More than a festival

Out film festival

By Kevin Mwachiro

Screening of KIKI at the Goethe- Institut Nairobi's Auditorium © Goethe-Institut

I will never forget the first edition of the OUT Film Festival for various things. But, of course, the anxiety came with the preparations, willingness to support the event from well-wishers, or its simplicity, even then but primarily for its bravery and how it tried to establish a Kenyan identity for itself.

Screening of KIKI at the Goethe- Institut Nairobi's Auditorium © Goethe-Institut

I will never forget the first edition of the OUT Film Festival for various things. But, of course, the anxiety came with the preparations, willingness to support the event from well-wishers, or its simplicity, even then but primarily for its bravery and how it tried to establish a Kenyan identity for itself.

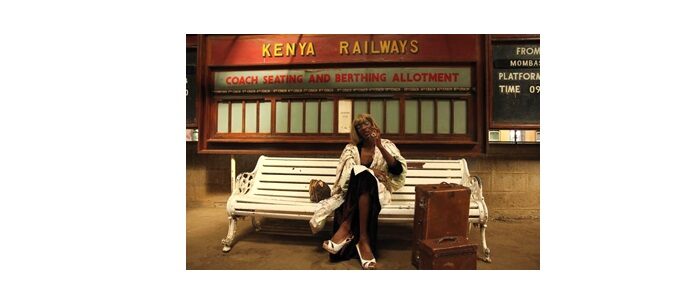

As co-founder, I don’t want to take credit for that because the universe was busy orchestrating ways to ensure the festival would make a name for itself. The initial poster had an image from Fluorescent Sin, a movie about a Kenyan cross-dresser having a nervous breakdown at Nairobi Railway Station. It was directed by a Kenyan, Amirah Tajdin, and OUT was its first public screening in Kenya. How cool is that? During the same edition, two other Kenyan titles and several films from the continent reflected the diversity of queerness.

Poster of the first ever OUT festival containing an image from 'Fluorescent Sin' © Goethe-Institut

We were received warmly but cautiously by the public. The queer community was unsure whether it was safe to even attend the festival, but there was a healthy group of allies who just showed up. We expected trouble because of the content that we were going to screen—not violence but some form of disruption. A few months before, I'd witnessed anti-abortion activists disrupt a conversation on the perils of unsafe abortions just next door at the Alliance Française. So, we were not throwing caution to the wind.

Poster of the first ever OUT festival containing an image from 'Fluorescent Sin' © Goethe-Institut

We were received warmly but cautiously by the public. The queer community was unsure whether it was safe to even attend the festival, but there was a healthy group of allies who just showed up. We expected trouble because of the content that we were going to screen—not violence but some form of disruption. A few months before, I'd witnessed anti-abortion activists disrupt a conversation on the perils of unsafe abortions just next door at the Alliance Française. So, we were not throwing caution to the wind.

Fortunately, nothing happened but film. As a result, the festival has grown in confidence, content and character over the years. And Kenya's queer community champion the festival and claim it as their own. Laurent Bouchat, the director of the film Woubi Cheri, notes, “To watch a film surrounded by a public that share the very same life experiences and feelings is a very unique emotion you can’t get anywhere else.” This feeling is empowering and the number of times I have seen the auditorium erupt in emotion, snapping, clapping, cheering or jeering at a scene or statement, is testament to the power of a collective.

“Every culture’s history is essential. Everyone deserves to have their lives elevated through the beauty of truthful representation.” These words spoken by self-described nice guy, public speaker and author, Rohit Bargava, underscore the importance of festivals like OUT. It saddens me deeply that Kenyan movies that have been acclaimed globally are still to make their debut at the festival. Stories of Our Lives, Rafiki and I Am Samuel are powerful and beautiful films in their own right. Yet, a system that is unwilling to watch and learn about its own people has banned these movies from Kenyan audiences.

Since the end of the Moi era, the country's art sector has flourished and keeps going from strength to strength. We see more locally produced films, and the industry is churning out talented actors and filmmakers. But queer content still isn’t making its way to our local screens or audiences. People say that Kenya isn’t ready for ‘controversial’ topics. But the LGBTQ community, like any other community, deserves to have their story told in a way that they want it to be told. What better time than the present? The three aforementioned movies and the interest that they have generated is proof enough that Kenya is ready.

Panel discussion at Goethe Insitut's Auditorium © Goethe-Institut

“We need to keep an eye on the other human experiences to give ourselves the fullness and the breadth of our own humanity. Our humanity is served back to us through the eyes of those who have diminished us. And they serve back to us a view of ourselves that is incomplete. If we don’t look to the bigger picture, our view will narrow to that which is constantly fed to us.” As the world mourns the recent death of the acclaimed actor Sidney Poitier, his words amplify the importance of creating content that correctly portrays honest realities. Therefore, OUT has constantly endeavoured to have a healthy amount of Kenyan and African content, created by fellow Kenyans or fellow Africans. OUT has made a commitment to ensure that LGBTQ stories are not diminished.

Panel discussion at Goethe Insitut's Auditorium © Goethe-Institut

“We need to keep an eye on the other human experiences to give ourselves the fullness and the breadth of our own humanity. Our humanity is served back to us through the eyes of those who have diminished us. And they serve back to us a view of ourselves that is incomplete. If we don’t look to the bigger picture, our view will narrow to that which is constantly fed to us.” As the world mourns the recent death of the acclaimed actor Sidney Poitier, his words amplify the importance of creating content that correctly portrays honest realities. Therefore, OUT has constantly endeavoured to have a healthy amount of Kenyan and African content, created by fellow Kenyans or fellow Africans. OUT has made a commitment to ensure that LGBTQ stories are not diminished.

I grew up when there wasn’t much Kenyan or African content making its way onto the big screen. Let me take you back in time. I remember when the Ghanian movie, Love Brewed in an African Pot, came to the cinemas in the early 1980s. There were queues outside the 20th Century cinema to watch the film. Sadly, I was underage and therefore couldn’t watch the movie, but I remember the excitement that it solicited. Then, finally, an African movie with African actors was being screened! Fast forward a few years later to Saikati, by Anne Mungai, which was released in 1992. I am sure there were other Kenyan films, but they were not often screened at the Kenya, Nairobi or 20th Century cinemas, which were the more popular movie theatres. These movies stood out for me because they celebrated our African identity and they screened to full houses. We were able to see ourselves and our stories outside of the heavy diet of Western film that we were being fed on at the time. Representation matters.

I was overjoyed when we screened Dakan, by Mohammed Camara. This is the first West African film to tackle the subject of homosexuality directed by an African. Who would have thought that in 1997, there was a movie on African gay love that had been produced? Dakan is an iconic film and is part of our queer African history. The queer reality on the continent is not a single story. OUT has also been keen to portray other realities outside of the continent and has been able to look back to the early years of the activist LGBTQ movement. Our queer history matters.

“We need to open up a space to talk more about sex, and then artists like me want to open that up, even more, to talk about queerness,” said the late Kawira Mwirichia, the celebrated queer artist whose work was showcased during one of the editions of the festival.

a panel discussion of the Out Film Festival held at the Goethe Institut © Goethe-Institut

It was slowly becoming apparent that OUT was not just a kawaida [normal] film festival. It has evolved into a space for self-expression and low-key advocacy. The panel conversations became a highlight of the festival and began drawing in numbers. The discussions allowed our reality, as the Kenyan LGBTQ community, to be ventilated. It was a place for learning if one's mind was open enough. I will never forget the panel discussion on lesbian love and sex. I blushed and laughed in equal portions. There were panels that surprised all of us. Some were uncomfortably candid as the community bared itself naked. Again, this is not a kawaida festival.

a panel discussion of the Out Film Festival held at the Goethe Institut © Goethe-Institut

It was slowly becoming apparent that OUT was not just a kawaida [normal] film festival. It has evolved into a space for self-expression and low-key advocacy. The panel conversations became a highlight of the festival and began drawing in numbers. The discussions allowed our reality, as the Kenyan LGBTQ community, to be ventilated. It was a place for learning if one's mind was open enough. I will never forget the panel discussion on lesbian love and sex. I blushed and laughed in equal portions. There were panels that surprised all of us. Some were uncomfortably candid as the community bared itself naked. Again, this is not a kawaida festival.

This is a festival about life. Queer life. I remember when we screened God Loves Uganda, we were lucky enough to have Ugandan activists passing through Nairobi and they stumbled across the festival. We asked them questions about the now relegated Anti-Homosexuality Act and their experience of living as queer individuals in a country that is unapologetic in its discrimination towards the LGBTQ community. On the other hand, the Ugandans couldn't believe that we were able to freely host such an event without any state interference. A few years back, the festival coincided with World Aids Day, and during the day the auditorium temporarily turned into a VCT—Voluntary Counselling and Testing centre. It was fascinating seeing people just walk off the streets to either get condoms, femidoms or wanting to know about their HIV status. In commemoration of the day, that evening we lit candles outside the auditorium. The idea was good on paper, the execution could have been better, but our intention was pure.

private film screening of the festival © Goethe-Institut

And then there was COVID. Like the rest of the world, we had to rethink dealing with the new normal. OUT went virtual, and this opened the festival to an even wider Kenyan audience with community screenings held in Mombasa, Eldoret, Malindi and, of course, Nairobi. OUT innovated and broadened its tentacles. It stopped being a Nairobi festival, and I hope future iterations will be a cocktail of the various ‘normals’ that are now part of our lives.

private film screening of the festival © Goethe-Institut

And then there was COVID. Like the rest of the world, we had to rethink dealing with the new normal. OUT went virtual, and this opened the festival to an even wider Kenyan audience with community screenings held in Mombasa, Eldoret, Malindi and, of course, Nairobi. OUT innovated and broadened its tentacles. It stopped being a Nairobi festival, and I hope future iterations will be a cocktail of the various ‘normals’ that are now part of our lives.

Out Film Festival, at it's 10th anniversary, was the winner at 2021's Ubunifu Awards © Kevin Mwachiro

It has not been plain sailing, but every time the festival kicks off, there's a massive sigh of relief and excitement, but fingers are kept crossed that the festival runs smoothly and uninterrupted. The festival has made me appreciate the power of innovation, and like water, it will find a way to its final destination. The destination, in my opinion, is a depiction of a love that is very normal and a celebration of our reality and how the power of storytelling through film can build bridges, educate, entertain, empower and, more than anything, offer a window to oneself.

Out Film Festival, at it's 10th anniversary, was the winner at 2021's Ubunifu Awards © Kevin Mwachiro

It has not been plain sailing, but every time the festival kicks off, there's a massive sigh of relief and excitement, but fingers are kept crossed that the festival runs smoothly and uninterrupted. The festival has made me appreciate the power of innovation, and like water, it will find a way to its final destination. The destination, in my opinion, is a depiction of a love that is very normal and a celebration of our reality and how the power of storytelling through film can build bridges, educate, entertain, empower and, more than anything, offer a window to oneself.