Martin Walser

A 20th-century literary luminary

Impulsive, stubborn and unforgiving – this was all part of Martin Walser’s character. He was a man of the 20th century and one of the greatest writers of his time.

The Nussdorf neighbourhood of Überlingen is one of the most beautiful spots on Lake Constance. Its streets are named after local freshwater fish, “Zum Felchen”, “Zur Äsche” or “Zum Zander”. If you turn off Nussdorfer Strasse and head for the lake along “Zur Forelle”, which leads into “Zum Hecht”, lakeside houses line the right-hand side of the road like a string of pearls. They’re not showy houses. The real wealth shows itself here in the casual self-confidence of the elegant middle class. On the left, the baroque monastery church of Birnau comes into view, on the right a wood-shingled house with a low fence, beyond it the lake.

This is where Martin Walser lived from 1968, and the combination of German post-war prosperity, lakeside charm and Catholic milieu so formative for Walser’s life and writing could not be more accurately captured in a picture than in this one. In his early, socialist years, incidentally, Walser – who had recently become a lakeside property owner himself – got into trouble with his neighbours when he demanded the entire shoreline be made accessible to the public.

Martin Walser was born in Wasserburg on Lake Constance in 1927. A childhood in his parents’ inn and therefore growing up under National Socialism find literary expression in one of his most important and finest ever books, the autobiographical novel Ein springender Brunnen (A Gushing Fountain), which was published in 1998. Not long after, he was accused (from a narrative perspective, abstrusely so) of having consistently left out Nazi extermination camps in the book. In this context, Walser made reference to his eternal adversary Marcel Reich-Ranicki’s “intention to condemn and offend” – the literary critic who himself had always referred to the author as a friend. Walser sought revenge in the early 2000s with his novel Tod eines Kritikers (Death of a Critic), prompting his departure from his literary home, the publishing company Suhrkamp.

Nothing is true without its opposite

Since childhood, a leitmotif running through all of Walser’s novels was that of rivalry. While as a boy it was the all-important question of which village inn had more guests – his parents’ or somebody else’s –, in his early novels, Martin Walser presented the young, up-and-coming Federal Republic as a biotope shaped by competitive struggles, fantasies of decline and fears, in which the petit bourgeois was historically both the main actor and victim; the controlling but simultaneously the self-exploiting class, which – to continue in the jargon of the times – was prevented from coming into its own. The emotional struggles of the ordinary people, of the Helmut Halms and the Gottlieb Zürns, defined Walser's work right up until the late 1980s.And just as late-night TV host Harald Schmidt could never have perfected his satire of the Swabian reactionary without being one himself, Martin Walser has always remained a citizen in the best sense of the word. In his Anselm Kristlein trilogy (its title a tribute to his younger brother Anselm Karl), the monumental breakthrough novel Halbzeit (1960) and the sequels Das Einhorn (The Unicorn) (1966) and Der Sturz (The Fall) (1973), Walser prototypically portrayed a character who is doomed to fail because he is unable to switch sides. Born in 1920, Kristlein’s professional career took him from sales rep and advertising copywriter to employee in a company sanatorium. Walser’s early novels describe the Federal Republic’s achievement-oriented society, but at the same time, the author was himself a product of this society. This is reflected in the frequency with which he wrote books, his prolific output even at an advanced age. Only those who produce are valid. Only those who write are alive. Angstblüte, the title of a 2006 novel, is also a reflection of Walser’s own productivity.

In 2012, an MP3 CD was published of radio recordings and interviews with Walser that were collected over a period of many decades. What is fascinating here is the specificity – but also the eloquence – with which the author struggles to find just the right words with conversation partners such as Peter Wapnewski, Herbert Heckmann or Heinz Ludwig Arnold. Listening to Martin Walser, to this darkly rolling Alemannic inflexion, coupled with rhetorical prowess and a never-ending eagerness to debate, was always a delight. The title of the radio interview CD, incidentally, was Nichts ist ohne sein Gegenteil wahr (Nothing is true without its opposite) – a programmatic Walser quote that also reflects the difficulties the public had with this writer (and vice versa), because his ambivalences were seen as opportunism and his radically subjective voice as universal. Not without Walser’s intervention. Interviews about social issues were readily accepted: “It’s about Germany, it’s your duty,” he told himself. When Suhrkamp editors rebelled against the publisher Siegfried Unseld in 1968, Martin Walser, of all people, was called in to mediate. The publishing company’s chronicles document how Walser succeeded, in just one sentence, in agreeing first with Unseld and then, in the second part of his convoluted hypotaxis, with the rebellious editors, thus duping both sides. Nothing is true without its opposite.

A talented stylist

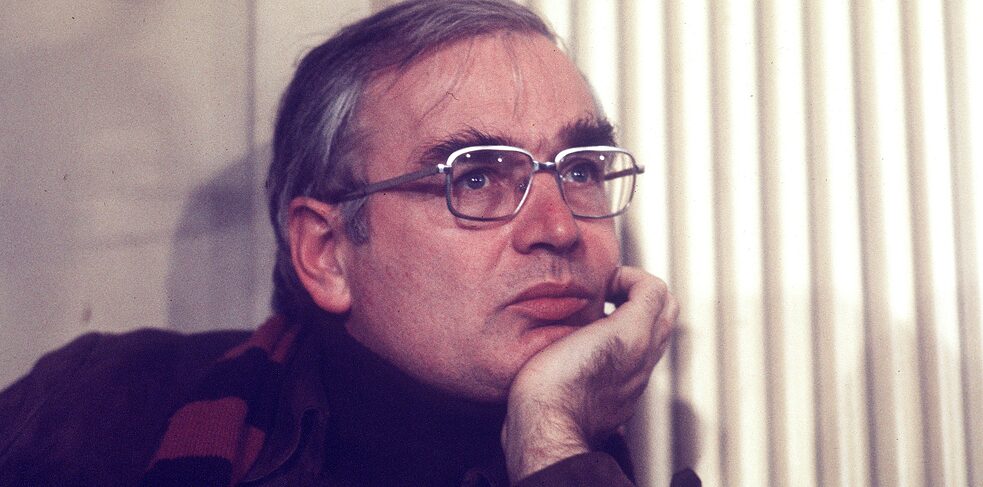

Writer Martin Walser in 1978 | @ picture alliance / Sven Simon

Writer Martin Walser in 1978 | @ picture alliance / Sven Simon

Walser’s novel Jenseits der Liebe (Beyond All Love) appeared in March 1976. Reich-Ranicki tore the book to shreds under the heading Beyond Literature. Walser was away on a reading tour and sitting in a train when he read the FAZ review. On 27 March 1976, Walser drafted a “speech to Mr R-R” in his diary, which read: “I can only reach the general audience before whom you have denigrated the motives of my ten-year-long journalistic endeavours if I take legal action against you or slap you in the face. Since I do not have the means to take legal action against you, I have no choice but to slap you. So I am telling you, if you come within my reach, I will slap your face. With the flat of my hand, by the way, because I will not make a fist for your sake.” It never came to that. Walser later delivered his face slap in the form of a novel.

Impetuous, stubborn, unforgiving – this was all part of Martin Walser’s character. Impulsive, eager to appear in public, standing up to deliver speeches even at an advanced age; inherently charismatic, belligerent. At the same time, Martin Walser always insisted on the pre-eminence of the subjective. In an interview, Walser said: “Now that there is no material apart myself, I am my own material with my struts, snarls and difficulties, and all these are important for my work.”

At the launch of his novel Muttersohn in the baroque monastery of Bad Schussenried in 2011, Walser maintained it was complete madness to hold an author responsible for what he writes. For Walser, his books as well as his speeches were also a form of self-defence, a counter-attack on an attack that no one but himself has perceived as such. It is a constant game of stimulus and reaction. This is also how Walser’s infamous Paulskirche speech from 1998 should be understood. Upon his acceptance of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, Walser spoke of Auschwitz becoming a “routine threat” and the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin as a “nightmare the size of a football field”. The audience stood up to applaud, but Ignatz Bubis, then chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, remained seated.

Büchner Prize, but never the Nobel Prize

Politically, Martin Walser was far more difficult to pin down than the buzzword-oriented public wanted to believe. He started out as a socialist. Political impulses always stemmed from a sense he was lacking something. The political left, however, resented his advocacy of German unity long before the Iron Curtain came down. Constraints of all kinds provoked the anarchist in Walser, especially linguistically. The Paulskirche speech can also be interpreted as an insistence on a privacy that was directed against public expectation. A self-enquiry, not a normative text. A deeply unfortunate appeal, as Walser acknowledged years later, against pre-agreed language regulations and metaphors. Walser had a feel for socio-political mechanisms. His 1996 roman à clef Finks Krieg garnered considerable public attention but received mixed reviews from the critics. If you read the novel again today, you discover first and foremost an immensely sharp portrait of Alexander Gauland. Gauland himself, incidentally, as one of the protagonists of the novel, reviewed the book in the FAZ.Martin Walser was an exceptionally talented stylist. An author who mastered the tirade, parlance, the flow of speech and its nuances like no one else. Equally, as his wonderful Messmer books show, he was an aphorist of the first order, witty and astute, later in life increasingly dark and morbid. He became briefer in his latter years, but also more insistent. It was as though he was still sending out strong, existential signals from his lakeside house. With his 2017 Statt etwas, oder Der letzte Rank, Walser entered a late phase in his creative life, his texts consisting of short sharp sparks, flashes, aphorisms. But they were beautiful and poignant, too. In Das Traumbuch oder Postkarten aus dem Schlaf, all of Walser’s themes appear once again – shame, including the physical kind, finding material, Reich-Ranicki.

Walser bade farewell to the world by writing: “After waking up, reality, a dull, moodless milieu.” There are countless stories about Martin Walser. The blow he dealt his conversation partner is legendary; a mixture of recognition, affection and a gentle reminder not to give in. In his experiences, aspirations and constraints, Martin Walser, who received the Büchner Prize in 1981 but not the Nobel Prize for Literature that he had deserved, was clearly a man of the 20th century. As such, however, he was also a literary luminary.

This article first appeared in ZEIT ONLINE.