DEFA Film Heritage

“Did they really allow things like that?”

The films of the GDR’s state film production company, DEFA, always bore the stigma of being permeated by propaganda. That, however, is only part of the truth. When it comes to feature and animation films, fairy tales and documentaries there is a valuable artistic film legacy to be found. The DEFA Foundation wants to make them more easily available digitally.

By Judith Reker

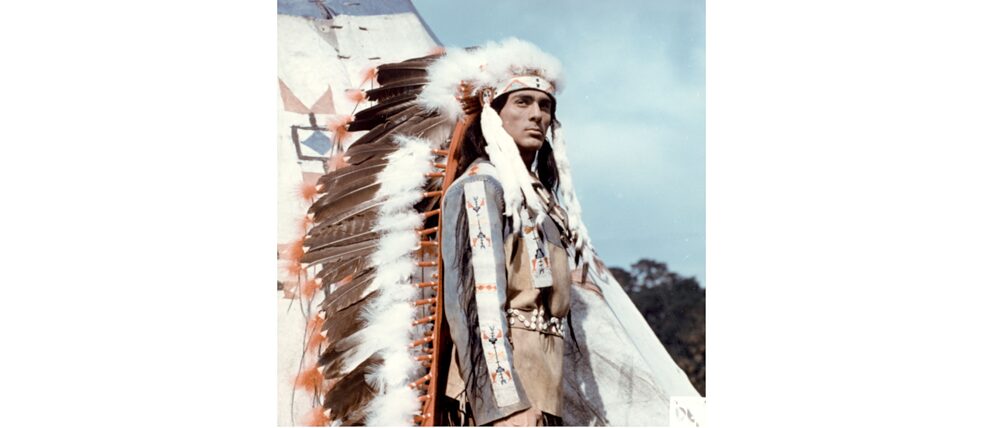

Around 700 feature films, including 150 children’s films, 750 animated films as well as 2,250 documentaries and short films, were produced by the GDR state film company DEFA (Deutsche Film AG) over a period of almost five decades. Its fairy tale films have become cult for generations, but there were also literary adaptations, anti-fascist films and politicised Westerns among its productions. The DEFA Foundation is the guardian of this film collection. This is a conversation with its chairperson, Stefanie Eckert, about the relevance of the GDR’s film heritage and new distribution channels.

Media scientist Stefanie Eckert has been working for the DEFA Foundation since 2001 and has been its chairperson since July 2020.

| Photo: © DEFA-Stiftung/Xavier Bonnin

Ms. Eckert, it has been 30 years since reunification. Why is there a foundation that only devotes itself to GDR films?

Media scientist Stefanie Eckert has been working for the DEFA Foundation since 2001 and has been its chairperson since July 2020.

| Photo: © DEFA-Stiftung/Xavier Bonnin

Ms. Eckert, it has been 30 years since reunification. Why is there a foundation that only devotes itself to GDR films?

This can be explained by history – after the end of the GDR, there was a need for an institution to which the rights to DEFA’s films could be transferred. As early as the spring of 1990, numerous DEFA filmmakers were already calling for the establishment of a foundation that would safeguard their cinematic oeuvre and prevent the film collection from being broken up in favour of private film rights dealers. Since it was established in 1998, the DEFA Foundation has held the rights to all DEFA cinema productions – around 13,500 films from five decades, including in-house productions as well as many foreign films dubbed into German and other material. The DEFA Foundation owns the rights, but not the material – this has been transferred to the German Federal Archives, which are also responsible for its preservation.

Do the East German films have a specific audience?

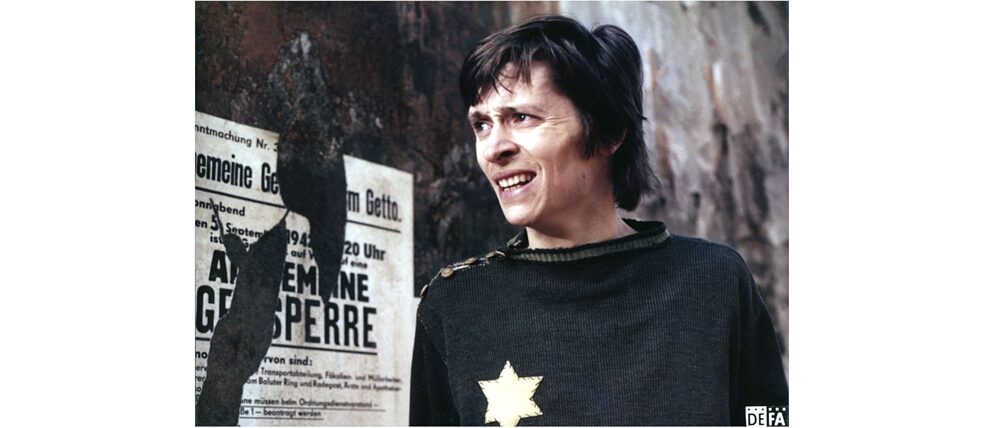

There are of course people who grew up watching DEFA films. They also write to us, wanting to see certain films or stars on television. Tens of thousands of DVDs are currently sold each year, primarily with children’s and fairy tale films, and the vast majority of these are distributed in East Germany. Then there are films that are popular all over Germany and also in an international context. Jakob der Lügner (Jacob the Liar) by Frank Beyer is a well-known example. The USA is also an important target group. There is a DEFA Film Library in America, which works closely with the Goethe-Institut and distributes DEFA films to academic circles in the United States.

What about the younger generation in Germany?

They cannot be reached via television, and this generation does not buy DVDs either. That is why our top priority is to get into the online market, that is, to be represented on as many streaming platforms as possible. In the meantime, our official channel “DEFA-Filmwelt”, operated by our distribution partner ICESTORM, is now available on YouTube.

Are young people at all interested in GDR films?

Of course, to grab them, you have to make the films known. On the one hand, this can be done via social media. Another focus that is important to me is to integrate the DEFA film more into academic discourse. The films can be used in very different fields of study in order to analyse certain aspects of life in the GDR, such as film aesthetics or fashion. The DEFA film could also be examined as part of European cinematic history, because the DEFA filmmakers, like the West German filmmakers, always compared themselves with their West and East European neighbours. Cinematic movements such as the New Wave in Poland or the Nouvelle Vague in France were also reflected in the film language of East and West German filmmakers.

In order to get onto the online market, the films have to be digitised. Given the large number of films, how do you decide in which order this happens?

When it comes to digitisation, we try to strike a balance, for example, between the different genres and between commercial necessity and curatorial interest. When a request comes from a television company, a film is, of course, digitised immediately, because it is clear – we are going to gain an audience with it. By the way, digitisation is a very intensive, detailed and, therefore, expensive job that takes several weeks, sometimes several months, per film. Our aim is for a digitised film to have the same quality as the premiere copy. We try to achieve this through careful colour correction and careful retouching, if possible in cooperation with the respective filmmakers and cameramen.

Do you actually experience a West German prejudice against GDR films?

No, we are not confronted with such prejudices in our everyday work.

Back in 2008 the filmmaker, Volker Schlöndorff, publicly voiced criticism. He said, among other things, “The DEFA films were terrible.” He later withdrew that. You were already at the DEFA Foundation back then, what was the reaction?

We were horrified and it left an uncomfortable feeling, especially so many years after the fall of the Wall. I think the discussions about the East German identity and the feeling of not being taken seriously also stem from such, perhaps carelessly made, statements.

Is it a prejudice or a fact that GDR films were propaganda films?

Generally speaking, it is a prejudice. Yes, the DEFA was part of the state apparatus; it was a VEB, a state-owned company. The main film administration, which was based in the Ministry of Culture, had to accept every film that was shown. It is therefore understandable that such prejudices arise, that all DEFA films are propaganda films or at least politically one-sided films. That, however, is actually not the case. In almost five decades of DEFA, there were phases that were much more restrictive, and there were phases when films were produced that would make today’s audiences think: Wow, did they really allow things like that?

Germany will commemorate its reunification 30 years ago on October 3, 2020. Do you have any film recommendations?

Unsere Kinder (Our Children), a documentary by Roland Steiner. The filmmaker portrays the various youth movements in East Berlin from the late 1980s, from Goths to neo-Nazis. The film says a lot about the GDR at that time and maybe also about what happened in the East German federal states afterwards. In any case, it is one of many films worth seeing from the legacy of films left to us from the former East Germany.