Kafka and sport

The great swimmer

Most people know Franz Kafka as that brilliant author who wrote “Die Verwandlung” (The Metamorphosis), “Das Urteil” (The Judgment) or “Der Process” (The Trial). Then again, others value him equally for the elaborate sentimentality in his books. However, what many Kafka buffs don’t know: Kafka was a thoroughly physical person, Kafka was not just sporty, he was an all-out sports enthusiast. And – fun fact – his great nephew Martin Kafka trains the Czech national rugby team.

By Benedikt Maria Arnold

Franz Kafka used to go on long walks and hikes, went rowing on the Vltava, and played tennis. One notable way he found to counterbalance his depressing work was the “Müller” full-body workout. This term referred to a sport discipline fashionable at the start of the twentieth century and named after its inventor. At that time, Danish sportsman and gymnastics teacher Jørgen Peter Müller wrote a bestseller entitled My System. The book featured gymnastics and breathing exercises, and the Dane promised “Do this 15-minute workout every day and get fit and healthy!”

Kafka was impressed, and from 1910 onwards he did his “Müller” exercises with passionate commitment every evening for many years – kindly yet firmly recommending the method to his nearest and dearest. In a letter to Felice Bauer he writes encouragingly: “In a few days I will send you the ‘System for Women’, and slowly, systematically, carefully, thoroughly, and daily (for after all, you did promise, didn’t you?), you will begin to do Müller exercises, report on them continually, and so give me a great deal of pleasure.” All his insistent recommendations were of no use, in the end Felice Bauer did not buy the hype.

However a different physical activity played a far greater role in Franz Kafka’s life: swimming. Throughout his life, swimming was one of his greatest passions. In contrast to his hated everyday work routine, diving in and moving along in the water was a rare feeling of freedom for Franz Kafka. Being certain of an opportunity to swim was so important to him that he would enquire about local pools when he went travelling. Meanwhile he had an annual membership at the Prague Swimming School on the Sophieninsel – even when he was already suffering from tuberculosis.

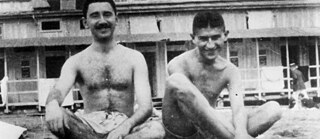

The fact that Kafka maintained such a positive relationship with swimming comes as a surprise when you look at his biography. As a boy, Franz’s father regularly took him to the “Civilian Swimming School” on the Kleinseitner waterfront. The head of the Kafka household – Franz would later refer to him as a non-swimmer – taught young Franz to swim there. In his Brief an den Vater (Letter to my Father), which has now become famous, Franz Kafka writes the following on the subject:

“I remember, for instance, how we often undressed in the same bathing hut. There was I, skinny, weakly, slight; you strong, tall, broad. Even inside the hut I felt a miserable specimen, and what’s more, not only in your eyes but in the eyes of the whole world, for you were for me the measure of all things. But then when we stepped out of the bathing hut before the people, you holding me by my hand, a little skeleton, unsteady, barefoot on the boards, frightened of the water, incapable of copying your swimming strokes, which you, with the best of intentions, but actually to my profound humiliation, kept on demonstrating, then I was frantic with desperation and at such moments all my bad experiences in all areas, fitted magnificently together. I felt best when you sometimes undressed first and I was able to stay behind in the hut alone and put off the disgrace of showing myself in public until at last you came to see what I was doing and drove me out of the hut. I was grateful to you for not seeming to notice my anguish, and besides, I was proud of my father’s body.”

Kafka addresses the subject of swimming considerably more enigmatically than in the letter to his father in a surviving fragment of text. In a piece of prose written around 1920, he tells the story of a nameless Olympic winner who set a world record in swimming and is then taken to his home town to celebrate. There, he attends a banquet held in his honour, and whilst there the swimmer quickly reveals that the apparent reality has become quite the opposite of what it seems: the guests are speaking in a language he doesn’t understand, and the home town is suddenly not his either. The Olympic medallist begins to give a speech, to establish not just those facts but also that he is not actually even able to swim. He had always wanted to learn, but “never had the opportunity”.

It’s one of the fundamental factors of the Kafkaesque logic of simultaneity that he is the new Olympic world record holder in swimming, and at the same time he is not: “[…] I have broken the record, have returned to my country, and do indeed bear the name by which you know me. All this is true, but thereafter nothing is true. I am not in my fatherland, and I do not know or understand you.”

The text ends abruptly, in the middle of the speech by the “Great Swimmer”, as he is called at the beginning. For Kafka himself, swimming became a necessity in his life. Even shortly before his death he thought in wistful melancholy of those moments in the “Civilian Swimming School”. Like almost nothing else, that activity must have given him the opportunity to swim free in the most literal sense. When a doctor one day recommended that he should take a break from water sports after suffering heart problems, he wrote to Felice Bauer: “… not swim, that’s impossible”.