رد فعل متأخر

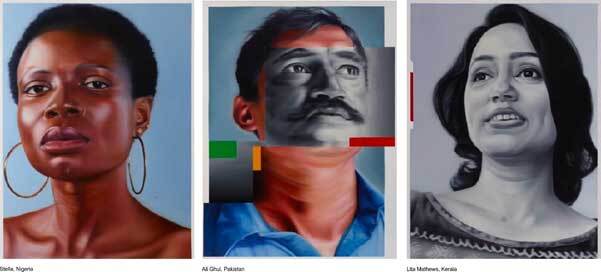

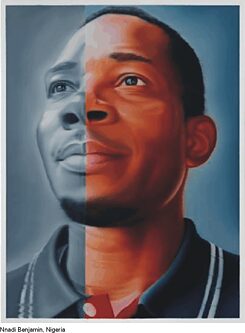

Painted in his famously photographic or hyper-realist style, Riyas Komu’s portraits of migrants from different countries and lines of work in Gulf cities force the viewer to do a doubletake

By Faisal Devji

Painted in his famously photographic or hyper-realist style, Riyas Komu’s portraits of migrants from different countries and lines of work in Gulf cities force the viewer to do a doubletake. What does it mean to conceal the painterliness of these images behind the appearance of their smooth and almost mechanically produced surfaces? Some of his figures are depicted gazing into the distance against a metallic blue background, perhaps the cloudless sky of their desert clime. Others seem to be looking at a camera with the familiar poses and expressions of photographed subjects the world over.

Their physiognomic as well as racial and ethnic differences are reduced if not ironed out by such generic forms of what appears to be photographic representation, in which the carefully posed subjects are themselves full participants. But this is true of Gulf cities more generally, where it is only the minority population of "nationals", as they are known, who dress to be distinguished from the globalized homogeneity represented by the varied individuals who form the demographic majority working for or with them. Foreigners, in other words, not only outnumber natives here, but embody a global norm against which the latter are identified.

This reversal of what is normative and what exceptional goes to the heart of Komu’s work. His hyper-realism functions to de-realize conventional portraiture, which now seems to require visual dissonance of some kind to appear authentic and so truly individual as art. The generic poses of his migrant subjects lend these paintings the paradoxically authentic feel of mass-produced culture, which depends upon its easy reproduction by the democratic choices of individual photographers. But these figures are in the process also normalized as global types linking cities like Dubai to Singapore, London or New York.

We know that such cities share more with each other than they do with their own national hinterlands. And Komu shows us that these links of finance, commodities and consumption as well as population are made possible by migrant labour of various kinds. Beyond the banality of this statement, moreover, his work allows us to see the distinctive migrant histories that go into the making of its ubiquitously global subjects. Komu’s home region of Kerala represents one such history joining India and the Gulf through maritime trade, networks of learning or discipleship and pilgrimage from ancient times.

But the history of migration is neither a single nor continuous one. The spice trade for which Kerala was famous represents one kind of seaborne relationship over centuries. The effort in the middle of the last century by its princely state of Travancore to become an independent Hindu monarchy linked by the sea to the world outside India is another. While labour migration to the Gulf during the oil boom of the 1970s is a third. This last migration had in fact revived the colonial state’s policy of deploying Indian manpower across the Empire, one which had temporarily been halted with the abolition of indenture in 1920.

The discontinuous history linking southern India to southern Arabia overlaps with others involving migration globally. This includes emigration from the subcontinent to Britain in the 1950s and ‘60s and to North America and Australia from the 1970s, paralleling the much larger movement of Indians and other Asian and African populations

to the Gulf. Today it is international as well as civil wars and climate change that are spurring large-scale migration within Asia and Africa as well as smaller movements to Europe and North America.

Komu’s work addresses the reversal that makes an exception of the migrant’s global fate while normalizing citizenship in the nation-state. He shows us how the latter’s normality is achieved by continually repressing all evidence of the contrary through the former’s marginalization. But Gulf states, whose citizens often make up a small minority of their residents, offer a remarkable example of another kind of norm whose alternative cosmopolitanism may well represent a global future with its own advantages and difficulties.

When looking at his own country, Komu focusses on the travails of the poor, low castes, religious minorities and other citizens who do not fit the nation’s image of itself and so tend to invite its marginalizing violence. Instead of repudiating the nation-state or trying to assimilate such populations within it, however, Komu operates another kind of reversal by imagining them as national icons in their own right. And this allows him at the same time to open the iconic figures and symbols of the state both to questioning and even a kind of surreptitious occupation.

Like the Gulf migrants in his hyper-realist portraits, the marginal elements of India’s national life hide in plain sight within its monuments. In Fourth World-I, a set of rubber and metal sculptures from 2017, Komu takes apart the famous lion capital from the reign of the Buddhist Emperor Ashoka that has now become a symbol of the Indian republic. Whereas Ashoka’s four lions are clustered on the capital facing the four directions with their backs to one another, he splits the pillar into four equal parts each with its own lion at the top.

The ambiguity of this gesture is striking: do the lions represent equal but different elements of national life who have finally been given their equal share of freedom, or have they been partitioned by discrimination in the way the country itself was at its founding? Does the undivided lion capital signify unity against outsiders from all directions or a forcibly nationalist unification from within? The split pillar and lion, however, also evokes a celebrated story about one of Vishnu’s incarnations called Narasimha or the man-lion.

Prahlad, the son of a demon king, was a devotee of Vishnu’s, much to his father’s displeasure. Bearing the king’s tortures without complaint, Prahlad prayed for deliverance. His father had received a boon ensuring that he could be killed neither by day nor night, indoors nor outdoors, and neither by man nor beast. One evening, incredulous at Prahlad’s piety, he kicked one of the pillars holding up the palace walls, daring Vishnu to appear. The pillar that was neither inside nor outside promptly split at a time that was neither night nor day to reveal a being who was half man and half lion. Narasimha went on to tear the demon king apart.

By dividing Ashoka’s Buddhist capital, in other words, Komu invoked one of the most famous events in Hindu mythology. And in doing so he doubled the symbolic charge of the sculpture by inserting one story inside another and suggesting that the aggressive lion in the first one might also be the saviour of the second. The Ashokan capital reappears in another work from 2018 called Fear I, where it is hidden in a clump of rushes appropriate for a predator’s lair. Again, we see the play of ambiguity: is the capital’s meaning concealed by the republic or does it in fact represent the latter’s predatory nature?

On the wall behind the capital are displayed the illustrated pages of India’s constitution, one of which is decorated by Ashoka’s lions. Set alongside these well-known images are their reversed duplicates or photographic negatives as if seen on a computer screen. Each of these has stopped downloading part-way through the page, and we are left wondering whether the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the constitution can or cannot be appropriated by all of India’s citizens. Is the document nothing more than an unreachable ideal whose beauty resides in its very unattainability?

In front of the constitution on the wall and the rushes before it with their hidden capital is Fourth Lion II, a life-size acrylic and fibre figure of an animal crouching as if to lap some water from a stream. Released from its stylized depiction on the pages and sculpture behind it, this lion seems to have finally escaped the Ashokan capital to enter reality. Its invocation of Narasimha is clear, but, again, what remains mysterious is the potential and meaning of the violence it represents. Komu’s figurations of national symbols are alive to the ambiguity of their power, whether as mere icons or unchained forces in political life.

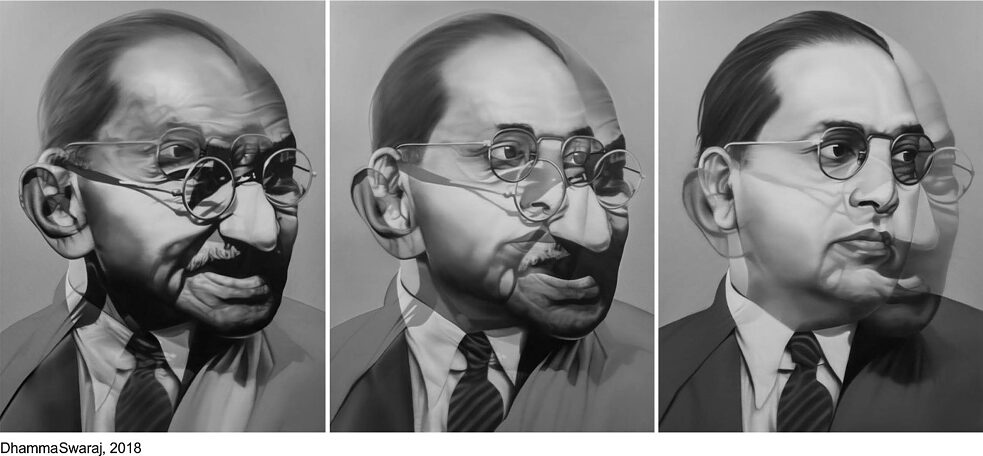

In addition to the material symbols of the republic, Komu also works with its founding fathers. Two in particular seem to fascinate him, Gandhi the apostle of nonviolence and his rival Ambedkar, the low-caste or Dalit leader who was also one of the main authors of the constitution. Fourth World II from 2018 consists of two bronze statues of Ambedkar, each like the Ashokan lions facing away from the other. In his trademark suit with an arm raised to make a point in conversation, the doubled figure of Ambedkar has been installed in a Johannesburg sculpture park.

Placed at a site otherwise known to Indians only for Gandhi’s historical presence there, this work stages their rivalry in representing and making a future for Dalits by acts of migration and occupation. In a country where Gandhi is increasingly seen as a racist, Ambedkar, who had never been there, replaces his compatriot as the symbol of another kind of equality. Bereft of the constitution that is now part of his iconography in India, Ambedkar’s struggle is also universalized beyond Indian history and takes the place of Gandhi’s as its reversal or negative. The focus is on his hands gesturing in persuasion and argument as if in an invitation to conversation and debate.

The contrast with Gandhi’s iconography could not be more striking, with the Mahatma generally depicted in statuary as silent and solitary, even when part of a group as in sculptures representing the famous Salt March of 1930. But Komu is by no means ill-disposed to Gandhi, who appears in a number of his works. Dandi Bridge, a painting of 2019, refers in its name to the Salt March and depicts a bridge under a lowering monsoon sky built into the water without having reached the other side. Like the partially downloaded pages of the constitution, it isn’t clear whether this incomplete bridge needs to be finished or leads nowhere.

Gandhi and Ambedkar come together in another painting, Dhamma-Swaraj of 2018, the first part of whose name refers to the Buddhist path that Ambedkar adopted and propagated, and the second to the self-rule that the Mahatma advocated. The three panels of this work show a kind of struggle between or fatal embrace of the two men’s portraits, with one layered over or inserted into the other to make a ghost out of each. Whereas the first panel is dominated by Gandhi’s face, with Ambedkar’s lying below its surface like a spectre, by the third their roles have been reversed and Gandhi turned into a ghost haunting Ambedkar’s portrait. Yet it remains unclear which position is the more powerful. Is the hidden Gandhi, like the Ashokan capital hidden in the rushes, a truth concealed or a force whose threat remains unseen?

We have seen that Komu’s work is characterized by reversal and doubling, both ways of multiplying meaning to foreground the undecidable and so in some ways purely aesthetic element in social as much as political life. The mobility of his migrant figures betrays a history of both freedom and compulsion. Their portraits speak as much of these subjects as for or even against them like evidence that can be used by the authorities. While the silent iconography of Gandhi speaks volumes, Ambedkar’s ceaselessly speaking and gesticulating statuary may never be heard. Is the Mahatma who has vanished into his rival’s portrait more powerful than the mere husk the latter has become in the process?

A set of metal sculptures from 2019 called Song Unsung dramatize these issues with startling clarity. They comprise faces made up of metal bands, giving them the appearance of bound or imprisoned figures. Before the possibly bared or barred mouth of each hangs a microphone. The artist tells us that this work represents a way of coming to terms with the genealogy of torture. Undecidable is whether it is the denial of speech that these faces signify or the forced confessions of torture. The uncomfortable but not dissonant coming together of free and forced speech, as of Gandhi and Ambedkar in an earlier work, is also true of the migrant’s freedom and compulsion as we have seen.

Is confession preferable or silence? Does the republic represent freedom or fear? Perhaps the choice is not ours to make. Riyas Komu’s work rehearses these impossible alternatives, or rather their ceaseless struggle which he suggests is what gives shape to our public and private lives. No one person, policy or principle can be made to voice any singular meaning or import. Their incompletion may be a tragedy as much as a saving grace, which is what his work on India’s constitution and its republican symbols seems to tell us. But a world of such multiple and intertwined meanings allows us room to make some of our own while escaping others in the process. It is a world not of clear-cut differences and their pluralism but of endlessly wrestled intimacies.

Faisal Devji

Professor of Indian History

University of Oxford