Forbidden Films in the GDR

Portentous for Art

The eleventh plenary session of the Central Committee of the SED (the Socialist Unity Party of Germany) took place in Berlin in December 1965. This party conference is regarded as one of the most important watersheds in GDR cultural history. Leading SED party officials ranted about “decadence” and “scepticism” in literature and film, resulting in a whole wave of prohibitions.

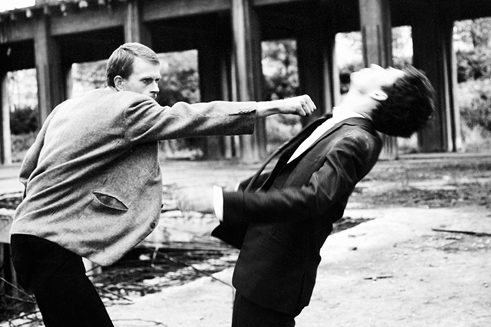

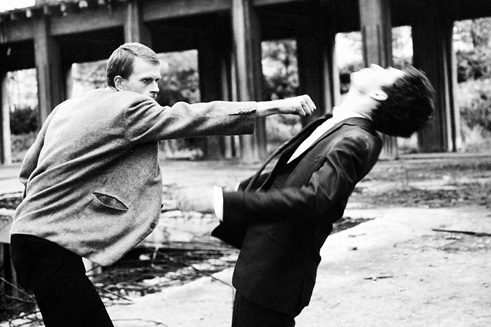

“We are all slaves!” is emblazoned in luminous white paint on the wall of a factory somewhere in East Berlin. It was written by two youths who were full of anger and frustration at the bureaucratic conditions which prevailed at their workplace and the patronizing attitude of their older colleagues. It was not only their working conditions against which they were protesting, as the statement served at the same time as a synonym for their entire lives – lives shaped by ideology, the impositions of the state and socialist plan fulfilment. What they wanted was for all of this to come to an end at last. – The scene is from Berlin um die Ecke (1965), a DEFA film directed by Gerhard Klein and written by Wolfgang Kohlhaase. It was so realistic that it could equally well have actually happened. Indeed it was too “realistic” for some SED party officials. In the autumn of 1966, Berlin um die Ecke was banned because of this and other “subversive” scenes which failed to paint a glorified picture of everyday life in the GDR (German Democratic Republic) and instead made unvarnished reference to contradictions and problems. It was not until several decades later that it was allowed to be shown for the first time.

Trailer: “Spur der Steine” | © DEFA-Stiftung, via youtube.comBerlin um die Ecke was by no means an isolated case. As a result of the eleventh plenary session of the SED’s Central Committee, a dozen DEFA films were banned or had their production discontinued in a move which went down in GDR history as a “Kahlschlag”, a word used in forestry to denote total deforestation. Among them were some of the best DEFA films ever made, for example Spur der Steine (1966, directed by Frank Beyer), Karla (1965, directed by Herrmann Zschoche), Das Kaninchen bin ich (1965, directed by Kurt Maetzig) and Jahrgang 45 (1966, directed by Jürgen Böttcher). The wave of prohibitions brought a brutal end to a unique artistic revolution in East German filmmaking. What many of the banned films had in common was their desire to make a difference: they criticized social conditions in the GDR, but in an attempt not to abolish socialism but to “improve” it. It was not only the socially critical undertone of some of the films which was chiefly responsible for their prohibition, but also discord within the SED party leadership as to how the GDR should develop in future.

Artistic departure towards socialist modernism?

After the Berlin Wall was built, the East German government led by Walter Ulbricht had initially proposed a variety of reform projects. The SED leadership also embarked on a new approach in its youth policy. In the “Youth Communiqué” it announced in September 1963, the SED hinted that it intended to grant youngsters in the GDR greater personal freedom and allow them to pursue an alternative lifestyle. This development was also reflected in the cultural domain: until the Wall was built, many GDR artists and intellectuals had moved to the West in order to escape the repressive policies of the SED. Other artists had taken a conscious decision to remain in East Germany on account of their political convictions, however. They hoped that it would now be possible to play an active part in shaping a socialist society. It seemed that existing problems and deficiencies could be openly discussed. Artists were cautiously optimistic that change might be in the air.Whereas the reform policies met with a very positive response among the population, the liberal tendencies were controversial within the SED leadership right from the outset. The dogmatic SED party officials were opposed in particular to the more permissive western-style youth culture. The fact for example that many young people in the GDR were interested in beat music and started their own bands which became extremely popular was not tolerated for long. The beat groups were banned, their fans vilified as “yobs” and treated like criminals.

A symbolic conference

The SED finally renounced its liberal cultural and youth policy at the eleventh plenary session of the Central Committee from 15 to 18 December 1965. Leading party officials such as Erich Honecker, Paul Fröhlich and Paul Verner made indignant speeches about the “immoral” behaviour of young people in the GDR. They had already identified who was to blame: artists. With their “bourgeois scepticism”, writers and filmmakers were accused of disseminating a “culture of doubt” in the GDR and of inciting young people to violence. It was above all the writers Wolf Biermann, Werner Bräunig and Stefan Heym who came under fierce attack at the plenary session. Criticism was also focused on the feature films Denk bloß nicht, ich heule (1965) by Frank Vogel and Das Kaninchen bin ich by Kurt Maetzig. They were presented to the assembled party members as particularly “damaging” examples and reviled as “botched counterrevolutionary attempts”.This harsh criticism of culture came at just the right moment for the dogmatic SED officials. They exploited the critical engagement with artists to speak out in fundamental terms against all liberal tendencies in the GDR. As such, the eleventh plenary session was also a symbolic discussion about the future political development of the GDR, a debate which saw the critics of reform-oriented policies prevail. Many of the arguments they raised against the artists were “merely” a pretext: the two DEFA films for example had not even been shown in public yet, and as such could not have had any negative influence on East German youngsters. The texts by Biermann and Heym which expressed criticism of the system were not allowed to be published in the GDR, either. The main reason for both being attacked as enemies of the party at the eleventh plenary session was the fact that they had published their works in the West, which in the eyes of some SED officials counted as “betrayal” of socialism.

A wave of prohibitions

The eleventh plenary session had a far-reaching impact on artistic development in the GDR. Some socially critical novels and theatre plays were not published, while numerous artists were banned from pursuing their professions or performing. The DEFA, the GDR’s nationally-owned filmmaking company, was particularly hard hit by the repressive policies. All feature films that were planned at the time were checked for ideological content. The wave of prohibitions continued until the autumn of 1966 and marked one of the most radical watersheds in East German film history. Socially critical topics could only rarely be tackled in the following years, and the banned films themselves almost all remained under lock and key until 1989/90.Andreas Kötzing, Ralf Schenk (Hrsg.): Verbotene Utopie. Die SED, die DEFA und das 11. Plenum, Berlin 2015