Cultural reunification

The Return of German Graphic Novels

The reunification has put Germany back on the world map of graphic novels, after a new German avant-garde originated from a group of graphic artists from East Berlin. The comic-friendly climate at German Universities promoted the development of new directions and the spectrum of subjects and styles in German comics is widening. A look back at 30 years of German comic history.

The fact that Germany has been back on the world map of comics for many years is also due to reunification. And it was the East German part of the country that played the more important role in this return - at least if aesthetic aspects are given more weight than economic ones.

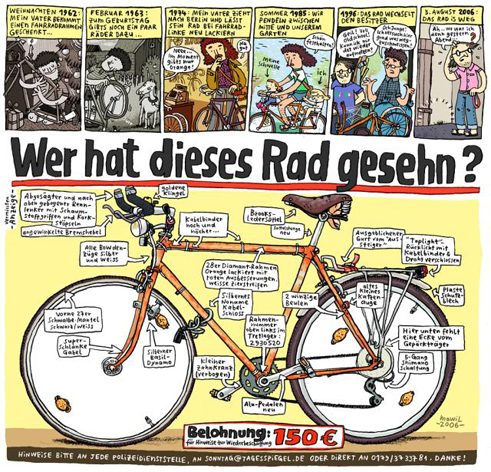

Mawil: Bycicle-Tour-Checklist, Der Tagesspiegel, Juli 2008

| © Der Tagesspiegel

There were of course some individual German comics artists who had made a name for themselves before 1990, but no matter whether one is talking about Matthias Schultheiss or Ralf König as artists whose work has achieved international acclaim, Walter Moers or Rötger Feldmann aka Brösel as examples of more local success stories, or Hannes Hegen and Rolf Kauka as leading figures from the 1950s and 60s – all of these artists adopted long-established stylistic conventions and narrative forms that were developed in other countries; among their main influences were the American satirical magazine Mad, which was launched in the 1950s, Walt Disney, the French comics scene and the American underground movement.

Mawil: Bycicle-Tour-Checklist, Der Tagesspiegel, Juli 2008

| © Der Tagesspiegel

There were of course some individual German comics artists who had made a name for themselves before 1990, but no matter whether one is talking about Matthias Schultheiss or Ralf König as artists whose work has achieved international acclaim, Walter Moers or Rötger Feldmann aka Brösel as examples of more local success stories, or Hannes Hegen and Rolf Kauka as leading figures from the 1950s and 60s – all of these artists adopted long-established stylistic conventions and narrative forms that were developed in other countries; among their main influences were the American satirical magazine Mad, which was launched in the 1950s, Walt Disney, the French comics scene and the American underground movement.

“PGH Glühende Zukunft”

While German picture stories had been created in the past by the likes of Wilhelm Busch and e. o. plauen, the alias of a certain Erich Ohser, who produced the cartoon series Vater und Sohn [Father and Son] from 1934 until 1937, it was only with the emergence of the comic avant-garde from 1990 onwards that the German comics scene could once more be termed independent.The nucleus of this avant-garde movement was Berlin, and if one had to select a single name, it would be that of a collective: PGH Glühende Zukunft (PGH Glowing Future) was the name chosen by a group of artists from East Berlin as an ironic reference to the Produktionsgenossenschaften des Handwerks (craft production cooperatives or PGH) that were characteristic institutions of the socialist era. PGH Glühende Zukunft was established directly following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and consisted of Anke Feuchtenberger, Holger Fickelscherer, Henning Wagenbreth and Detlef Beck.

They had all grown up in East Germany and received a solid education in the graphic arts, which involved learning techniques that had long been abandoned in the western art education. Working with hand presses, woodcut and linocut printmaking techniques, calligraphy and book design formed the foundation of the Berlin quartet’s art. Eben slightly younger artists such as Georg Barber aka Atak and Kat Menschik could still benefit from the traditional training provided in East Germany.

Curiosity about comics

These artists became known above all for their poster designs and cartoons, but this was merely a continuation of what was already possible in the GDR. There had, however, never been a platform for creative or artistic comics in East Germany, and comic production was limited to the monthly publication Mosaik and the occasional series in the party-controlled youth magazines Atze or Frösi. In the eyes of the GDR regime, comics (which were not even allowed to be called that) were only for children. The East German authorities thus completely failed to recognize the narrative potential of graphic novels.The members of PGH Glühende Zukunft were correspondingly keen to explore this narrative genre, and from then on they mainly produced graphic novels, even though this meant they could only make a living by taking on other graphic arts work. At the same time, however, not having to make an income from their comic strips allowed them to experiment in ways that established West German comics artists would not have dared, for fear of endangering their commercial success. The work of the four Berliners made conscious reference to Expressionism – the major modern art movement that is very closely associated with Germany.

Darkly humorous stories

Line Hoven: Liebe schaut weg, Reprodukt 2007

| © Reprodukt

And this traditional line of approach proved very popular abroad, because something was suddenly appearing in comics from Germany that people were already familiar with from art history as one of this country’s most significant accomplishments. Most of the comics created by the PGH artists were darkly humorous with existentialist or cynically satirical undertones, and seemed to hark back directly to the decade during which Berlin was the global capital of art: the 1920s during the Weimar Republic.

Line Hoven: Liebe schaut weg, Reprodukt 2007

| © Reprodukt

And this traditional line of approach proved very popular abroad, because something was suddenly appearing in comics from Germany that people were already familiar with from art history as one of this country’s most significant accomplishments. Most of the comics created by the PGH artists were darkly humorous with existentialist or cynically satirical undertones, and seemed to hark back directly to the decade during which Berlin was the global capital of art: the 1920s during the Weimar Republic.Anke Feuchtenberger, who was above all creating feminist comic strips based on literary material contributed by the author Katrin de Vries, and Henning Wagenbreth with his unmistakable pictogrammatic style became the figureheads of the German comic avant-garde in the mid-1990s – the former in France, the latter in America. Fickelscherer and Beck, on the other hand, did not manage to break into the international comics market. But two West German artists did achieve this around the same time: Hendrik Dorgathen and Martin tom Dieck.

Successful abroad

Dorgathen had already gained success as an illustrator before producing his wordless comic Space Dog; published by Rowohlt Verlag, one of West Germany’s most prestigious literary publishing houses, it quickly became an international sensation. The Hamburg-based artist Martin tom Dieck established his reputation with a comic strip written by Jens Balzer entitled Salut, Deleuze! (Hi, Deleuze!), in which the post-structuralist philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan became the thematic focus of a highly intelligent account of the four dead philosophers’ descent into hell. The comic was first published in 1998 in France, followed by a German edition released two years later by a Swiss publisher.This example remains characteristic to this day: many German artists – above all those who produce the most thematically ambitious work – enjoy greater success abroad, especially in France, than they do at home. Artists such as Ulf Keyenburg aka Ulf K., Barbara Yelin or Jens Harder have published a great deal more abroad than in Germany; this is no doubt also due to their choice of subject matter, which may be perceived to be typically German in an international context and for this reason be particularly popular in other countries.

Romanticism and modernism

The work of Ulf K., for example, with his two main characters Monsieur Mort and Hieronymus B., makes direct reference to German art history by featuring themes such as the Dance of Death or grotesques – the most impressive examples of which were produced in the early modern period by Hans Holbein the Younger and Hieronymus Bosch; at the same time it links back to the fantastical imagery in the art of Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901) or Max Klinger (1857–1920), whose paintings mark the point of transition from the Romantic period to a modernist movement that draws on dream motifs, Surrealist themes and pastiches of mythological subjects.Barbara Yelin, on the other hand, creates comics with structures and themes that owe a great deal to Romantic art, while Jens Harder’s two main projects to date, the large-scale comic books Leviathan and Alpha, can be related to the zoologist Ernst Haeckel’s (1834–1919) efforts to produce systematic graphic representations of nature. Following Darwin’s lead, Haeckel attempted to depict evolution in the form of elaborate schemata; above all, however, his illustrations caused a stir among artists and philosophers. It can therefore be seen that comics which can be directly or indirectly related to what are considered to be particularly German strands of art history meet with an overwhelmingly positive response in other countries. In January 2010, for example, Alpha was awarded the Prix de l’Audace (award for courage) at Europe’s most important comic festival held in the French city of Angoulême.

Comic-friendly climate

The current success of German graphic novels is due to a lot more than just avant-garde forms of narration, however. Since the older generation of artists have taken on teaching posts at art colleges – Feuchtenberger in Hamburg, Wagenbreth in Berlin, Dorgathen in Kassel, Martin tom Dieck in Essen, Atak in Halle – a comic-friendly climate that favours pictorial narration as a whole has finally been established at German universities. Some of the most successful German graphic novels of the last decade were originally created as academic theses, whereby Held (Hero) by Felix Görmann aka Flix and Wir können doch Freunde bleiben (We can still be friends) by Markus Witzel aka Mawil deserve special mention: the first is a fictitious West German autobiography, the second a real East German one.The spectrum of subjects and styles in German comics is also widening.Two centres of comic production have been established: one in Berlin, where the comic group Monogatari (the Japanese term for storytelling) has made a name for itself, and the other in Hamburg, where Anke Feuchtenberger’s courses at the Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften (University of Applied Sciences) have led to the formation of a closely-knit group of young graphic artists, who also benefit from the fact that three other established artists – Martin tom Dieck, Markus Huber and Isabel Kreitz – live in the same city.

Unknown narrative principle

Arne Bellstorf: Der Tagesspiegel-Comic Series

| © Der Tagesspiegel

With the annual publication of the graphic novel anthology Orang, Feuchtenberger’s former students Sascha Hommer and Arne Bellstorf have created a forum for these Hamburg-based artists, who are now all around thirty years old. The group also includes two female artists – Line Hovenand and Moki – who with their references to classical woodcut illustrations (Hoven’s scratchboard technique) and the manga aesthetic (Moki’s hand-drawn fantasy worlds) explore the two extremes between which young German comics artists are currently working.

Arne Bellstorf: Der Tagesspiegel-Comic Series

| © Der Tagesspiegel

With the annual publication of the graphic novel anthology Orang, Feuchtenberger’s former students Sascha Hommer and Arne Bellstorf have created a forum for these Hamburg-based artists, who are now all around thirty years old. The group also includes two female artists – Line Hovenand and Moki – who with their references to classical woodcut illustrations (Hoven’s scratchboard technique) and the manga aesthetic (Moki’s hand-drawn fantasy worlds) explore the two extremes between which young German comics artists are currently working.At Monogatari in Berlin, whose members include Jens Harder, Mawil, Ulli Lust, Tim Dinter, Kathi Käppel and Kai Pfeiffer, a trend towards documentary-style comics has developed that focuses not only on the highly successful model of autobiographical narration but also on phenomenological observation. The German-Israeli comic reportage project Cargo, in which Harder and Dinter were involved, provides a good example of this narrative principle, which was previously unknown in Germany but has subsequently also been employed by Ulli Lust and Kai Pfeiffer in their visual explorations of Berlin.

International success

Reinhard Kleist: Cash – I See A Darkness, Carlsen Verlag 2006

| © Carlsen

In the graphic biography of Johnny Cash by another Berlin-based artist, Reinhard Kleist, whose early work was inspired by the comic avant-garde of the 1990s, a further trend can be identified: the topical comic. Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness has achieved significant national and international success, as has Isabel Kreitz’s exhaustively researched historical comic about the spy Richard Sorge, who betrayed Hitler’s invasion plans to the Soviet Union while he was employed at the German embassy in Tokyo during the Second World War. Although her story is set in Japan, Kreitz chose not to incorporate stylistic elements typically found in Japanese manga (comics). Many German artists from the younger generation have however found inspiration in the Far East: as in many other countries, a whole new market segment has developed in Germany in response to the continuing rise of manga since the 1990s, and this has already produced a number of homegrown manga artists. Of particular note is the number of women who are active as mangaka (manga artists). These include Anika Hage, Christina Plaka, Judith Park, Nina Werner, Olga Rogalski and the creative duo Dorota Grabarczyk and Olga Andryenko, who publish their work under the pseudonym DuO.

Reinhard Kleist: Cash – I See A Darkness, Carlsen Verlag 2006

| © Carlsen

In the graphic biography of Johnny Cash by another Berlin-based artist, Reinhard Kleist, whose early work was inspired by the comic avant-garde of the 1990s, a further trend can be identified: the topical comic. Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness has achieved significant national and international success, as has Isabel Kreitz’s exhaustively researched historical comic about the spy Richard Sorge, who betrayed Hitler’s invasion plans to the Soviet Union while he was employed at the German embassy in Tokyo during the Second World War. Although her story is set in Japan, Kreitz chose not to incorporate stylistic elements typically found in Japanese manga (comics). Many German artists from the younger generation have however found inspiration in the Far East: as in many other countries, a whole new market segment has developed in Germany in response to the continuing rise of manga since the 1990s, and this has already produced a number of homegrown manga artists. Of particular note is the number of women who are active as mangaka (manga artists). These include Anika Hage, Christina Plaka, Judith Park, Nina Werner, Olga Rogalski and the creative duo Dorota Grabarczyk and Olga Andryenko, who publish their work under the pseudonym DuO.

distinctive narratives and styles

What they all have in common is the fact that, unlike the previously mentioned artists, they have had no formal artistic training, but instead started out as fan artists and worked their way up via talent competitions. For this reason, categorization into schools or according to historical traditions plays a much less significant role for mangaka than for other comics artists. The more open structures of this scene have brought a lot of new energy into the realm of German comics, particularly in the commercial/popular sector, and the global success of the manga aesthetic also ensures that the young artists achieve recognition beyond national borders.When a comic artist also makes clever allusion to German history, as Christina Plaka does with the title of her successful series Prussian Blue (a reference to the synthetic colour that was invented in Germany and became famous in Japan thanks to Katsushika Hokusai’s series of woodblock prints Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji) or to the subject of football, as Anika Hage does in Gothic Sports, this too awakens the cultural curiosity of non-German readers. In this way, even in the form of a manga, the German comic proves itself above all by seeking and finding its own distinctive narratives and characteristic styles.

Comments

Comment