Autofiction Letters to the parents

Kafka wrote his “Letter to His Father” in 1919, at the age of 36. The letter never reached its addressee but became a famous autobiographical commentary. And just like Kafka, dozens of authors have preoccupied themselves with the entanglements of their identity.

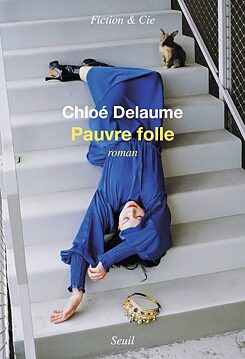

Autobiography, autofiction, fiction ... the boundaries are fluid. Autofiction exists between two poles and tends to blend both genres with each other a little. Facts, persons and emotions are real, but they are enhanced with fantasy; sometimes there is more fantasy, sometimes more reality. The authors play with the ‘I‘ so that it can express itself better. Because when we are confronted with unbearable facts – “Every forty minutes, someone commits suicide in the land of cheese and tranquillisers. And every seven minutes, a woman is sexually harassed or raped,” French writer Chloé Delaume reminds us – it’s better if we can escape. For the author of Pauvre folle (literally: “poor madwoman”), it is “our duty to spin straw into gold if we don’t want to end up in a day-care unit or a private clinic”. Writing means giving things a name so that they exist. In 1983, when her father killed her mother – who wanted to leave him – there was still no word to say femicide and therefore to think about it as such. If you dedicate your life to writing, you also create for yourself a space of resilience. The author finds a memorable image for her experiences: feeling “battered by reality”.Kafka probably felt the same way when he wrote his famous Letter to His Father. The text is like a suitcase in which dozens of small, sharp blades are carefully lined up – words and actions with which the child, young man and adult was relentlessly tormented by his father. The family seems like a sound box of systemic violence, from poisonous pedagogy to male brutality. On a bookshelf, Pauvre folle can be placed not far from Letter to His Father.

The truth: a question of feeling

Annie Ernaux: A Woman's Story |Daniela Dröscher: Lies About My Mother | Monika Helfer: Vati | © Suhrkamp | © Kiepenheuer & Witsch | © Hanser Verlag

Annie Ernaux, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, believes that the ‘I’ is in control of the truth. She sums up in words her personal experience and especially the cultural gap that opens up between herself and her family of origin: “I have availed myself [of my life] like a subject that must be explored in order to grasp and bring to light a kind of emotional truth.”

Who is telling the truth? Who has lied and in what way? Daniela Dröscher asks herself these questions in Lies About My Mother. She explores the blurredness of memories by slipping into the role of her childhood alter ego. Was her mother’s weight really the source of all problems, as her father claimed?

In her 2021 book Vati, Austrian writer Monika Helfer, on the other hand, openly admits to going where fiction makes everything better: “You don’t have to know everything, and if you don’t know everything when telling a story, you can always make it nicer than it originally was. When you know everything, this becomes much harder.” These three authors, too, can be placed around Kafka on the bookshelf.

Writing and reading are political acts

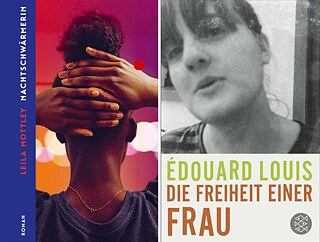

Nightcrawling | Édouard Louis: A Woman’s Battles and Transformations | ©Ecco | © S. Fischer

“Art is the way we imprint ourselves onto the world so there is no way to erase us,” writes African-American author Leila Mottley in her novel Nightcrawling, which was inspired by a true story. She describes the lives of Black girls in Oakland and reveals the reality behind the masks. Just as Kafka reveals the reality about his father: “You […] were perhaps more cheerful before you were disappointed by your children, especially by me, and you were depressed at home (when other people came in, you were quite different).“

And we see the masks when we read these texts. No matter what label is on the shelf, we, the readers of books and the world, can choose who we read. And we can choose to whom we say: I believe you.