Freya Copeland

The Goethe-Institut New Zealand and Contemporary HUM present a series of portraits about New Zealand artists who have found a new home - also artistically - in Germany. Photographer MIchael Biedowicz talks to photographer and curator Freya Copeland.

By Michael Biedowicz

Freya Copeland (born 1990) is a young photographic artist who works with the photography medium in a multitude of different ways. After growing up in New Zealand, she now lives and works in Berlin and Valencia.

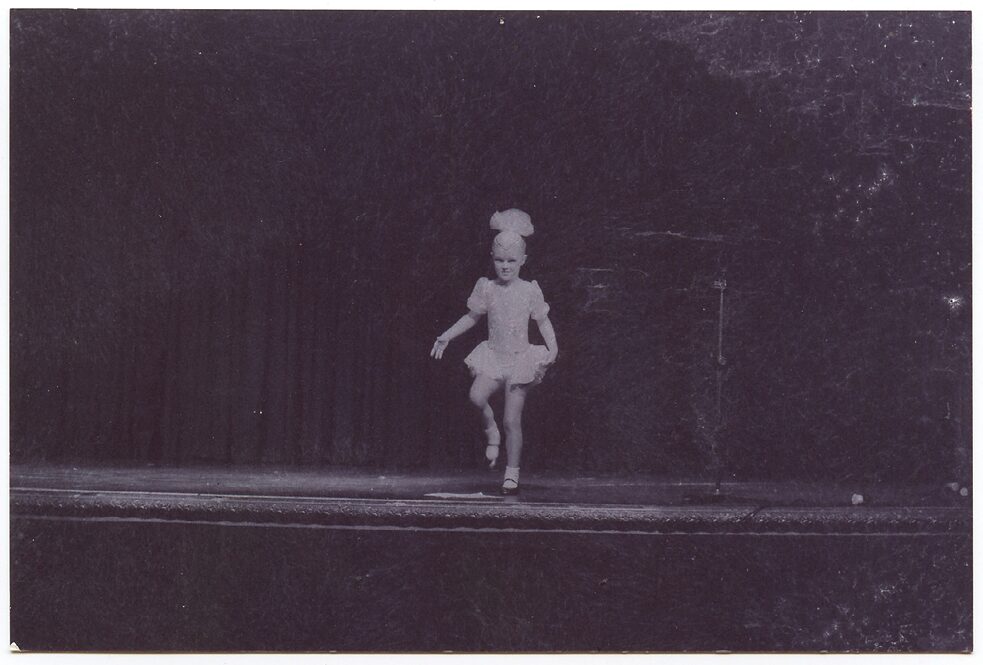

Freya’s engagement with photography began very early – when she was just 11 years old. Her first camera – an analogue reflex camera, which she still works with today – was a loan from her mother. While every artist’s first encounter with their art has a certain magic to it, in Freya’s case I quickly realised that this experience was a more fundamental one, a genuine revelation, developing into a passion that has continued to this day, driving her to keep coming up with new artistic conceptions. Her home environment was clearly a strong formative influence for the future artist.

The young Freya’s innumerable notebooks record all the reproductions of art works that caught her interest in the art books she borrowed from the Auckland public library, which she later tried to track down as originals. This inevitably prompted an interest in the issue of the provenance of artistic works, and raised the question of why European art was so omnipresent, including on foreign shores, and why there was not enough appreciation of the art of the Māori and of the Pacific.

Since 2011 Freya has been studying photography in Berlin, while also working as a curator and establishing the REPLIKA independent photography book publishing house, together with Youvalle Levy. The firm provides a vehicle for publishing her own works, and also those of other artists. Along with its function as a publishing house for art books, REPLIKA aims to provide a cultural home and support base for a new generation of young photographers keen to experiment with new ideas.

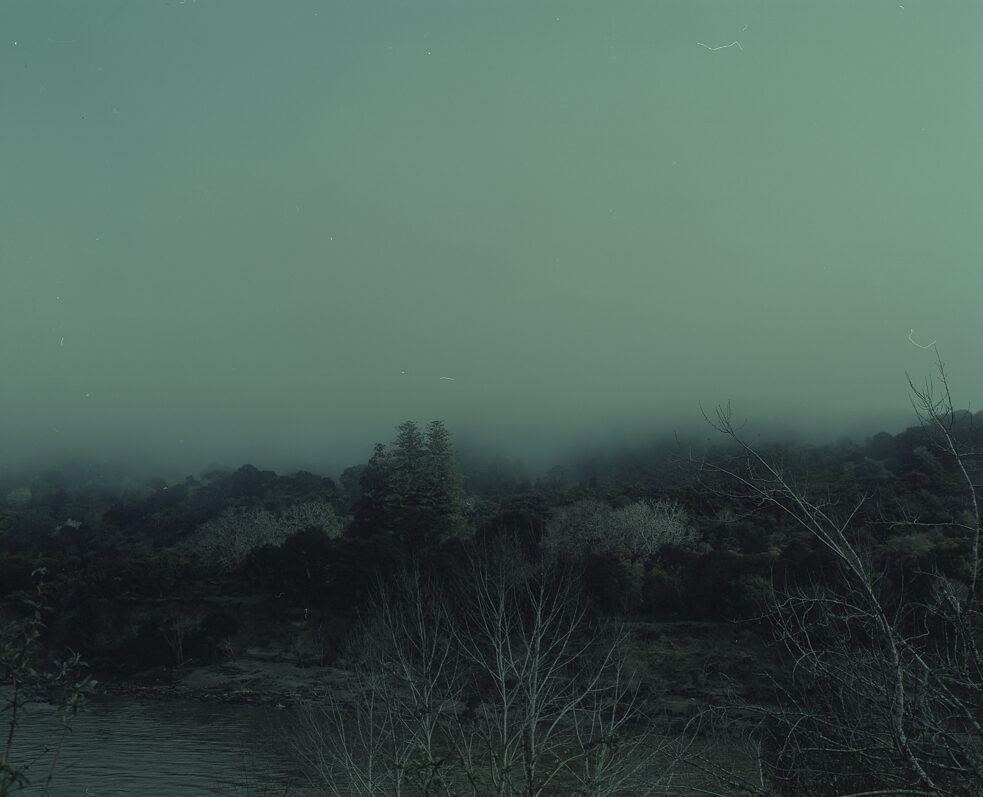

Freya’s work is characterised by an intensive interrogation of and reflection on topics that come with the times we live in, often addressing issues of isolation and the sense of being lost in urban environment, and the loss of a sense of belonging. Her focus on these themes can partly be attributed to a constellation of circumstances in her biography – born in Europe, she grew up in New Zealand and was largely formed by New Zealand culture, before returning to live in Europe.

The uncompromising aesthetic of Berlin’s streets and city squares and the unique hard light of the Berlin environment is strongly reflected in the aesthetic of her photographs, and is part of what drives her efforts to reveal structures lying below the surface and to delve into the history of this place. Freya describes the light in New Zealand in very different terms, as a uniform, ozone-free South Pacific glow. The constant and unquestioned presence of this light sometimes has the effect of concealing rather than revealing the stories and histories of this very different environment.

Her artistic projects extend far beyond simply producing photographs and series of images. These are rather just the point of departure of a process targeted at an active and empathetic observer. This is less daunting than it sounds – Freya Copeland’s approach to photographic statements, the way in which she plays with and constantly interrogates perceptions of fiction and reality are above all refined and reflective. What do we see in an image – do we all see the same thing? To what extent do our personal experiences and recollections inform our gaze, and how – and with what – do we fill in the gaps manifestly present in the narration of the work?

When working with her photographs, I have found myself wondering when she sees a work as finished and completed. From my perspective, this stage was reached once the photograph had been taken, or at the very latest when the work was presented to the public. But for Freya Copeland this is a dialogic process, with creator and observer each defining the other.

There are three parties involved in a photographic work: firstly, the person or object we see in the image; secondly the photographer as the creator of the image; and thirdly, lagging far behind, ourselves, the people looking at the work. Art history generally has little to say about this third category. But by bringing us, the people who view her works, into her photographs, Freya Copeland broadens the usual one-dimensional route from sender to recipient in a manner that is both pleasurable and inspiring.

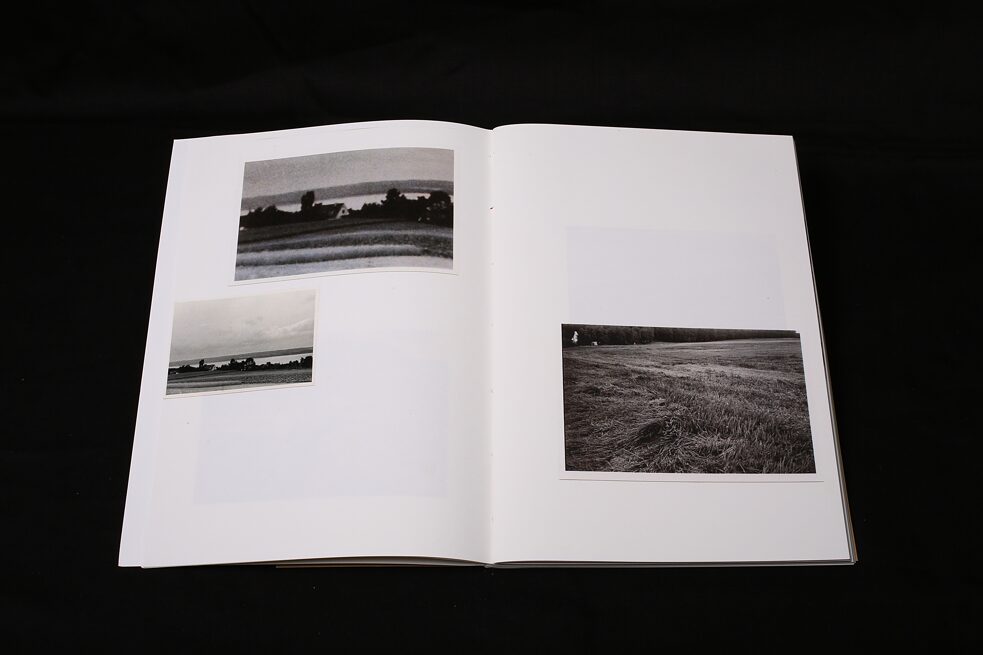

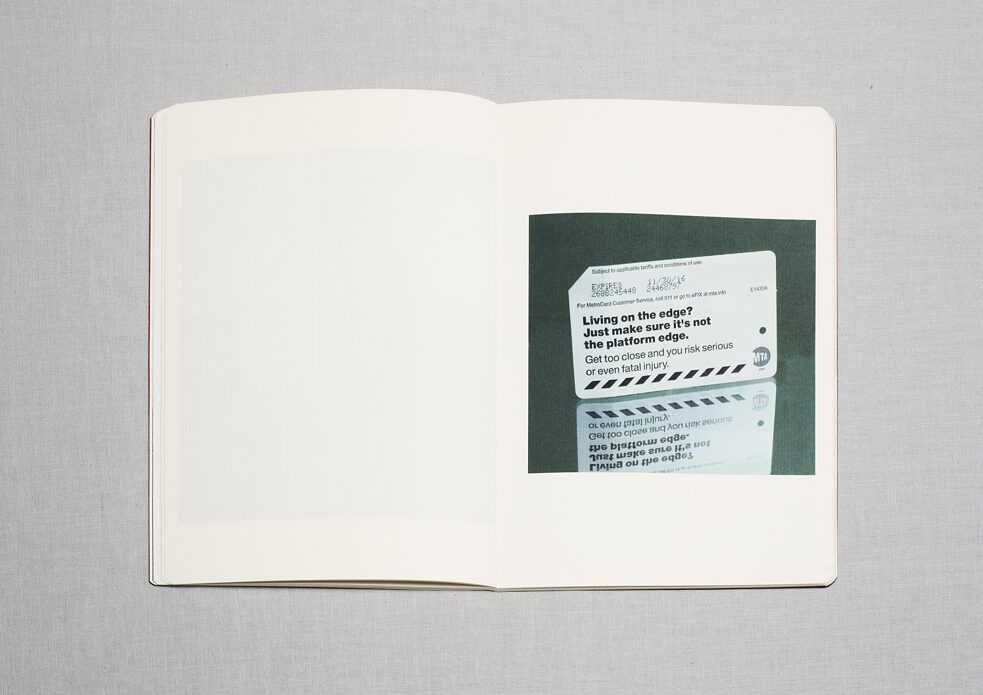

Her photographs are optimally presented in installations and above all in publications in book form, more specifically “artist’s books”. In the “Footfalls Echo” project, the book design deliberately replicates the form of a diary, as a very personal record of (city) spaces and the artist’s thoughts. The latter in particular are given plenty of space, both figuratively and literally, with a generous white margin left around the photographs in the publication, giving the images room to breathe. And not least, here I also see a commitment to beauty in photography. Her photographs in this work often show an empty space – and that in New York City! But it is quite true that one can feel alone even in the most highly overpopulated metropolis. The title refers to an echo, the echo of footsteps. For her, then, the echo that comes after the sound is placed in the foreground, and hence in the title. Reflection becomes the very subject of the work.

Another affinity of this artist is displayed in her work with archives and archive systems, as in the ensemble “Archive of the Arcane”. Along with made and found photographs, here we see all manner of artefacts, newspaper reports and notices – a wide selection of media materials that are generally regarded as fulfilling a documentary function, called upon to bear witness but left without any form of contextualisation. According to the artist, “my main aim in this project was to archive the unarchivable”.

She believes that culture and art history need these locations – archives, collections and museums – as places of memory and conservation/preservation. Yet almost no-one knows how they might and should be made to operate in a fully satisfactory manner. Shortcomings are inherent in the process, as lamented for example by Christian Boltanski, an artist whose oeuvre will forever remain associated with his work with archives.

His thesis is that the papers of a deceased person can never be fully processed and edited – the last piece in the jigsaw needed to decode specific facts and events is forever lost. The only option remaining for us as viewers is to order and interpret the photographs and documents for ourselves. In the words of Christian Boltanski, “I believe that each of us has a locked door before us, and everyone is looking for the key to unlock that door. All of us are looking for it! Some believe they have found it. But for me, the door will never be opened, for me there is no key that will fit, yet to be human means to keep looking for that key.”

This is the quest that Freya Copeland invites us to undertake.