Joseph Beuys

Fat, felt and legends

In May 2021, Germany is celebrating a special art centenary on what would have been legendary artist Joseph Beuys’ 100th birthday. We look at what made the provocative lateral thinker tick.

By Romy König

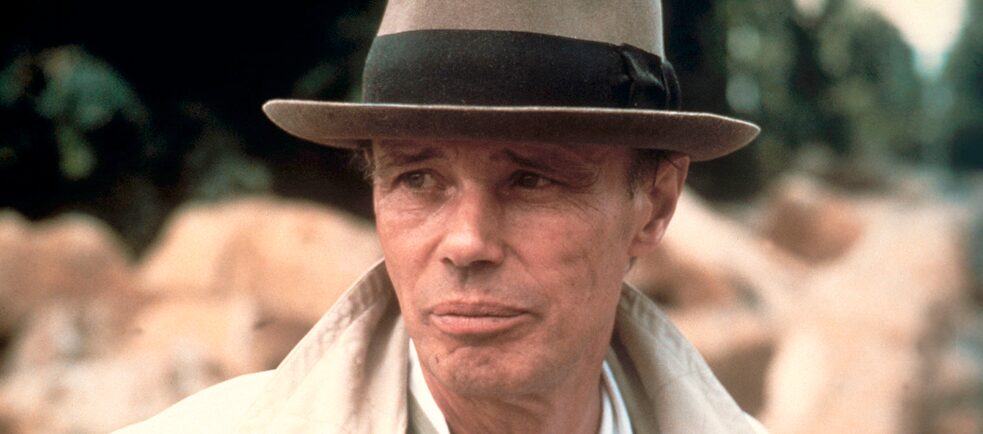

Anyone who saw him once would not soon forget his look: Joseph Beuys’ appearance alone – fishing vest, white shirt, jeans and obligatory felt hat – is burned into the collective memory of the art world. His iconic pieces, his artistic actions, and the legends – which he often encouraged – surrounding his person are even more so.

Born in Krefeld in the Rhineland in 1921, the artist generated a furore in the middle of the last century primarily by transgressing traditional genre boundaries. Beuys was a draftsman and sculptor, conceptual artist and political thinker, art philosopher and spiritualist – and both his oeuvre and the quotations and slogans he handed down reflect his universalist thinking. “Every person is an artist,” Beuys once said, “whether they are a garbage collector, a nurse, a doctor, an engineer, or a farmer.” Beuys, who studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy where he would later work as a professor, was convinced that wherever a person “develops his or her abilities,” he or she is an artist – and added provocatively: “I’m not saying that this is more likely to result in art in painting than in mechanical engineering.”

Radical idea: art and life as one

This attitude is part of a concept that Beuys called the “social sculpture” or the “expanded concept of art”. This concept is built on the idea that thought, art and social and political discourse are to be understood as one unified entity where art and life are intertwined and inform each other – another radically new idea in the art world of the 1960s and 1970s. Beuys wanted to disenchant – and enliven – objects of art and exhibition venues. About works of art, he said ideas froze in inside them and would “eventually be left behind”, adding that people were the ones through whom “ideas moved on”. Beuys wanted to see the museum not as a treasure trove, as Ina Conzen of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart explains, “but as a living place of continual discussion.” The Baden-Wuerttemberg capital will host one of the many exhibitions highlighting Beuys’s work in the summer of 2021 to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth. Conzen curated the show, which is devoted to Beuys’s relationship with the museum as an institution. “He felt that the museum should be more of a place for social debate.”

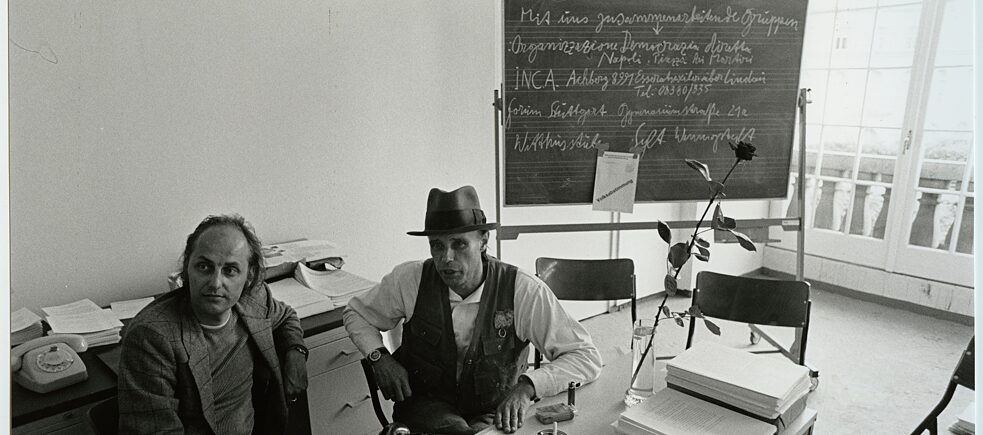

Art is meant to be political: In 1971, Joseph Beuys and other artists founded the political “Organisation for Direct Democracy” with an office in Düsseldorf – and one year later, at documenta 5, unceremoniously opened a branch office in his exhibition pavilion as a piece entitled: “Office for Direct Democracy through Referendum”.

| Photo (detail): © documenta Archiv © Estate of Joseph Beuys / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014, Photo: Brigitte Hellgoth

This was also evident in Kassel in 1972: When Beuys took part in the renowned exhibition series for contemporary art, the documenta 5, he did not bring sculptures or exhibit drawings. Instead he moved his office, the Büro für direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (Office for Direct Democracy through Referendum) into the exhibition space assigned to him. There he sat and waited for visitors to engage in discussion about how to design direct democracy.

Art is meant to be political: In 1971, Joseph Beuys and other artists founded the political “Organisation for Direct Democracy” with an office in Düsseldorf – and one year later, at documenta 5, unceremoniously opened a branch office in his exhibition pavilion as a piece entitled: “Office for Direct Democracy through Referendum”.

| Photo (detail): © documenta Archiv © Estate of Joseph Beuys / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014, Photo: Brigitte Hellgoth

This was also evident in Kassel in 1972: When Beuys took part in the renowned exhibition series for contemporary art, the documenta 5, he did not bring sculptures or exhibit drawings. Instead he moved his office, the Büro für direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (Office for Direct Democracy through Referendum) into the exhibition space assigned to him. There he sat and waited for visitors to engage in discussion about how to design direct democracy.

A man, the materials and the myth

And yet it would be wrong to reduce Joseph Beuys, who died in Düsseldorf in 1986, to his work as a performance artist. He also introduced a “new material language,” Ina Conzen explains. His 1963 Stuhl mit Fett (Fat Chair), about which he later explained that the fat “takes the path from a chaotically dispersed, energy-disoriented form to a form”, is now the stuff of legend. Then there was his Fettecke, (Fat Corner) which matured over nearly 20 years. The ten-pound lump of butter stuck in a corner of his Düsseldorf studio was scraped away a few months after Beuys’s death in 1986 by an overzealous janitor, who noted at the time it had begun to “smell rancid”.

Remnants of Beuys’ “Fettecke,” which was scrubbed away by a janitor a few months after his death.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Rolf Vennenbernd

Also anchored in the collective memory is the Filzanzug (Felt Suit), one of Beuys’ most famous sculptures, created in 1970. Beuys frequently employed felt, noting it represented an insulator in which thermal energy – for him a driver of creativity – could be stored. Beuys not only built works of art out of felt and fat, to which he also attributed heat-storing properties, but also a legend: the story that he had supposedly been healed by Tatars with felt and fat wrappings after a plane crash in World War II. A myth, art historians say today.

Remnants of Beuys’ “Fettecke,” which was scrubbed away by a janitor a few months after his death.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Rolf Vennenbernd

Also anchored in the collective memory is the Filzanzug (Felt Suit), one of Beuys’ most famous sculptures, created in 1970. Beuys frequently employed felt, noting it represented an insulator in which thermal energy – for him a driver of creativity – could be stored. Beuys not only built works of art out of felt and fat, to which he also attributed heat-storing properties, but also a legend: the story that he had supposedly been healed by Tatars with felt and fat wrappings after a plane crash in World War II. A myth, art historians say today.

Beuys’ 1970 “Filzanzug” (Felt Suit) at the Neue Pinakothek in Munich as part of the “Ich bin ein Sender. Multiples by Joseph Beuys” (I am a transmitter. Multiples by Joseph Beuys) exhibition in 2014.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Nicolas Armer

Beuys’ 1970 “Filzanzug” (Felt Suit) at the Neue Pinakothek in Munich as part of the “Ich bin ein Sender. Multiples by Joseph Beuys” (I am a transmitter. Multiples by Joseph Beuys) exhibition in 2014.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Nicolas Armer

The living remains

So what is Beuys’ legacy after 100 years? Ina Conzen sees his contribution as a different understanding of art. She says that people have looked at art differently since Beuys, have allowed themselves to contemplate what art really is and whether it can change the world. Anyone travelling to or through the home of the documenta Kassel today will hardly be able to avoid one of Beuys’ living and enduring works of art and an example of his process-oriented concept of the “social sculpture.” The artist had 7,000 Oaks planted in the northern Hessian city during the documenta 7, planting first tree himself in 1982 and with the final tree planted by his son in 1987. It seems unlikely that these trees – and as such one of Beuys’ last works of art – will suffer a fate similar to that of the Fettecke and be rudely removed. They have been listed as historic monuments since 2005.