By Dmitry Sadorin

At the Werkbund Exhibition in 1914, the clash between Henry Van de Velde and Hermann Muthesius outlined the principal fissure in the Modernist Movement for decades to come. While Van de Velde defended individualism as a stronghold of architectural quality, Muthesius advanced the idea of standardized forms as the only possible solution to the challenge of mass production in construction. Indeed, in all arts, modernism was about finding an individual style, and it is through the ‘pioneers’ that the history of the Modernist Movement has been told. Yet after World War II, it was highly rational, bureaucratic modernism that conquered world architecture, and housing construction in particular.

Nowhere was the impact of unification as strong as in the Soviet Union, where housing estates built from standard blocks swallowed whole cities. The exceptions were rare, and mostly manifested in unique public buildings. Minsk took a different road and managed to generate individuality from the sheer combination of standard blocks, thus reuniting the Werkbund’s visions of modernism under the flag of mass housing. Praised by the architectural community all across the USSR, several of Minsk’s housing estates became known as the Minsk Phenomenon.

Exhibition

The exhibition is set to show the achievements of the Minsk Phenomenon as the synthesis of the extremes: of the Soviet standardized forms on the one hand (thesis) and the riotous search for extreme individuality on the other (antithesis). The exhibition is subdivided into the following three sections:

Belarusian Modernism: Six States of Modernism

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Minsk was the fastest growing major city in both Europe and the Soviet Union. Its small old core was quickly swallowed up by endless outskirts, and despite the Minsk Phenomenon, the Belarusian capital was desperate to look for resort in non-residential buildings. Every non-standard structure had to become a monument to its own uniqueness. However, building the new country was accompanied by the deconstruction of its progressive past. Even though Belarus might be regarded as a safe haven as compared to other former Soviet republics, it still destroys, mutilates, encapsulates (a strikingly local phenomenon!) great examples of Soviet Modernism, leaving others in constant danger of falling into the hands of refurbishment and investments. Benevolence is not always beneficial, let alone sheer disdain for the city and its heritage. Some buildings and complexes linger on in neglect and a lack of alternatives, and only a few have been elevated to a new level and enjoy the appropriate recognition.

Minsk Phenomenon

After the Second World War, Belarus at length embarked on a belated industrialization. With little national flamboyance in the spirit of Social Realism to fight for, the republic excelled in constructing its identity through condensing Soviet ideals. Belarusians shaped new Soviet pastoral in experimental villages, livened up the industrial periphery by uniting factories into giant nodes and, for their capital, developed a perfect concept of the Soviet residential environment. The latter, known as the Minsk Phenomenon, stood for unique imagery and endless diversity in the planning of residential estates, achieved through the deployment of standard designs and block-sections. The Minsk Phenomenon was claimed to be the product of an intense and successful collaboration between architects, builders and authorities. If any of the actors were missing, the union would collapse, and appalling dullness would recapture the city’s urban periphery. But this is what happened, as architects, starting from the mid-1980s, fascinated by postmodern critique, turned their attention away from mass housing. Now standard architecture was believed to pervert the idea of social modernization and progress, by ignoring human scale and the historical and cultural context. The Minsk Phenomenon was dead. Later, at the turn of the millennium, when the strengthening independent state decided in favor of an ideological resuscitation of mass housing, re-industrialization in the field started. However, still disdained by the architectural elite, mass housing seems only capable of fulfilling its social role—a hint that the Minsk Phenomenon was not a product of unique collaboration, but a whim of individual great architects. But if the path of housing construction industrialization is walked anew, and history repeats itself, is there not hope for a new Minsk Phenomenon?

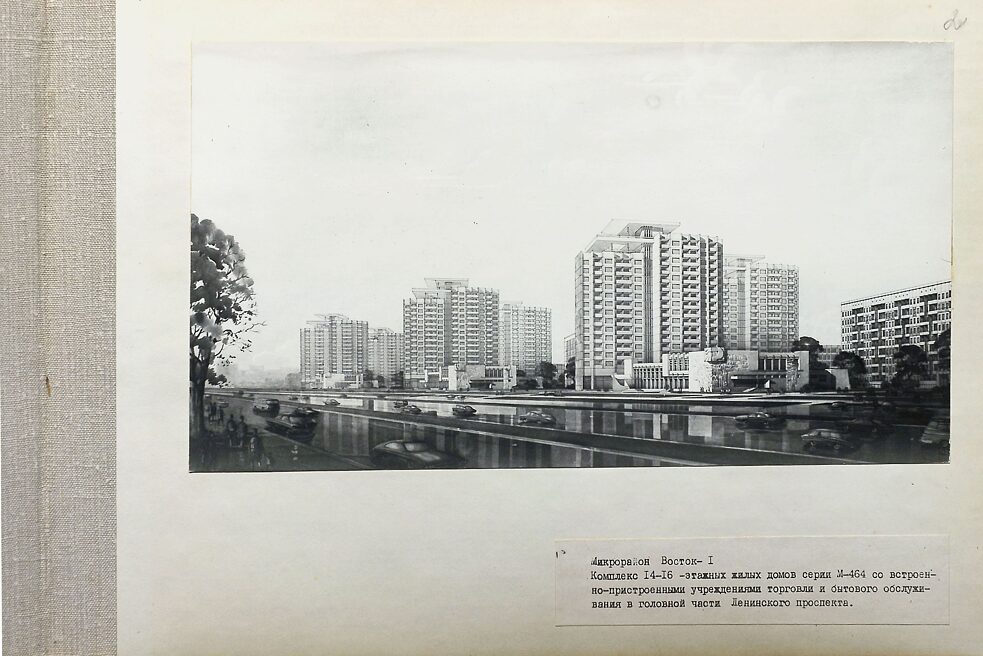

Minsk Phenomenon Hardware

The very definition of the Minsk Phenomenon presupposes a strict opposition between the diversified urban environment created in the Belarusian capital, and factual apartment blocks—highly standardized elements from which the city’s estates were composed, or in short between what we call ‘software’ and ‘hardware’. And indeed, at the architectural level, Minsk apartment blocks differed little from those in other cities. Their main distinguishing mark was the highest quality of construction across the USSR, for which Minsk house-building plant No. 1 won repeated awards. In any case, the success of the phenomenon was tightly bound to a number of local construction systems, or series, that were developed specifically for the Belarusian capital by Minskproyekt and Belgosproyekt from the late 1960s onwards. Enveloping the city in a cobweb of worm-like buildings, the three large-panel series made it well into the independence period. They have proved so successful that, somewhat modified, they still form the backbone of residential construction in the city.