“J Art Call Center”

Art on Call

At the semi-annual meeting of the Deutscher Bühnenverein (German Theatre Association), around 60 directors of German theatres and orchestras reconsidered the question of where and how they should position themselves in times of political upheaval. The Goethe-Institut Tokyo also took up the topic and discussed it as part of its series “theater anders denken – a new look at theatre”.

By Goethe-Institut Tokyo

The background to the discussion is the closure of part of the Aichi Triennale, the largest Japanese art triennial in Nagoya, in August 2019, where the safety of employees and visitors could no longer be guaranteed due to threats of violence. These threats were directed against the presentation of previously censored works in a special exhibition, for example a work on Japan’s responsibility for war and a sculpture about the “comfort women,” Korean women who were forced to serve as prostitutes for Japanese soldiers – both highly controversial topics in Japan and declared taboo by some.

“ReFreedom Aichi”

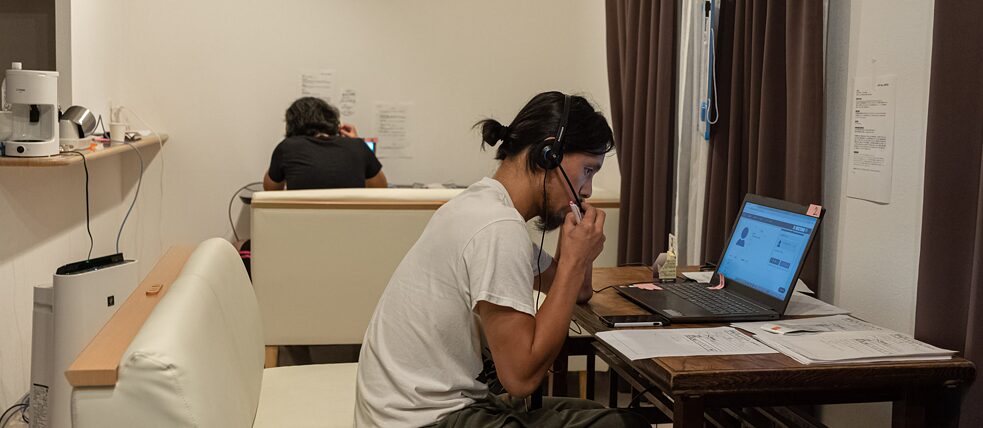

The closing of this special exhibition with the above-mentioned works was seen above all by the participating international artists as “buckling” by the artistic directors in the face of the violent complainants. They thus removed their works. When the Japanese Office for Cultural Affairs subsequently cancelled the promised triennial subsidy, a fierce debate grew on issues of freedom of art and expression in Japan. Among other things, the ReFreedom Aichi initiative was launched with the aim of making the special exhibition accessible again. Over 7 days, about 700 calls were answered. | Photo (detail): © Masahiro Hasunuma

Over 7 days, about 700 calls were answered. | Photo (detail): © Masahiro Hasunuma

Changing power relationships

“We’ve been working with many of the artists involved here for a long time,” says Peter Anders, director of the Goethe-Institut in Tokyo, “Ultimately, the question is how power relations in public discourse change due to violence and hatred in social media and the consequences this has for artists, but also for cultural institutions in general.” On 25 January 2020, Japanese theatre director Akira Takayama, who has also worked in Germany, presented his reaction to the events to a broad audience at the Goethe-Institut Tokyo.7 days, 700 calls

Takayama’s “J Art Call Center” project came into being in response to the flood of complaint calls to the city administration. While the staff there had to adhere to a manual, Takayama used crowdfunding to raise the necessary funds and brought 31 artists, curators, gallery owners and journalists together. They answered over 700 calls within 7 days. In the “J Art Call Center”, mainly “so-called regular people” met the staff environment of the Aichi Triennale. Takayama described how he initially aimed to change the callers’ minds. “But I quickly realized that it wouldn’t work. How can I, convinced that my own opinion is correct, convince someone else that they are wrong? That’s when I simply started listening.” The official logo of the project. | Design: © Washio Tomoyuki

The official logo of the project. | Design: © Washio Tomoyuki