“We need to get used to manipulation as a society”

- Dynamics of mis- and disinformation in East Asia and Europe

- How does generative AI change information environments and media literacy interventions?

- Talking politics: State regulations and ideologies

- Picture gallery: A look at four countries: How to deal with misinformation and hate speech?

- Harnessing global perspectives for collective solutions

- Conference program and speakers

Misinformation and conspiracy theories have always been part of the fabric of society. However, the advent of the internet and the rise of social media have fundamentally changed the dissemination of news and its consumption. Recent developments in AI technology and easy-to-use tools for media production have further accelerated the spread of information. In many societies, rumors that spread across the world, false information, and the incitement of hate speech have deepened societal rifts and increased polarization.

To better understand these dynamics and discuss how interventions have been implemented the Goethe-Institut and the German Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb) jointly organized “Facts & Contexts Matter: Media Literacy in East Asia and Europe”. Experts from Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Germany discussed their regions and the methods they employ to combat mis- and disinformation, and online hate speech.

Dynamics of mis- and disinformation in East Asia and Europe

Research interest, both from academia and journalism, in the “threat” of mis- and disinformation has grown steadily across the world over the past years. The keynote speakers Masato Kajimoto, Hong Kong University, and Jeanette Hofmann, Freie Universität Berlin, agreed that the actual threat of mis- and disinformation is at times overblown, and lacks depth and context as well as empirical grounding. “We often assume that misinformation is a problem of the platforms, although a lot of false and misleading information comes from top-down – from the political elite”, said Hofmann and Kajimoto added: “Misinformation is rather a symptom of polarization, inequality, hate, mistrust, and other issues – not the cause.”The impact of mis- and disinformation on voting behaviors or hate crimes is often hard to measure scientifically, however, both experts talked about the influence of group identity in the sharing of misleading information: “You share information to signal which political group you belong to, not necessarily because you believe it”, said Hofmann. “If everyone was aware of tribal behavior, the situation might be better. We should include education on group behaviors and not focus on short, technology-centered education”, said Kajimoto, who believes in media literacy education as long as it goes beyond fact-checking. “We should focus more on identifying and creating credible quality content.” With his student-led newsroom, fact-checking project Annie Lab, and the Asian Network of News and Information Educators (ANNIE) this is exactly what his team and network have been doing since 2019.

While Hofmann stressed that high-quality media was one of the best and most important ways to battle mis- and disinformation, Kajimoto flagged the lack of high-quality information in languages other than English. This can be problematic, especially in times of a global health pandemic. Where high quality information is lacking, rumors have space to grow.

How does generative AI change information environments and media literacy interventions?

The AI models we have in place reflect the regulations and ethics of the places where the systems are built. “At the moment, our AI models are mostly in line with what US companies think we should value”, said Antonio Krueger, CEO and scientific director of the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence, “and Chinese models are in line with how Chinese regulators think they should work.”Krueger reflected more generally on the power of generative AI and ways to include, for example, watermarks in photos and videos to distinguish human from artificial content. The other two panelists spoke of local applications using generative AI. In South Korea, the popular chatbot Iruda, which had been strongly criticized after disseminating hate speech, was tamed by introducing a generative AI model. “The first version of Iruda was trained by 100 million chats retrieved from the “Science of Love Service” (a platform on relationship advice). Her hate speech came from chats humans exchanged”, recounted Sungook Hong, Seoul National University. He researched how Iruda was transformed and explained how the tech start-up Scatter Lab, which programmed Iruda, established ethical principles in co-creation with the ICT Policy Institute and Iruda’s users.

Use artificial networks to stimulate human neuro networks – this was the message of Isabel Hou’s input, who is the Secretary General of the non-profit organization Taiwan AI Academy, which aims to educate industrial stakeholders on AI technology trends. In her talk, she introduced the fact-checking bot Cofacts, which runs on open-source technology and whose database consists of knowledge crowdsourced by active users. Hou stressed that generative AI alone is no silver bullet: “Empower readers to enhance their digital literacy so that they can make their own decisions.” And Krueger added: “We need to get used to manipulation as a society – and learn new tools.” Tools, which are informed by a diverse range of stakeholders.

Talking politics: State regulations and ideologies

On August 25, 2023, the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) officially came into power. Tech giants like Google, Meta, and Amazon are now being held to stricter standards of accountability for content posted on their platforms and need to include feedback options for their customers to be able to report problematic content. Mauritius Dorn from the think tank Institute of Strategic Dialogue explained how the DSA works and recounted some of the discussions that led to the Act aiming to foster safer online environments. He talked about problematic areas: “We need to be aware of what elements we as European Union are focusing on in our cyber diplomacy.” Jeanette Hofmann, Freie Universität Berlin, who moderated the session, added: “The problem is that it is up to the nation-states to define illegal content and thus what platforms need to take down.” This is especially crucial in states where courts are not independent. The DSA could end up as a powerful tool for EU countries that restrict the right to freedom of speech.

Daisuke Furuta, editor-in-chief of Japan FactCheck Center claims that this may be one of the reasons the Japanese government is against platform regulations. “In Japan, the study group on platform services of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications recommended that the private sector should combat misinformation, rather than it being regulated by law.” Organizations with a “neutral governance structure” should be strengthened. “Of course, private fact-checking organizations cannot deal with big tech platforms alone”, noted Furuta and mentioned the need for some kind of regulation. “However, this is not a priority of our current government.” Overall, it seems that Japan is less affected by misinformation and disinformation – like for example its neighbor Taiwan, where Furuta’s fact-check organization has close ties with like-minded organizations: “Most fact-checking tools are from Western countries, but we lack for example Chinese language tools. Taiwan is at the forefront of developing these.” According to him, more knowledge of “non-Western” platforms like the Chinese microblogging service Weibo or the Japanese instant messaging app LINE is needed to combat misinformation or harmful speech.

Picture gallery: A look at four countries: How to deal with misinformation and hate speech?

-

Sookeung Jung, Policy Chair of the Citizen Coalition for Democratic Media (CCDM), talked about the activities of South Korea’s oldest media watch organization, which was founded in 1984 to accompany South Korea’s transition from a dictatorship to a democracy.

-

Disinformation and Media Literacy Policy in Japan. While Jun Sakamoto (picture above), Hosei University, talked about different media literacy policy interventions, for example in schools and libraries, Emi Nagasawa (picture below) from the think tank SmartNews Media Research Institute (SMRI) introduced a media literacy game, among other activities.

-

Fighting disinformation and hate speech in Germany: Simone Rafael from the NGO Amadeu Antonio Stiftung presented activities of the organization, which range from digital street work, journalistic activities to advocacy and training of multipliers tackling hate speech online but also offline.

-

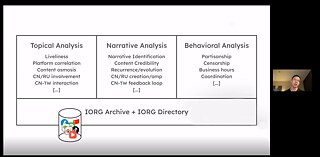

Building an information credibility network in Taiwan: Healthy environments depend on strong networks. Chihhao Yu, Co-director of the NGO Taiwan Information Research Center (IORG) sketched Taiwan’s dense network of different non-governmental organizations which work in research, journalism, fact-checking, education etc. to build a network of trust in society.

Harnessing global perspectives for collective solutions

The last panel specifically looked at the connection between misinformation and hate speech and started off with a question about the definition of hate speech. What actually is hate speech? “In Germany, the constitutional prominence of human dignity shapes our approach to hate speech”, said Mauritius Dorn, ISD. “In South Korea the definition focuses on discrimination. Hate speech means that people are excluded from mainstream society”, added Sookeung Jung, CCDM. Isabel Hou, Taiwan AI Academy, senses a strong focus on disinformation that could be linked to hate speech, however, the courts in Taiwan define what hate speech is. Masato Kajimoto, Hong Kong University, raised the problem of politized courts in some countries in Asia, and Dorn added that platforms have plenty of scope to design their products and policies, which is why more transparency of content moderation and recommender systems is urgently needed. The DSA tries to contribute to this endeavor.The panelists agreed that a holistic approach is necessary to tackle hate speech. “Legal regulation is not enough. There needs to be behavioral regulation, that directly prohibits hate speech from being expressed, for example in classrooms. Also, digital environments need to be modified so that it becomes harder to engage in hate speech”, said Jung. Kajimoto outlined different ways that classrooms could address this problem. Some address only what’s being said. Others say: “Let’s learn about the history, let’s learn about the psychology of hate, let’s open wounds.” The panelists noted that media literacy education should address people of all age groups. Approaches for tackling hate speech require good coordination and the engagement of the whole society. For Dorn it’s also about “innovating democracies” via new tools and spaces in the public interest: “We are in a state of multiple crises, so we need spaces where people can get fact-based information about the impact of issues on their lives and ask their questions without hate and agitation.”

All in all, the conference showed that Asian and European countries have more in common when it comes to dealing with misinformation than perhaps initially assumed.