Traces of Germany in Lebanon

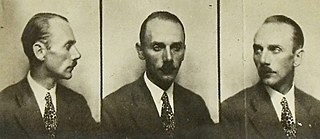

The Imposter of the Middle East – Walter Schmerl

This is the tale of a brazen con artist, who used a series of false identities to cause havoc throughout the entire Middle East early in the 1930s. In the guise of an aristocrat, this impostor exclusively targeted fellow Germans, claiming a financial emergency or pretending to be an enterprising businessman looking for partners for lucrative business ventures.

German expatriates fell for this scam time and time again – especially those who weren’t exactly reputable merchants themselves. Several consular officers proved similarly gullible, allowing this con artist to continue with his schemes despite glaring inconsistencies in his stories. And when they finally decided to intervene, he had already left their consular district. In the end, it was a routine procedure by the Consulate in Beirut that finally blew the lid off this case. But first things first.

A certain ‘Fritz Ströbele’, born in Hechingen on 29 July 1906, first came into contact with the German authorities in Beirut on 7 July 1930 due to a fairly trivial matter. He claimed to have been passing through on his way from Baghdad back to Germany, when his passport and wallet were stolen in the souks of Beirut. His passport had been issued by the authorities in Stuttgart, or so he said, and now he needed a replacement.

The man was in a hurry to leave the country, so the Consulate issued a new passport that same day, and as a routine measure, they informed both the passport office in Stuttgart and the Consulates General of the region, including the ones in Jerusalem, Smyrna, Baghdad and Alexandria, as well as the Legation in Tehran, the Embassy in Cairo and the Consular Section in Istanbul. Up to this point, things seemed perfectly normal.

But on the evening of the following day, the German authorities in Baghdad wired back that something was fishy about the man’s story. The real Fritz Ströbele was still in Baghdad, however an ‘adventurer’ had left the city on 3 July using Ströbele’s passport. This ‘adventurer’ also had a second passport, issued in Breslau (modern-day Wrocław) to a man going by the name of ‘Ludwig Buchholz’. The Embassy in Baghdad asked their colleagues in Beirut to seize Ströbele’s passport and return it to Baghdad, and to determine the identity of this ‘adventurer’. Apparently, he had left behind debts to the tune of 7,000 Reichsmarks.

On 12 July, the Consulate in Beirut received another note from Baghdad detailing how this debt had come about. It stated that the “farmer and author Ludwig Buchholz” had turned up in Baghdad in early February of that year and had immediately taken out a loan of 6,000 Reichsmarks to lease farmland from the King’s steward. He had refused to disclose any information about his past to the Consulate and had only briefly shown the Consulate secretary his papers on one occasion. Recently, he had started the rumour that his real name wasn’t Buchholz, but that he was in fact an aristocratic German cavalry officer with a warrant out on his head for his involvement in the so-called Feme murders in Germany and in the assassination of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau.

Two days later, the consulate in Alexandria reported back that the ‘adventurer’ was actually a German named ‘Walter Schmerl’, also known as ‘Otto Zarnekow’, who was born in Erfurt and was wanted in connection with a number of scams. A pertinent detail included in his physical description was that the little finger of his right hand was missing a phalanx. It was to be assumed that he intended to try ‘his luck’ with the passport issued in Beirut. Furthermore, German, Austrian and Yugoslavian police had issued warrants for Schmerl/Zarnekow’s arrest for a variety of crimes. Only later did it become clear that the official in Alexandria had hit the nail on the head.

According to the German Consul in Baghdad Wilhelm Litten (1880-1932) – Litten is remembered today for his eyewitness accounts of the death marches in 1916 during the Armenian genocide – the wanted man had involved a German merchant named Hans Krumpeter in his dealings. He had introduced himself to Krumpeter as ‘Count Walter von Kalkreuth from Siegersdorf-Vieselbach,’ and lured him in with the prospect of ‘a few thousand pounds’. He had then left the country on 3 July with the stated intention of withdrawing the funds in Zurich.

But Consul Litten added that ‘Buchholz’s’ business partner Krumpeter was hardly an innocent victim himself. While in Tehran he had already amassed considerable debt and had been ‘negligent’ in keeping accounts relating to his management duties at a Soviet company called Rustransit. He had been granted a second chance in Baghdad, especially due to his language skills and local knowledge. And so Krumpeter had soon been tasked with representing a number of German companies, including the E. Merck chemical factory in Darmstadt. After a while, however, Krumpeter had reverted to his true nature. His correspondence had remained unanswered, and he had got involved with people the Consulate had explicitly warned him against dealing with. Furthermore, he had employed workers such as the previously mentioned Fritz Ströbele on his estate under slave-like conditions, not only refusing to pay him his wages, but also talking him out of the money provided to him by the Consulate for his return home. In the end, he had even confiscated Ströbele’s passport and had later passed it on to the elusive ‘Buchholz’.

When ‘Buchholz’ arrived, Krumpeter had immediately involved him in his dealings. Together, they had succeeded in convincing the King’s steward to lease them additional land. King Faisal I (1883-1993, reigned 1921-1933) himself was reported to have taken a ‘keen interest’ in the farming project ‘Landheim zur Schlanken Linie’ (‘Country Manor at the Slim Line’), and had not only visited the estate but had also granted the fraudulent farmer ‘Buchholz’ several audiences.

If Litten’s account is to be believed, the Krumpeter/‘Buchholz’ estate was a popular destination for the German expatriate community in Baghdad. Due to the high profits predicted by the two business partners, many Germans had been impressed and had invested money in the farming project. Furthermore, the German community had generously provided the assiduous ‘Buchholz’ with all sorts of supplies.

The Consul had first suspected something was amiss when ‘Buchholz’ needlessly flooded the German war cemetery he had been tasked with overseeing – and for which he had already received an advance – causing considerable damage. The Consulate had taken care of the restoration costs. ‘Buchholz’ was unable to make a statement on what transpired because he had fallen ill. He had moved from the country estate into the Krumpeters’ townhouse, where he sought medical attention.

More strange events followed soon after: while he was at a Polish doctor’s house for examinations, ‘Buchholz’ had accused the Iraqi domestic staff of stealing 20 Reichsmarks. In a fury, ‘Buchholz’ had demanded his money back from the doctor, who gave it to him. On the same day, it had also been reported that another 250 Reichsmarks of the doctor’s money had been stolen, which was also blamed on the local domestic staff.

‘Buchholz’ became more and more brazen: soon after, he had approached Litten and demanded a loan of 300 Reichsmarks because locusts were eating away at his fields and the workers were on strike because they hadn’t received their wages. He claimed Krumpeter had fallen behind on his payments. Despite grave doubts, Consul Litten had granted him the loan, to be repaid on 1 July, because he didn’t want people saying he had caused “this company to fall victim to a locust infestation because of hardheartedness”.

The con man had also tried his luck with Litten’s wife: he had brought her a loaf of bread and claimed to have opened a country bakery. He had proposed that she place several orders and – of course – pay for them in advance. And he had also asked her to tell the English women about his bakery. After the wife had refused to pay or to spread the word, the bakery was never mentioned again.

‘Buchholz’ was unmasked in early June, when the Consul learned of Ströbele’s employment at the estate and as a reaction had first summoned Ströbele, and then ‘Buchholz’ to the Consulate. At this point, ‘Buchholz’ admitted that he had been using an alias and told his cock-and-bull ‘Kalkreuth Feme murder’ story. He claimed he had to wait for amnesty to be granted, after which he could sort things out and clear up any questions.

Although Litten even pointed out that this sounded a whole lot like something a con man would say, he didn’t act right away. The Consul was worried it might damage his good rapport with King Faisal if it came out that ‘Kalkreuth’ had committed several counts of forgery or fraud according to Iraqi law. And Krumpeter would have been ruined too.

After ‘Kalkreuth’ reported to the Consulate that he couldn’t export his sweetcorn harvest to Germany due to German sweetcorn regulations, and therefore couldn’t pay his debts, Ströbele, who had lent his money to Krumpeter and ‘Kalkreuth’, was forced to admit on 2 July that he couldn’t pay back the loan he had received from the Consulate to pay for his journey home. He still hadn’t been paid by Krumpeter.

That was the final straw for the Consul. Litten made serious accusations against Ströbele, calling him a “repatriation swindler for a gang of crooks”. He said he would no longer see Ströbele or ‘Kalkreuth’ in person; they would have to meet with his deputy, Dr Brücklmeier from then on.

‘Kalkreuth’, who had been waiting in the antechamber and had heard the Consul’s frank words, went to see Brücklmeier and complained about the Consul’s choice of words. But now ‘Kalkreuth’ had been forced into a corner and was looking to find a way to leave the country as quickly as possible. He therefore asked for a deferral of 20 days to settle all of his outstanding payments. His request was granted.

This was a very generous concession by the Consulate, but more than just a little naive in light of all the preceding events, and ‘Kalkreuth’ had no qualms exploiting it – he left Baghdad overnight. Krumpeter had prepared his getaway and provided him with Ströbele’s travel documents. The plan was for the two of them to meet in Zurich in two weeks' time to work out their financial affairs.

Krumpeter did not yet realise that he had just become yet another of the con artist’s victims. Once it became known that the ‘Count’ had skipped town, Krumpeter refused any cooperation with the Consulate at first, referring to a vow of silence he had pledged to the ‘Count of Kalkreuth’. He didn’t want to jeopardise the contract he had concluded with ‘Kalkreuth’, which he thought would relieve him of all his debts. But when Litten showed him photos of the impostor in Alexandria, Krumpeter filed a criminal complaint against ‘Buchholz/Kalkreuth’ on 18 July 1930.

By then, it had become known that the absconder had perpetrated another scam during his brief sojourn in Beirut, before departing for Damascus. With the help of a Hungarian forger by the name of Zoltan Silbermann, while staying at the Hotel Imperial, he had drafted a letter of recommendation for the ‘Count von Kalreuth’ with the forged signature of Consul Litten, which he had used to solicit yet more victims. Two German lorry drivers, whom ‘Kalkreuth’ had asked for a short-term loan in Damascus, had confiscated this document along with a copy of the contract with Krumpeter and had brought them to Baghdad.

Other aliases ‘Kalkreuth’ had used included ‘Walter Ulmerl’, ‘Boris Romanoff’ and ‘Count von Ehrenreich’. Now he was in Aleppo, posing as ‘Hermann Schanz’. He had stolen the documents from a charitable German technician who had even let him stay the night at his residence.

In response to this, the consular secretary wrote the following on 1 August:

“I’m truly surprised that he hasn’t been apprehended yet, but I’m hopeful that this will finally succeed soon, so that this modern-day Captain of Köpenick can be brought to justice.”

But matters became even more convoluted: further inquiries made in Haifa into the papers that ‘Kalkreuth’ had left behind in Baghdad showed that the impostor was also responsible for at least one marriage scam. Apparently the charming and charismatic man had promised to marry a Miriam Rosenberg, while a nurse named Hilde Hochwald had fallen in love with him in Haifa and was still suffering from the break-up.

The things the imposter 'Buchholz' abandoned in Baghdad showed him to have connections to Erfurt and also led to the discovery of the real Buchholz’s identity, who didn’t realise he had lost his passport in Haifa until several months later. Word also got out that the version of the name used by the con man didn’t even exist, the true spelling was with a ‘ck’ (i.e. Kalckreuth).

And his true identity now finally came to light: it was Walter Schmerl, born in Erfurt on 15 April 1896. He had deserted his post in 1915 and first turned up in Bad Herzburg in 1916, using the alias Karl von Törne. He had been charged with fraud in Zagreb in 1927. One year later, he had attempted to scam support money in Elbersfeld (Wuppertal).

The next notes in the fugitive’s file were from February 1931 in Istanbul, where Schmerl had once again called attention to himself by stealing the papers of a certain Erich Mahle. He had also briefly been put in prison by the Turkish authorities, who accused him of arson. From there, he had escaped to Ethiopia.

Even though the files make no direct mention of a successful arrest, the final piece of news in this complicated case from 6 June 1932 does however indicate that Schmerl’s good fortune was about to come to an end. He had been afflicted with a severe case of malaria during a steamboat journey from Djibouti to Genoa and had arrived at his destination on 6 May. The German Consulate General there had taken ‘all necessary steps’.

This closed the book on a criminal case that had kept the German diplomatic missions in the Middle East on their toes for the past two years.

Source:

Hochstapler Schmerl-Buchholz [‘The Imposter Schmerl-Buchholz’], in: Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes [PAAA] (Political Archive of the Foreign Ministry), Beirut Consulate, Package 86