July 2021

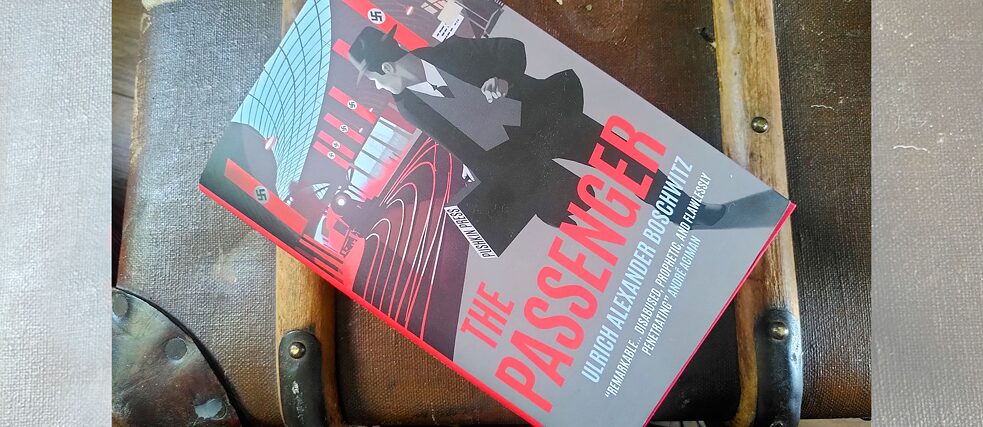

Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz: The Passenger

If John Buchan’s The 39 Steps had you riveted, we recommend Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s The Passenger.

I normally avoid books set during the Nazi period for this blog. This isn’t due to any “don’t mention the war” etiquette, but instead because books exploring Germany’s darker days tend to do just fine on the British book market, and I’d rather shine a spotlight on the remarkable diversity (in both subject and genre) of writing translated from German. It became clear pretty quickly though that Ulrich Boschwitz’s The Passenger (in a slick translation by Philip Boehm) was a novel worth making an exception for.

The book’s history is fascinating in itself: the 23-year-old Ulrich Boschwitz, a Jewish exile living in Paris, wrote the tale of Otto Silbermann in the feverish weeks following Kristallnacht. Early versions of the novel were published in the UK and France, and Boschwitz himself fled to England, where he was interred as an enemy alien. He died in 1943, aged only 27. Boschwitz’s wish that The Passenger be published in a liberated Germany wouldn’t be fulfilled until 2018.

Boschwitz’s own incessant travelling as an exile (to Sweden, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, England and ultimately – as a prisoner – to Australia) is reflected in the aimless journeys which form the core of The Passenger. Otto Silbermann is a successful Jewish businessman, who for the first five years of the Nazi regime had managed to fly more or less under the radar, protected by wealth, connections and an ‘Aryan’ appearance. When SA thugs arrive at his home on 9 November 1938, he is forced to flee out the back door. With anti-Jewish violence erupting across Germany, Silbermann can no longer close his eyes to what is happening in his country. Thus begins an odyssey of increasingly desperate train journeys crisscrossing Germany.

It’s a gripping read, with the constant motion and the atmosphere of suspicion reminiscent of John Buchan’s classic thriller The 39 Steps. Admittedly, Otto Silbermann is no Richard Hannay, but this is one of the novel’s strengths. Boschwitz doesn’t try to make Silbermann a hero – he’s a little pompous, easily irritated, and occasionally cruel. The scene in which Silberman snaps at a more obviously Jewish friend is heart-wrenching:

- A few minutes later he clapped Silbermann on the shoulder. “We’ll stick together,” he said cheerfully

- “You’re putting me in jeopardy,” Silbermann exclaimed, both agitated and annoyed.

Lustiger stared at him. His face lost the look of contentment it had taken on while they were eating, his eyes widened, and his mouth opened as if he wanted to stay something, but he was silent.

Yet as Silbermann’s desperation and anxiety grow, the reader can’t help but root for him. Novels in which the main character isn’t overly sympathetic are always a tightrope act, and Boschwitz manages this challenge with agility and ease.

Written before the death camps had been established, the novel has been described as prophetic. Reading it now, as with nationalism on the rise at home and abroad, is an unsettling experience in the most necessary of ways.

About the author

Annie Rutherford is an incorrigible bookworm and Jill of all (word-based) trades. She is the Assistant Festival Director at StAnza (Scotland’s international poetry festival), a German-English literary translator, and runs Lighthouse Bookshop’s Women in Translation book group, among other things. She has been known to read while cycling (she does not recommend it), and can spot a misplaced apostrophe at a distance of fifty yards.Borrow the original German title digitally via the eLibrary.

Reserve your copy of the translated book in our library in London.

Find out more about the blog.