These nine fun facts offer you a fresh new glimpse into the life of the great philosopher Immanuel Kant – whether as a colour consultant in all things fashion, as a master of billiards or a culinary connoisseur. With these insights from exhibition curator Agnieszka Lulińska, you’re sure to win any pub quiz.

Cosmos Königsberg

Immanuel Kant spent almost his entire life in the East Prussian capital of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). Born in the city in 1724, he studied and taught there at the venerable Albertus University and died there in 1804. The cosmopolitan port city was the centre of his life and his creative sanctuary. Kant always turned down lucrative teaching offers from other universities. But he kept abreast of global affairs through books, newspapers and the accounts of visitors. His correspondence extended beyond German cities to England, France and Russia. Rather than going out into the world himself, he let the world come to him.

The Gallant Magister

The pleasure-loving private tutor liked to socialise in Königsberg’s refined circles – with aristocratic officers, wealthy merchants and, above all, at the court of the cultivated Count and Countess of Keyserlingk, where he was admired during social gatherings for his intellect and wit. Despite his diminutive stature – Kant was only 1.57 metres tall – he placed great emphasis on sartorial elegance. When choosing colours for his fashionable outfits, he allowed himself to be guided by nature: “[Nature] never creates anything that is not pleasing to the eye [...]. Consider, for instance, how a yellow waistcoat complements a brown frock coat; auricula are prime examples of this.”

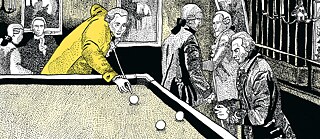

Gambling for a living

Kant was a social climber. His exceptional talents were recognised at an early age, and the son of a humble harness-maker, Johann Georg Kant, enjoyed an excellent education, which at that time was unusual for someone of his social standing. With the financial support of his uncle, he attended Königsberg University from 1740, supplementing his modest budget by working as a private tutor for a small fee. His remarkable skill as a billiards player proved to be far more lucrative. Eventually, opponents declined to compete against him for money, so he switched to

L'Hombre, a popular card game at that time.

Kant and women

Lucky at cards, unlucky in love? Kant spent a great deal of time considering the “fairer sex”, but his personal romantic commitments remain a mystery. Upholding a conservative view of gender roles, he believed men should be further ennobled by their inclinations while women should be further beautified by theirs. Kant viewed marriage as “a need and necessary”, but remained unwed himself – despite purportedly intending to marry in his middle years. He considered the highly educated, art-loving Countess Caroline von Keyserlingk to be the ideal type of woman and an “ornament to her sex”, and was a welcome guest in her home.

The armchair cosmopolitan

People in the 18th century developed an unprecedented passion for travelling. Travel reports from explorers, scholars and merchants became bestsellers. But “armchair travel” also enjoyed enormous popularity – people could go to faraway places without leaving home, but still feed their imaginations. Kant, perhaps the most prominent non-traveller in intellectual history, not only revolutionised thinking, he is now regarded as a pioneer of globalisation. For Kant, Königsberg was an “appropriate place” for “broadening one’s knowledge of man and the world, [...] a place where this can be acquired even without travelling”.

“The soup is served!”

This announcement opened dinner parties at Kant’s house. “Eating alone is unhealthy for a scholar who philosophises [...]. The savouring human being who weakens himself in thought during his solitary meal gradually loses his sprightliness.” At precisely 12.45 p.m., an illustrious circle of friends, local dignitaries and colleagues gathered to partake in culinary and intellectual pleasures. Typically, three courses and a dessert were served. Kant’s favourite dishes included Teltow turnips, Göttingen sausages and cod, seasoned with his much-loved, home-made English mustard. He attached great importance to the quality of the wine.

Fitness for the mind

Immanuel Kant’s meticulously planned routine remains legendary to this day. Each morning at 4.45 a.m., footman Lampe would rouse his master with a military call: “The time is come!” Every aspect of the day was precisely planned: work commitments, meals, social engagements. A fixed part of the ritual was a daily constitutional, which Kant completed along the same route in one to two hours regardless of the season. His walk took him through different neighbourhoods, each with their own social environment. Kant’s friend, the mayor of Königsberg, Theodor Gottfried von Hippel, later referred to it as the “The Philosopher’s Walk”. Kant’s constitutionals were not only beneficial for his ailing health, they also stimulated his mind and provided him with fresh insights and perspectives.

The master and his servant

One of Kant’s most intriguing relationships was with his footman Martin Lampe. The Würzburg-born army veteran worked for Kant for four decades, managing his household affairs and overseeing his daily routine. The unconventional and enigmatic relationship still sparks speculation to this day. As Lampe’s struggles with alcoholism worsened and domestic conflicts increased, Kant was eventually obliged to discharge him in 1802. Kant clearly found it difficult to take this undoubtedly inevitable step. This is evidenced by the significant and paradoxical self-admonition he formulated in his notebook: “The name of Lampe must now be remembered no more.”

Everything Kant would bet on

Kant was not only a philosopher but also a scientist. Half of his oeuvre, over 70 publications and essays, deals with topics we would today classify as the natural sciences. He maintained a keen interest in the latest advancements in physics, geology, geography, anthropology and astronomy. Emblematic of this mindset is the motto of his

General Natural History and Theory of the Heavens from 1755: “Give me matter and I will build a world out of it.” According to Kant’s theory, solar systems like ours emerged from a nebula of matter. Later he even went so far as to say: “If it were possible to settle by any sort of experience whether there are inhabitants of at least some of these planets that we see, I might well bet everything I have on it.”