Kafka's Metaphors

Please introduce yourself briefly.

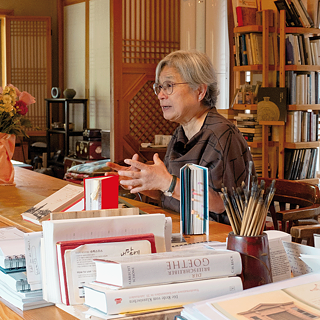

Hello, I'm Youngae Chon, the founder and operator of Yeobaek Seowon, a place in Yeoju that serves as a publishing and library facility as well as a place of learning, similar to where scholars met during the Joseon Dynasty. Recently, I initiated my major project called “Goethe Village”. Throughout my life, I have dedicated myself to the study of German literature.Kafka was born in the Czech Republic. Please explain why his works belong to German literature.

Kafka was born in 1883 and died in 1924. Many people in Prague City Hall spoke German because, at that time, Prague was part of the Habsburg kingdom, where German was commonly spoken. Approximately one-tenth of the population in Prague spoke German. Kafka, who was Jewish, had a father who was successful and enabled him to immerse himself in the German-speaking world of the upper classes, allowing him to read, write, and comment in German. Therefore, his work is undoubtedly part of German literature and the essence of modern German literature. It's no surprise that the Goethe-Institut is interested in Kafka; it would be inappropriate for them not to be.You translated Kafka's novels in the 1980s, and now you translated them again in 2023. What has changed?

The first translation was done a long time ago, back in 1979, when I translated the first set of short stories. I've been thinking about how outdated they may seem today, considering their age. I considered revising and republishing the entire thing, so I spent last year going through each sentence. However, I didn't make many changes because I had worked so hard on it initially. I did attempt to rewrite smaller parts, such as the first line of “The Metamorphosis”: “Gregor Samsa woke up one morning to find he had turned into a beetle.” That sentence sounds natural, doesn't it? Ultimately, I decided to stick very closely to every single word Kafka wrote, so: “When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin.” Kafka wrote each piece with great care, and I felt that his writing should be encountered in its original form rather than being summarized or explained. So that was the result of 30 years of reflection.Kafka's works are full of metaphors. What difficulties did you encounter when translating?

No, it wasn't difficult at all. I was so grateful to have the chance to read such great texts that I didn't find it challenging to translate. When working on the famous opening sentence, my main goal was to preserve its tone. Kafka's writing allows for various interpretations, which is why he remains one of the most widely studied writers in the world.The word “vermin” is interesting because we usually associate it with “I am like a vermin”, but Kafka skips that step and simply discusses “vermin”. He begins with the beetle, describing it so precisely and accurately that you can picture it crawling around. However, when you reconsider, it's not the story of a beetle, but of a human being living in an industrial society. There's so much packed into this metaphor.

I'm pleased that many people recognize the true literary quality behind this metaphor. At the same time, I'm troubled by the idea that we all experience the problems of industrial society and suffer from them.

Kafka's novel “The Metamorphosis” is particularly popular in Korea. Why do you think that is?

I had just mentioned it briefly and got a bit ahead of the answer to this question...There is no explanation as to why I am a bug. I go to work every day as a beetle and live my life as a beetle, but why I became a beetle is not clear. However, to understand the beetle's transformation, we must understand the suffering of the man who became a beetle. This becomes clear in the course of Kafka's story.

In the course of the story, it becomes evident that Gregor was forced to become a beetle. It is not just the hectic pace of industrial society and the feeling of being marginalized. The pressure continues in the family: “What if my father gets sick? What happens if I'm ill? But if I never become a bug – what happens if I feel as worthless as one?” Until he turned into a beetle, the whole family lived dependent on Gregor Samsa. But after his transformation, everyone begins to fend for themselves, doing their work and even setting up a pension. And when he crawls out as a beetle, they throw apples at him to drive him away. He is hit by the apple and dies. Well, in these scenes, reality and unreality are so closely intertwined. Then Gregor suddenly hears the sound of the violin of the sister he wanted to give a musical education and says to himself: “Am I an animal that I am so moved by music?” This feeling is so well drawn.

It's a poignant story. I transform into a bug and die, but my family, rather than mourn, goes on a picnic. However, when I see what my students write, I find a glimmer of hope. It begs the question: how can one have hope in the face of such circumstances? If Kafka had explicitly written a story with the message “Have hope!”, the likely reaction would have been, “No, it's hard to have hope.” However, because Kafka vividly portrays Gregor's feelings of despair and frustration, it offers a different perspective. It evokes a sense that in a more humane society, this situation could have been resolved. I believe that these thoughts are what captivate people about Kafka's novel. Mathematical problems have solutions, but the problems in life often do not. They are complex and do not have easy answers. However, if we confront the situation directly and delve into its depths, I believe we will find the strength to cope. Therefore, literature, not just Kafka's works, provides us with the fortitude we need. At times, we can only live our lives and experience our emotions. When I read a book like 'The Metamorphosis,' I think about my father and the challenges he faced. It also makes me consider people with disabilities and imagine what it would be like to live with that disability. Literature like this prompts us to think deeply about the lives and experiences of others, which is why it's important to read.

Please give us some examples of what you find so fascinating or unusual about Kafka's short stories.

If I had to choose just one story, I think it would be “Before the Law”. This story is just over a page long, but it paints a clear picture of life. It's about a person who tries to walk through a door but is stopped. Eventually, they die, only to hear a voice saying that the door was meant only for them all their life. This powerful story made me reflect a lot on my own life. Kafka's other short stories are also worth reading.I also like “Community”. It's a house from which five friends come out at random and line up. But when a sixth friend joins and stops, it disrupts the group. It's challenging to explain why it doesn't work, and it's interesting to read about exclusion and taking sides in this short play. Another characteristic of Kafka's writing style is his frequent use of animals or animal metaphors. Monkeys, cats, and even mice make appearances. Similar to Aesop's fables, the animals in Kafka's stories often impart meaningful lessons. In his works, this is often how he deals with despair or frustration, and animals are a way of expressing these feelings. It's not about drawing animals beautifully or teaching someone a lesson, but the stories about despair are strangely encouraging.

What would you say to future readers who have not yet read Kafka?

Kafka's works are not difficult to read; they're enjoyable. I highly recommend reading his short stories as they are quite inspiring and thought-provoking. One of Kafka's famous quotes from his letter, “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us” sums up the power of literature quite well. Kafka truly valued the importance of books, and you could benefit greatly from reading his works. I believe you will find his short stories very enjoyable. Thank you!Have you heard this question before? It was very popular last year... Recently, students called their parents and asked them on KakaoTalk: "What would you do if I turned into a cockroach or vermin?", and the answers were very different. I found out that the question came from Kafka's literature...

That's quite amusing! I find it great that Kafka's work is so widely accepted.

However, I believe that the question of what I would do if my mother turned into vermin would be even better. Don't you think? I wish we could change the direction of the discussion towards that.

Instead of asking, “What will you do for me?” it should be more like, “I've changed. What will I do for you if you turn into cockroaches?” We should turn it around like that.

This question needs to be asked in this manner once again...