Interview

The ICA welcomes CTM Festival to London

Since its inception in 1999, CTM Festival has encapsulated Berlin’s avante-garde music and arts scene. Usually set out over ten days, CTM invites a plethora of artists to play with the possibilities and limitations of music and sound. Through concerts, exhibitions, workshops and club nights, the festival acts as a nucleus for learning, reflection and exchange with a strong focus on narratives of social change. Its 25th iteration will take place between the 24th of January and the 4th of February 2024.

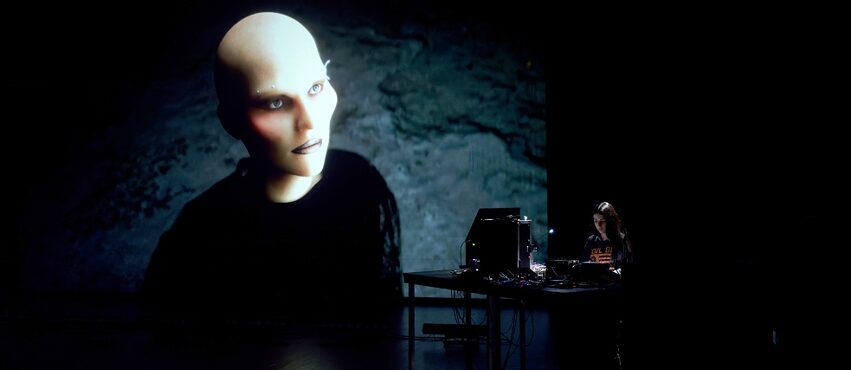

From the 20th until the 22nd of October 2023, the galvanising energy of CTM will be transported to London for the first time. The ICA’s theatre will become home to the late-night programmes of DJs, live sets and UK premieres, and its cinema will screen live audiovisual projects, which respond to experiences of war in Ukraine. In true CTM style, the Saturday night will conclude with an afterparty at South London’s Venue MOT club. The Goethe-Institut London and the Goethe-Institut in Exile are both supporters.

For this interview, we spoke to co-founder and artistic director Jan Rohlf and senior curator James Grabsch about musical curation of the CTM x ICA programme, lessons of cross-cultural exchange and creating a place of refuge within the music and arts scene.

By Lucy Rowan

We are really excited to finally welcome CTM to London this year. How did this collaboration with the ICA come about and how will this two-day programme differ from the usual Berlin rendition?

James: The ICA has always been pivotal to my relationship with London - whenever I visited, I always had such an incredible time there. Our colleague Remco was actually talking to Bengi Ünsal when she was still working at the South Bank Centre, and they discussed doing something together. Then Bengi moved to the ICA, and once she made the switch, she was like: “Hey, let’s do it now!” So yeah, it's been really exciting and cool to finally work collaboratively, and with such a special organisation.

Jan: CTM had also been conversing with the Goethe-Institut London for many years about bringing CTM activities to the city, but somehow it never really worked out. And then there was COVID and so forth, so the idea came to a halt. So for this to all finally be happening is amazing.

CTM festival, in its complete version, usually brings together a range of formats like exhibitions, mini workshops, concerts and club nights. In the two-day-long London version, we cannot be that comprehensive. Instead, we are focussing on the actual music performances. In our programming, we often also try to go beyond the classic concert or club formats to do things that are also slightly politically motivated or discursive. And so, with the split between the cinema room and the theatre room, we had some room to play with and to bring in some of those aspects.

It’s a privilege to work with the ICA and be a part of that legacy because it's not just an iconic venue for visual arts, but the history of the organisation is also important when it comes to underground music. Many artists and bands that have been influential in their own listening trajectory had crucial moments at the ICA.

How do you typically go about selecting artists for festivals? How does the selection of London artists, for example, reflect your core mission?

James: I would say this differs from person to person - there are four curators and we all have a slightly different approach because we come from different backgrounds. I would say that I probably had the most influence on the London programming and as a musician, I travel a lot and regularly see other artists on the road. For this version, we wanted to bring the CTM experience to London. So we are working with artists who we have already worked with a lot of times before, but the London audience might not be so familiar with. They are basically artists that we have already kind of “tested out” and worked well with before. And there are also some of our favourite artists that we almost think of as extended family. They’re all going to present new works that we haven't seen yet. So this is just as exciting for us.

Jan: Since it's such a condensed version of what we usually do, that within a night alone there are certain aspects covered. And I guess the people who join us there will go through a little journey of different ways of experiencing sound or listening to music. In this sense, we wanted to explore aspects of perception. For example, Stephanie will create a rather conceptual, immersive multi-speaker performance that becomes more of a vibrational experience compared to a conventional music experience like a concert. Whereas the group Prison Religion have an entirely different approach - they use formats of noise and formative presence to address actual political issues that are of concern to them. We also want to showcase the sounds that we have gotten excited about in recent years within a club/rave setting - this rather industrial-punk-infused, fast-paced noise and highly intense rave clap sound.

James: We're aiming to cover many different grounds and formats, but what unites them is that it's all cutting edge - the artists sit on the fringes of experimental music and sound. Overall, we wanted to cover different aspects of the types of music you would find at CTM. But they all have a certain intensity in common.

Jan: Over the years, we have worked with many artists at CTM that actually have had a residency at Somerset House Studios or still have one. So we came to the realisation that it's quite a lively and productive hub for people working with sound and music, but especially for some kind of cross-disciplinary collaboration that is coming out of that environment. And then when I had the chance to visit London to meet everyone at Somerset House Studios, we had a brilliant day of exchange and realised we had a lot of overlap of ideas on how to support and promote artistic practises as organisations.

So the idea was born - we could work together on a yearly residency to bring an artist based in Germany to London to benefit from that environment and to connect with other artists in the city. We also want to support them with their work towards a new project, which after an initial period in London, could be developed further and then presented at the next CTM festival.

I think it's important to keep up this connection between the UK and Germany, especially after Brexit. There's this paradox that the UK has always been so strong in the musical landscape: the media, the agencies, all the professional infrastructure, and the number of artists that basically get sent into the world to present their music. But the actual eye-to-eye level collaboration between organisations to actually do something together has been much less developed and when we looked at it, rather thin. But this is a different way to deal with things, and it's important to establish that level of organisational collaboration rather than just bring artists from the UK everywhere else.

It's kind of ironic that these collaborative visions are coming to life within a post-Brexit context. Despite difficult travel, visa and migration restrictions, how can we continue to build a cultural exchange bridge between the UK and Germany, particularly when it comes to music and supporting artists? What role can the Goethe-Institut play in that?

James: It's an interesting question because as mentioned earlier, we have been bringing artists from the UK to CTM for many years. If I look at the collaboration with the ICA, I feel that the part that is taking the longest amount of time is where you have to deal with visas. It's also the trickiest thing. So it’s rather difficult to answer that question with a positive answer or with the perfect solution - it’s a really difficult political question and I’m not sure I can actually answer it.

But, when we think about the role the Goethe-Institut can play, I can only really answer this on a wider scale perspective. I've been working a lot with the Goethe-Institut Cairo as part of my personal life as a musician and it was really interesting to see how much the Goethe-Instituts - there are three in Cairo - support local culture and the exportation of local music. So I would answer this question by saying that the Goethe-Instituts of the world can definitely help in these times of austerity measures and complicated situations like Brexit, which make the lives of artists so much more difficult.

Jan: Well, an obvious thing is in an environment where everyone has to deal with the challenges and scarcities, collaboration is ever more crucial. That is on a personal level between artists, but also on the level of organisations and initiatives. Nothing should be taken for granted and we must keep this up between the UK and Germany. It's really something that has to be actively fostered and it usually needs someone to kind of mediate or initiate it. Or at least it needs moments of connection where people are kind of brought together and these ideas can spark.

No one would expect that an organisation that has existed for 25 years in Berlin and an organisation that has existed for 75 years in London (ICA) would naturally come together and do things. But it's not like that. So I think in that regard, the Goethe-Institut has a very positive role and they see it as their mission to stimulate people to make such connections. I think that should be kept up and intensified. The harder the divisions in this world, the more we need to build these bridges actively. I think that is the only answer.

Jan: For many, many years we very consciously have been trying to build relations with artists, organisations and initiatives in many places in the world, including those that have become difficult environments for arts and culture, in particular Iran and Ukraine. So I think there is a great overlap with what the project wants to do and I guess that’s the reason why we connected. Of course, the mission of Goethe in Exile goes far beyond that. What they do in terms of giving a safe space and a platform for diaspora cultural protagonists, artists, producers to keep networking, to keep exchanging, to have a place where they can meet, and be together is something they do to a much further extent than we can.

This is why we came together to support artists in producing new work and performance works that address the situations in Ukraine, Syria, Iran and Peru. The countries are all so different culturally and politically, but we are finding the common ground between experiences to create a space for artists to try to express themselves together in a collaborative audiovisual performance. Shared feelings and experiences of violence, displacement and the threat of erasure of their culture. In the theatre room at the ICA x CTM festival, there will be two instances where such dialogue will be part of the performances (Alex Guevara and Katharina Gryvul, and Diana Azzuz and Nazanin Noori).

They have produced a series of film vignettes, where artists from Ukraine revisit crucial moments and certain experiences that they had to endure since the full-scale invasion of their country. In the snippets, they revisit the actual places in Ukraine where these experiences happened. It's a kind of POV-style documentary combined with a new soundscape composed by these artists.

So it's the creation of very personal pieces of storytelling that give people a view into the current reality in Ukraine. What is interesting about it is that it is far removed from the images that we are fed by the media, which focus on the front lines, the actual soldiers fighting or the dropping of bombs on cities. Of course, destruction is addressed in these films but we see that through many different points of view, in a much more personal way. I think it's truly touching and a very important project that gives you access to the crisis on an emotional level, a more human way of connecting and showing solidarity.

How has Berlin been impacted by international war and censorship in the past few years? What changes have you seen to the music and art scenes as a result?

Jan: I think throughout the last decade, Berlin, like other places in the world, has become a place where a lot of people arrive from countries where they are struggling or are under threat politically, where people are oppressed and cannot express their views freely. So Berlin has become a place for people where they feel they can live a different life that is not under threat from a political regime or where they will encounter a lot of conflict for having diverse perspectives. When new people arrive in Berlin, so does a general awareness of what is happening elsewhere and people have to become more aware of their privileges.

So I think there has been a massive shift in how we perceive what's happening in the world. We can’t ignore these things anymore because they are far away. We are faced with these issues daily. I find it means you need to really learn and upgrade a lot. All of us need to be very sensitive.

20 years ago, Berlin seemed to be swimming in its own bubble quite comfortably. One could just focus on some aesthetic interest that was detached from troubles happening in the world. I don’t think that’s possible anymore. But in some ways, that is a good thing - we all have to grow and face up to questions about how we can help repair these situations.

James: Well, I mean, I don't know how it was in the UK, but the war in the Ukraine really impacted us directly and a lot of the people working in the music scene were working to help migrants because we had such a gigantic influx of people suddenly. Over the years, I think there were lots of different factors that impacted our lives in Berlin, but the war most definitely. It caused this crazy inflation that we can all really feel - from the price of produce to club entrance fees. It has made it incredibly difficult to realise the goal that we have for accessibility for the festival. It’s generally just getting more and more difficult to make things happen. We had a recent change of government in Berlin, which is also kind of a direct result of the war. This has led to gigantic cuts to public funding, which affects everyone working in our sector.

On the other hand, we have this huge privilege and opportunity to exchange and collaborate with all of these people who we have now welcomed into our lives. Without meeting them, we wouldn’t have had the chance to showcase their artwork.

Jan: Every situation is different, of course. So it can be hard to find the common denominator. However, one crucial element from the outset is that nobody should go into an exchange that is across continents and cultures with an attitude that the ways that you are used to doing things is and should be the standard. You have to throw those ideas away from the start. European culture for centuries has been going about this in a very oppressing way and there's a lot of repair to be done, which means you're also facing a lot of scepticism when you enter those conversations, and rightfully so. From the start, it's important that you listen and also give space to that scepticism and reservations others have towards you, and then you can start building some trust. Without mutual trust, it doesn’t work. A humble attitude and being attentive are essential.

James, as an artist (Born in Flamez), you have had the chance to travel a lot with your music. What important teachings have you learnt from those experiences about the binding elements of artistry across cultures?

James: I think what’s been most interesting for me, through being an artist, I have been able to explore different music scenes in places that seem really remote to me, where the dominant culture is completely different to what I know. But wherever I go and whoever I meet, we have the same questions. These universal questions are about how to create safe spaces, how to build community and how to build an ecosystem. But then, of course, the answers differ completely and possibilities differ depending on what the dominant culture is. For example, a discussion about safe spaces varies in a place where it's very hard for you to exist as a female-identifying person or as a queer person. I find that element of finding common ground the most beautiful thing, but whilst it unites, it also differentiates us at the same time.

James: I think trends are very difficult to forecast because you're always kind of rooted in a specific kind of scene. So when I forecast a trend for Berlin nightlife, this would come out of my perspective as a queer white person. So I can't give you an unbiased answer. I think from my perspective, what is changing in Berlin is that we see a lot more community-based events and a lot more smaller events catering to different types of crowds. This is something that's really great to see. There's also more awareness of different things like accessibility. For example, there is a sliding scale for entrance fees at the door so you can talk to the people who are putting on the event about your financial situation and maybe get in with a lower entrance price. I think that's a very current development in Berlin that I welcome not just here but in other cities.

Jan: I think as a response to the very stressed economic situation, we will see what James was describing - a much smaller-scale grassroots kind of DIY nightlife that very consciously wants to go against this grandscalling of club nights. Maybe not paying high fees to artists and keeping things more localised, more community-driven. But how this will work in practice I am not so sure, we will need to see what happens.