- How to Create Another Society

- Industrialization of Space and Housing the Masses

- Industry

- A New Way of Life

- Arts and Culture for the Masses

- Leisure and Free time

- Built Ideology

- German-Soviet Relations

- Soviet Orientalism

- Parallel Ideology

- Organization of Everyday Life

- Science, Technology, and Progress

- Sports and Physical Culture

How to Create Another Society

The ideological call for modernization of the USSR and a radical different idea of a collective society in the 1920s led to new typologies for city plans, infrastructure, mass housing, public buildings, and edifices of political representation, for working, celebration, and recreation in a radical, modernist language. This resumed after 1955. Architecture responded with new and singular typologies – from the pioneer camp to the houses of creativity, from the circus to the wedding palace and grand prestige projects and monumental buildings that aimed to represent the Soviet concept of a new socialist society. However, under Brezhnev, Soviet society as a whole adopted a westernized lifestyle, putting the decline of the communitarian ethos of Soviet ideology into stark relief. In the end they remained imposing gestures whose symbolic integrational power was not enough to secure the system’s legitimacy. The insoluble contradiction between the imaginary space of symbolic political authority and the real space of everyday life likewise contributed to sounding the death knell of the Soviet empire.

Industrialization of Space and Housing the Masses

In the late 1950s, Soviet architects and engineers developed technical systems for the off-site fabrication of housing systems at industrial factories, based on the production of standardized panels and other prefabricated elements. One such system, the I-464, developed in 1958 by Giprostroiindustria, was capable of delivering complete residential blocks from just 21 prefabricated components. Factories producing these components became widely used in the Soviet Union and were replicated to accommodate millions of families. They disseminated across the most distant regions, from Tallinn to Vladivostok and emerged in both urban and rural contexts, beyond the Arctic circle and in the Soviet Union’s southern republics. From the early 1960s, as a result of the politics of socialist internationalism, these factories were also exported to foreign countries, both capitalist and socialist, including Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Cuba, and Chile. In each of the locations, the design of housing was adapted to make the system fit local climatic and seismic conditions. The complex work of adapting standard housing design was done in experimental micro-regions, as part of a constant process of ongoing development. By the end of the 1970s, large-panel housing included a substantial offering of national-specific projects, which enabled a great diversity in possible urban development. With the pictures of regional variations, as well as exported projects, in foreign countries, this station presents large-panel Soviet housing as a truly global phenomenon.

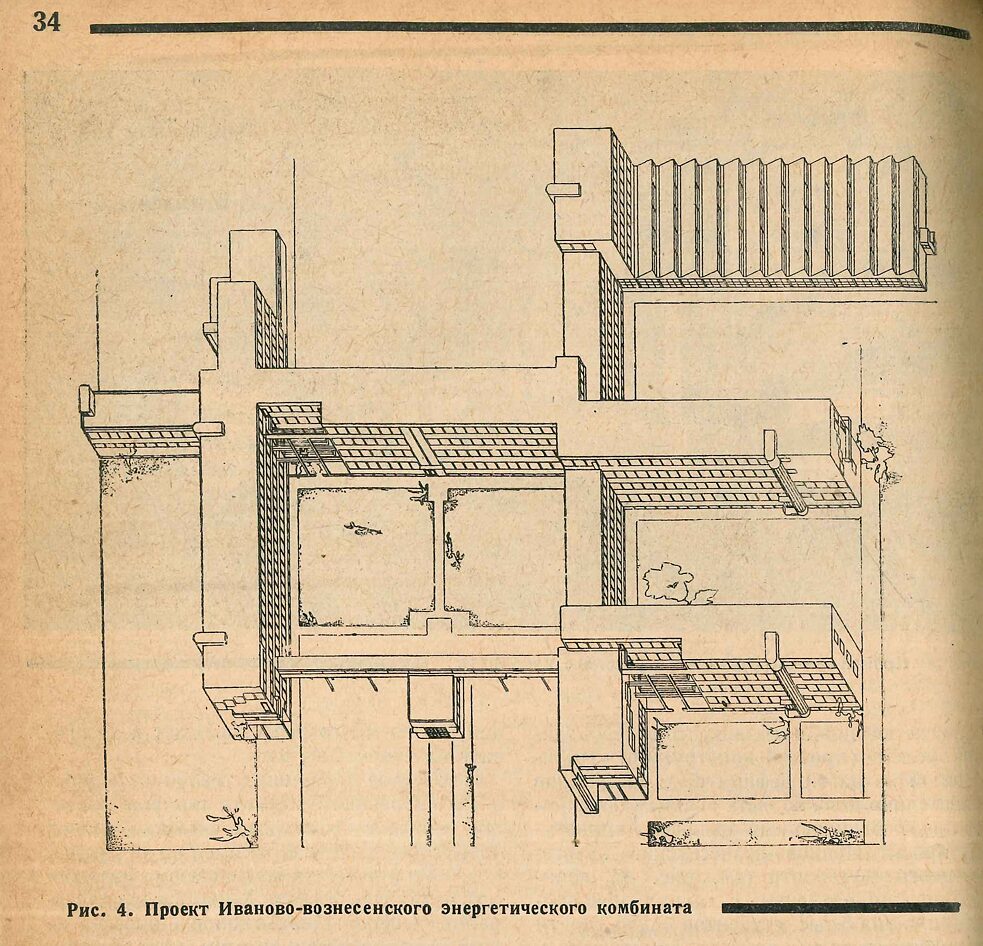

Industry

Industry played a major part in the economy of the USSR throughout the country’s history, making industrial architecture a high priority for the Soviet state. Yet, many Soviet industrial facilities and projects were classified confidential and, as such, rarely made it to the pages of architecture magazines. Even today, access is restricted to many of the industrial facilities, an obstacle preventing researchers and historians from studying this heritage. This is the chief reason why Soviet modernist industrial architecture is barely known or studied. Thesis projects, written by students from the Department of Industrial Design, are among the few sources that shed at least some light on this facet of the USSR’s architectural legacy.

From the 1940s onward, nuclear power was seen as a unique industry within both the Soviet economic system and the country’s official ideology. In the 1960s, this energy was promoted as the so-called ‘peaceful atom’ that would produce enough electricity for the world’s largest country, improve its economy, and eventually help communism overcome capitalism as the two world orders co-existed peacefully. However, with the Cold War constantly threatening to escalate into World War Three, nuclear power was increasingly perceived as a threat to human life. Both of these sides to nuclear power were manifested – often without architects fully realizing the fact – in the designs of nuclear power plants created by students from the Moscow Architecture Institute in the 1960s. These projects celebrated the magnificence of the latest scientific breakthroughs, while also being overshadowed by the possibility of a catastrophic tragedy, which became reality in Chernobyl in 1986.

A New Way of Life

The Soviet state regarded its post-war mass housing campaign as more than just a functional imperative to achieve cost-efficient standardized construction. In the Khrushchev era, domestic space, as an important site for everyday life and mass consumption, became the object of intense professional and public attention. Authorities in charge of housing design considered multiple social and aesthetic questions about the organization of everyday life, focusing on the Soviet family as the central subject of this process. The requirements, needs, desires of the family, its varying sizes and structures were closely scrutinized and considered in the typological research and planning of housing layouts and residential areas. A set of standardized apartments were developed to accommodate families of different sizes – from so-called ‘small families’ with one or no children to large nuclear families with several children. The domain of sociology became a central mediator between architects and the family. Providing architects and planners with a unique entryway into the world of the family, sociological discussion in the 1960s included broader questions about everyday life under socialism. Housing designs, such as the House of the New Way of Life were made so as to offer family life the option of socializing with neighbors during certain hours (meals, collective leisure), while also offering solitude at other times.

Arts and Culture for the Masses

The liberalization of Soviet society, beginning with the Khrushchev ‘Thaw’ in the second half of the 1950s, brought with it a new energy and experiments in almost all fields of culture: the “Sweet Sixties” started. The onset of the Brezhnev era marked the decay and death of this opening of possibility – the end not only of the Prague Spring in 1968 but also of a brief flowering of progressive, officially-sanctioned youth culture across the Soviet sphere of influence. The official normative aesthetic was restored, and alternative movements were suppressed.

As a result, official art became more and more formal and soulless. In contrary to the revolutionary constructivist 1920s, an eclectic and tamed modernism was taught in the conservatoriums, the new Children’s Music and Art Schools, and was performed in the new theaters, concert-halls and event centers that were built throughout the Union. The revolutionary idea of establishing a new form of proletarian culture, which had been curtailed by the Socialist Realism of the Stalin era, now returned with a different aesthetic program – a culture of classical education and mass spectacle, such as large-scale performances of folk culture that articulated the official party line: ever-growing joy and optimism of Soviet life, loyalty to the country, Lenin, and the Communist party. Yet from the mid-1960s on, a counterculture, an unofficial private and underground sphere emerged, in which – spied upon by the KGB – the avant-garde of late socialism found shelter and display until the illusions and post-modern euphoria of the Perestroika years arose.

Leisure and Free time

The ideologists of late socialism developed a new concept of a “socialist way of life” whose chief distinguishing features were affective and moral. This took place in the late 1960s and 1970s. Many events organized by the work collective or the party state offered forms of ritualized leisure-activities. Space for free time was reserved in the town planning of the microraions: There were parks, playgrounds, garages and special settings for communication. Canteens and cafés were available for getting a quick meal, while restaurant dining was strictly regimented and extremely costly. The government even conceptualized consumption as a social right of its citizens. However, there was a lack of consumer goods.

Manageably sized residential districts were designed to deepen the interaction between residents, representing the Soviet variation on the neighborhood concept. Self-administration institutions, such as “Residential Offices”, tried to promote a collective form of living. But, just like in the West, social reality presented an entirely different picture. Most residents tried to evade state control. Everyday social life in most households was dominated by family and friends, self-made communities that did not correspond to the structures of the microraions and the many circuses, mega-cinemas, memorial parks, chess houses, etc., that emerged in this period.

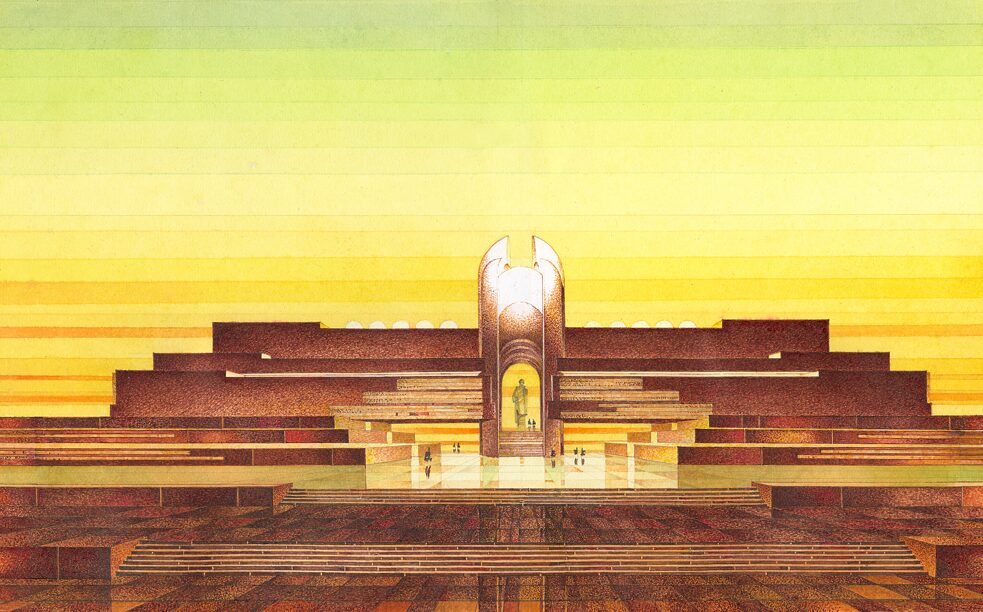

Built Ideology

Akey concept in post-Stalinist Soviet urbanism was to create celebratory spaces that would simultaneously reinforce the unity of People and Party. To that end, the state and Party leadership continued to prioritize mega-projects and grandiose edifices. Large-scale rallies and parades were staged across Soviet cities, emphasizing the ethos of collectivity and thus legitimizing the rule of the Party. For this type of public manifestation, correspondingly spacious boulevards were required to serve as marching grounds. Around vast public squares – which were supposed to form political hubs for the citizenry, but actually had the effect of generating a feeling of individual helplessness in the face of such expansive state authority – government and Party buildings, Lenin Museums, cultural palaces and monuments were grouped.

German-Soviet Relations

The 1917 revolution turned the former territories of the Russian Empire into an experimental site for construction of the new world. By the mid-1920s, Soviet modernist architects had established contacts with European colleagues. Moisei Ginzburg from the Constructivist OSA group played an important role in arranging these ties, which evolved into a close cooperative relationship particularly with Germany, where a housing crisis catalyzed intensive research into rationalizing design and industrializing construction. The Bauhaus school at Dessau became the symbol of these aspirations. At the same time, the large-scale application of new building principles took place in Frankfurt-am-Main, where Ernst May lead the rapid construction of several standardized settlements.

In the beginning of the 1930s, the Soviet government invited Ernst May, along with other architecture and design experts, to work on the rapid construction of cities and settlements to serve newly established factory complexes. Among those experts were architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotsky, famed for her design of the functionalist “Frankfurt kitchen,” her husband Wilhelm Schütte, architects Mart Stam, Hans Schmidt, and many others. Several architects and designers related to the Bauhaus would also arrive, for example the second director Hannes Meyer and some of his students. They were involved in planning dozens of cities and buildings, but also contributed to establishing modernist design principles within the Soviet sphere of influence that, with all of its advantages and disadvantages, defined the architectural landscape of the country for most of its existence.

By the end of the 1930s, foreigners were removed from significant posts in Soviet society. Many architects from abroad who stayed or had to stay in the country were jailed or killed during the Stalinist repressions. A rare few, for example Philipp Tolziner, managed to survive those years and continued their careers as employees of design institutes and ateliers.

Soviet Orientalism

The modernists intended to create a universal language suitable for any local context, but this task was considerably complicated in the conditions of Soviet Central Asia and, to a lesser degree, in the Caucasus. On the one hand, the planning authorities and the architects themselves, mainly from the European part of Russia, exported models of city-building that were developed in Moscow. On the other hand, it was assumed that the building of socialism in places where the majority of the population followed Islam or led a nomadic lifestyle should be carried out through the creation of nation-states on the European model, their cultural institutions and specific architecture designed to serve and represent the imagined community. These directives on the formation of nations and their social modernization were often associated with the exoticization of the image of local ethnic groups, in turn reproducing European orientalist clichés. In this context, architecture had to play a dual role; it had to reflect an imaginary “national mentality”, but it was also considered as an effective tool for changing the cultural habits and traditions necessary for the formation of the “socialist nations”.

Parallel Ideology

Though decision-making authority in Soviet architecture was ostensibly centralized in the Moscow bureaucracy, regional and local authorities had a certain degree of liberty with regard to construction and design decisions. Decrees about planned projects and their funding were issued in Moscow, but in actual administrative practice the regional apparatuses were able to maneuver to have final authority over how the available resources were put to use. By means of falsified reports and other deceptive mechanisms, local functionaries were able to give their own priorities precedence over those of the central regime.

In various Soviet republics, particularly in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Baltics, such practices gave rise to more idiosyncratic architectural styles that sought to synthesize elements of vernacular architecture and national tradition with the formal vocabulary and industrial construction practices of modernism. Architects chose to draw on “historical roots” not only as a critique of monotonous functionalism, but also due to the influence of burgeoning nationalist ideologies in the respective republics.

Organization of Everyday Life

The panelized concrete mass housing developments on city outskirts were built to encircle the dramatic settings in the city center. While the urbane socialist elite, such as politicians, members of the military or intellectuals, lived in prestigious buildings typically located in the city centers, the masses were housed either in communal shared apartments or in huge new developments on the urban outskirts. The development of transport infrastructure and of social facilities lagged behind the dynamic growth of these peripheral areas. An important basis for city planning was provided by the “Rules and Norms for Urban Planning and Development” instituted in 1955, which held that cities should be divided into different functional zones, for living, industry, traffic, and communal service facilities, separated from one another by green areas. Several microraions were in turn united to form a residential zone with its own shops, clinics, and cultural centers, whereas the city centers covered the more specific needs of residents: department stores, theaters, hotels, and schools.

Science, Technology, and Progress

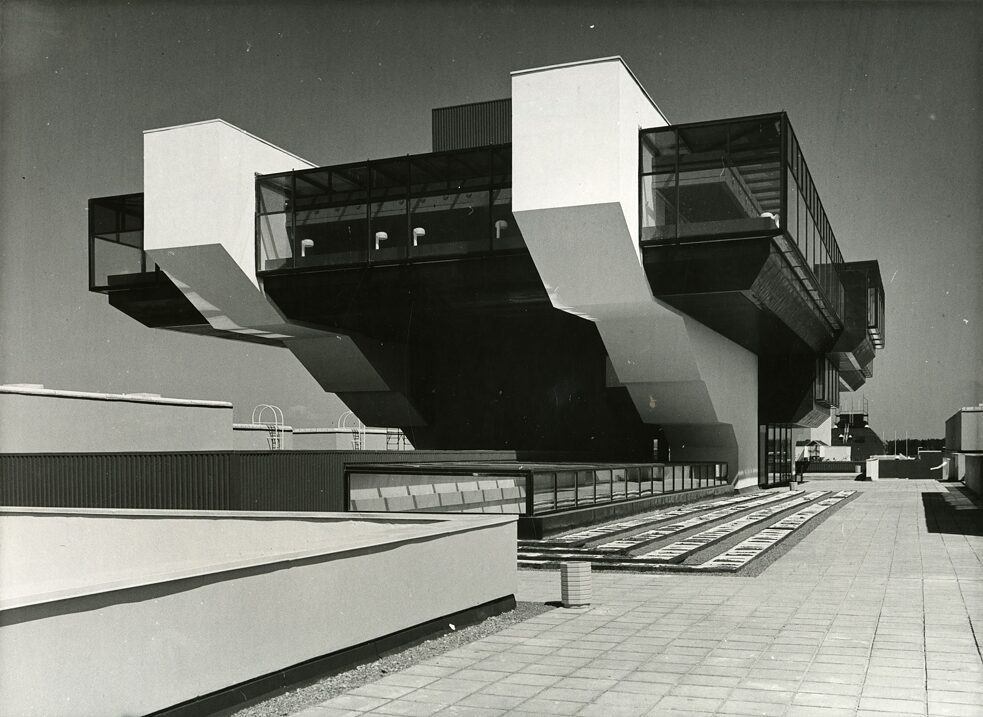

In the Cold War era, the Soviet government made the cultivation of scientific and technical expertise a national priority of the highest order, lauding research scientists with prizes and honors. The discipline’s core institution was the Academy of Sciences, which contained 250 research institutes and 60,500 full-time researchers in 1987. In all the republics, new research institutes, universities, and architectural institutes were founded and educated an increasingly self-assertive local elite.

The Kremlin gave scientists, technicians, and architects the resources to modernize their respective disciplines and to imitate or build upon Western European and American developments. During this period, dozens of closed cities were built around the country for the purpose of conducting covert research. Some were naukogradi (“science cities”) or akademgorodki (“academic cities”), while others developed military technology, nuclear reactors, and, later on, spacecraft.

While the Communist Party remained restrictive with regard to any creative deviations in the visual arts, modern architecture—a scientific discipline since it was regarded as an ideology-free technology—by contrast was largely given free rein. This is evident in the experimental character of many of the structures built for science and technology after 1955.

Sports and Physical Culture

Sports played a major role in the USSR during the post-World War II period. Soviet leaders saw physical culture as an essential element in the construction of socialism and the creation of “Homo Sovieticus.” A healthy and fit population represented an important resource in an age of large-scale industrial manufacturing. Additionally, Soviet ideology of the period saw physical culture as something that would create harmonious individuals, in mental and physical equilibrium with themselves.

Gymnastics and sports festivals, as well as the quadrennial “Socialist-Olympics”, known as the Spartakiadas, were among the most visible public events in the Union (in addition to party rallies, military parades, and marches). The achievements of Soviet athletes in the international arena, particularly in the Olympic Games, were a source of great national pride (therefore, the West’s boycott of the Moscow Olympics 1980 was seen as an aggressive act of humiliation.) The many stadia, sports arenas, and multifunctional sports and entertainment palaces belong to the most impressive and technologically advanced structures built in the late Soviet Union.