February 2019

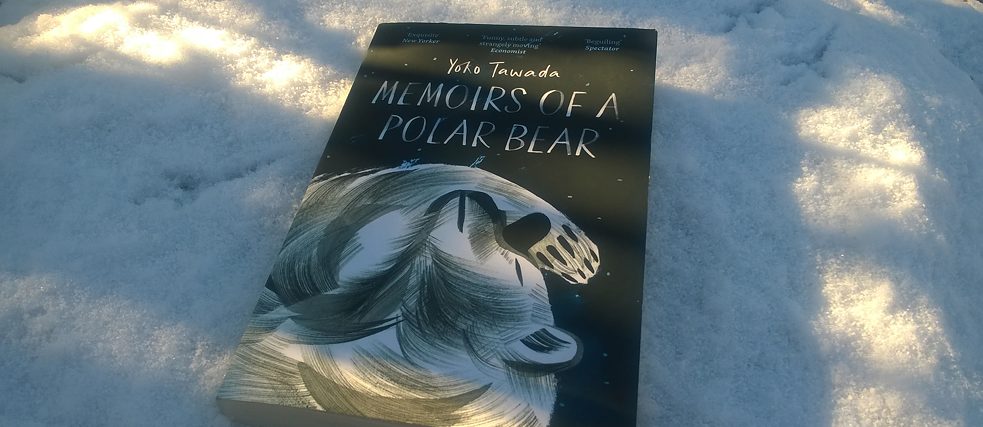

Memoirs of a Polar Bear: Studies in Snow

On re-reading Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear (tr. Susan Bernofsky) in advance of this month’s blog post, I realised that in choosing the novel, I’d shot myself in the foot: sombre yet humorous, disrupting moments of social realism with dream-like sequences, this book isn’t quite like anything else I’ve ever read.

Memoirs of a Polar Bear, which won the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation upon its publication in English, almost works as three separate novellas, each telling the tale of a generation from the same bear family: an unlikely memoirist forced to flee the Soviet Union; her daughter Tosca, a skilled circus performer in East Germany; and Knut, Berlin zoo’s polar bear cub who really did take the international media by storm in the noughties. How to offer a point of comparison to this strange yet remarkable book?

One possible might be Nights at the Circus: raucous, sensuous and unsettling, Nights at the Circus is arguably Angela Carter’s most popular novel – with good reason. Following the exploits and adventures of a fin-de-siècle circus as it makes its way from London to Saint Petersburg and across the tundra of Siberia, the tale revolves around Sophie Fevvers, an aerialist whose apparent wings are the subject of much speculation. The novel also touches on the bonds between the circus’s discerning animals and their people, and Carter’s magic realism disquiets both reader and characters with clocks which repeatedly strike midnight and toy trains which transform into their life-size counterparts.

Readers uncomfortable with the darker aspects of Carter’s writing will be relieved to know that Tawada has none of Carter’s sadism – but Memoirs of a Polar Bear does reverberate with echoes of Carter’s off-kilter storytelling. The book is laced with moments of disjunction and shifting perspectives which give it the solidity of quicksand; while Tosca never learns to speak human language, her mother lives a remarkably ‘human’ life – despite an inconveniently large appetite and a predilection for the cold. Rather than upsetting the novel though, these contradictions lend it a dream-like quality, which becomes pervasive in the second section, when Tosca and her trainer Barbara communicate principally through dreams.

This surreal atmosphere goes hand in hand with beautiful observations and descriptions (my particular favourite was a suave activist’s “rosy voice with lots of thorns”). These frequently gain humour when the bears’ unusual perspectives defamiliarise the everyday:

“I can’t actually get sick. Someone told me once that illness was a traditional form of theatre practiced by office workers, who were allowed to put on these performances only on Mondays when they didn’t want to come to work.”

Interweaving compassion with humour, Memoirs of a Polar Bear offers an eerie yet somehow familiar journey through the past fifty years, asking as it does so what it really means to be human.