worth seeing […] So, dear parents, don’t you think that for the moment we should let it go?”

References

- El Danubio (Danube), Claudio Magris. Anagrama, 1988.

- El mal de Montano (Montano’s Malady), Enrique Vila-Matas. Anagrama, 2002.

- Kafka, Reiner Stach. Acantilado, 2016.

- Los testamentos traicionados (Testaments Betrayed), Milan Kundera. Tusquets, 1994.