Antanas Sutkus – Photographic Retrospective

Spurned Memory

To celebrate the centenary of the restored state of Lithuania, the Lithuanian National Gallery, in cooperation with the Institut français and the Goethe-Institut, presented the exhibition Kosmos with photographs by Antanas Sutkus.

By Lennart Laberenz

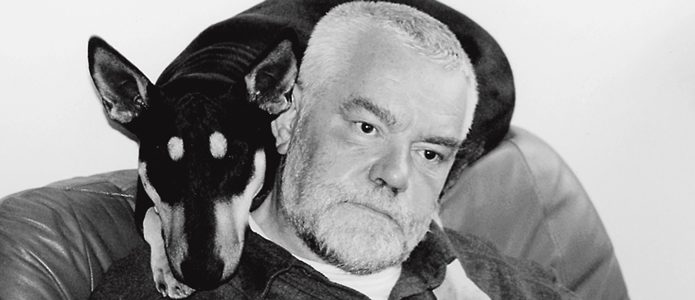

Up the slope behind the railway station are crumbling asphalt, log buildings, wooden houses cowering in hollows; here Vilnius is far from the Baroque beauty of its centre city. In Naujininkai, poverty lurks among the middle class and above it all the sky like a grey veil. Further up are single-family homes; Antanas Sutkus is already sitting on the leather sofa. He has short white hair, boxes lie all about, filing cabinets with handwritten labels, some say Retrospektyva, many say Sartre. Sutkus, soon to be eighty years old, is the most famous photographer of the Lithuanian School. Over one hundred thousand pictures are stored in the basement and here in the conservatory. His wife Rima shrugs, “We live in between them somehow.”

No Title. Vilnius, 1961

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

No Title. Vilnius, 1961

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

Anarchic games, agitated glances

Sutkus co-founded and presided over the Association of Art Photographers in the Soviet Republic of Lithuania in 1969. The idea became a model for the USSR. He had already taken what are his most famous photographs today, de Beauvoir and Sartre in the white sands of the Curonian Spit, clouds, existential emptiness around the bent figures. The blind pioneers, what a metaphor! And always children, anarchic play, agitated glances, skewed horizons, cracked plaster. Uncertainty and surprise in the faces. In 1969, when Sutkus and eight other photographers wanted to open the first exhibition at the Moscow House of Journalists, one critic pulled him aside and told him, “This won’t work. Too gloomy, too depressive.” The critic proposed that they call it the Lithuanian school: that might make it work. Was that resistance? Sutkus turns the word around in his mouth. Stalin had centralized the cultural institutions, the aim of art was not only to express narodnost, nationality, but function as a “demonstration of accomplishments, agreement with party leaders, friendship of peoples, love of the leader.” Sutkus smuggled poetry into his, ambiguity, wrinkled faces, exhausted workers, children’s tears. FARMER. DZUKIJA, 1969

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

FARMER. DZUKIJA, 1969

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

Sutkus learned early: “Resistance was suicide”

His photographs asserted the sometimes poetic, even romantic view of humanistic photography, they tell of the autonomy of art, they rejected journalism, thus propaganda. They found melancholy, barren worlds, and within them absurdities, moments of levity. Resistance? Sutkus talks about his father who shot himself rather than betray his comrades. Antanas was just a year old; his grandparents took over his Christian education. Resistance: In the village they shared their meagre meals with partisans fighting the Soviet Union. A futile undertaking, Sutkus learned early, he smacks the sofa, “Resistance was suicide.” He often encountered problems; the booklet accompanying the wonderful Kosmos exhibition tells about some of them. After the photo of the little pioneer with the shaven head won the Michelangelo D’Oro prize in Italy, it was printed in Sowjetskoye Foto. After outraged comments that it was “dissident photography,” the editor-in-chief was summoned to the Central Committee. It was the Brezhnev era. Sutkus had to join the party so that he could be thrown out. He hid the “Blind Pioneers” photos. Uzupis. High School Children. Vilnius, 1959

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

Uzupis. High School Children. Vilnius, 1959

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

No one is aiming for an effect, no one is posing

His pictures’ strength is their empathy: children draw us into their game, anger, shame, wonder wrestles in their faces. A young woman is weeping for her recently deceased husband. No one is aiming for an effect, no one is posing; Sutkus has an eye for brief pauses, for rest. “The photographer and observer,” he says, “should be on equal footing with the people in the pictures.” The man with the camera is a playmate, a companion. The sofa creaks. With Lithuania’s independence something shifted in the rabid capitalism of the 1990s. On a marketplace, Sutkus observed mothers peddling their last remaining housewares, female buyers who couldn’t even afford to buy their daughters cheap dresses for the feast day. “I couldn’t help them, so I didn’t want to take a picture of them.” Things had become hierarchical. Sutkus saw misery, isolation. “I didn’t want to humiliate them.” FIRST BIKERS. KLAIPĖDA, 1974

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus

FIRST BIKERS. KLAIPĖDA, 1974

| Photo: © Antanas Sutkus