The sugar cube

From round to square

In Datschitz in the Czech Republic is a monument that shows a sugar cube. Why? Because Jacob Christoph Rad invented it here. Later a Frenchman, then a Belgian, perfected his idea – which had been brought about by a coincidence. Or rather, an accident.

With or without sugar? This question splits coffee and tea drinkers into two camps. Those who prefer their drink with sugar find it in all sorts of variants: brown or white, from the shaker, out of a sachet - or just as a sugar cube. The sugar cube has even its own monument: a granite pedestal on which a white cube is balanced on just one corner. So it stands in Dačice (Datschitz), a city at the southernmost tip of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands. An exhibition in the local museum reminds us that the sugar cube first saw the light of day here.

In the beginning was … the injury

As with many other inventions, coincidence played a part here – or rather, accident. On an August day in 1841, Juliana Rad injured her finger while chopping off a piece of sugar loaf. No wonder, seeing as the impractical sugar loaves were not only hard but also one and a half metres high! If you needed sugar, you had to help yourself with hammer, pliers and crowbar. The disgruntled Juliana told her husband to find a simpler way of getting sugar than the laborious and dangerous hacking. And because her husband happened to be Jacob Christoph Rad, the Austrian managing director of the local sugar refinery, and also an enthusiastic inventor, nothing stood in the way of the invention of the sugar cube.The steep way up

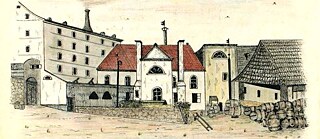

Whether her husband’s invention pleased Juliana is not known. What is certain is that Rad already asked the Court Chamber in Vienna at the end of 1842 to grant him special rights for the production of sugar cubes in Datschitz for a period of five years. He finally received the imperial and royal patent on 23 January 1843. In the same year, the novelty appeared on the market for the first time, called “tea sugar” or “Viennese sugar cubes”, and was successful straightaway. Sugar cubes were sold for 50 kreuzers; each pack of 500 grams was marked with a picture of the Datschitz refinery. The new form of sugar spread to western Moravia, eastern Moravia, southern Bohemia, and finally over the border to Austria.From France to Belgium

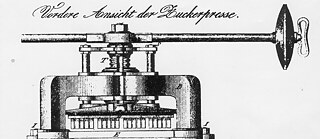

Although the machines were finally shut down in Datschitz in 1852, the sugar cube made its way through Europe - and was constantly evolving. Half a century later, the Parisian food manufacturer Eugène François built on Rad’s legacy with a machine designed for mechanically cutting and breaking sugar, since the traditional method of crushing of sugar seemed to him unhygienic. He continued to perfect his invention and patented it twenty years later.The history of the sugar domino continued in Belgium at the beginning of the twentieth century when Théophile Adant, a partner in the Flemish sugar refinery Tirlemontoise, developed a turbine for the production of sugar slices. Before crystallization of the substance, he poured the sugar magma into the turbine and the solid, dried sugar mass was then mechanically cut into smaller, practical bars and symmetrical cubes. An alternative method of producing cast sugar cubes, which were stored in prefabricated boxes of up to 25-kilogram, was in use until 1940 and made a name for itself in the history of sugar production as the Adant process. The company of the French mechanical engineer and entrepreneur Louis Chambon found in 1949 a way to make regular sugar cubes directly with the help of rotary presses by pressing moistened, ground sugar in the desired shape into them. Chambon’s method of pressing fine crystalline sugar is still used today in the production of sugar cubes.