Artificial Intelligence

The machine that unleashes our creativity

British mathematician Marcus du Sautoy is convinced that artificial intelligence (AI) can be as creative as humans and might even attain a state of consciousness in future: a discussion on the current creative limitations of AI, its ability to surprise us, and how AI changes the way our species is looking at its own creativity.

By Harald Willenbrock

Marcus du Sautoy, a general question to start with: What is creativity – and who is creative?

Creativity is a word that is hard to pin down, just like consciousness, which is interesting as the two are closely linked. My hypothesis is that as a species, our creativity emerged about the same time as our consciousness because, as psychologist Carl Rogers put it, creativity became our tool for exploring this strange inner world. With regards to creativity, I quite like cognitive scientist Margaret Boden’s definition as something that is a) new b) surprising and c) has value. Creativity means novelty, because if you create something, it has not been there before. But novelty alone is not enough, it also needs to move us and to make us look at things in a new way. And value is an important factor because you don’t want your creation to just be surprising, but also to resonate and change things.

As you say that creativity and consciousness emerged together – when and how did that happen?

The human species started making tools for hunting or cutting things around 200,000 years ago, but I wouldn’t call that creative. Creativity began when we began making things that did not necessarily have utility. The first paintings appeared around 40,000 years ago. I guess that was quite a crucial moment when a voice probably appeared in our heads and started asking questions. When you’re wasting time and the tribe allows a tribe member to spend days modelling a figure out of a bone – then you are starting to see creativity and it has to do with our consciousness.

But the first person who took a stick or stone to kill a mammoth instead of wrestling it down was creative as well, right? The method was new, had value and was surprising – at least for the mammoth.

No, I think it lacks surprise and it’s certainly lower in involving you emotionally. But this is a very interesting point for me as a mathematician because I am constantly wrestling with the distinction between two words: creation and discovery. We mathematicians often talk about the creativity of our subject, and there’s definitely creativity involved. But once you create something, people say it has always been there waiting to be discovered. But you have to keep in mind that discovering something requires the act of imagining that there is something to be discovered and brought to life.

Which is a good segue to AI: In 2019, you published a book called “The Creativity Code: How AI is Learning to Write, Paint and Think”. What fascinated you so much about AI and its link to creativity that you wrote an entire book about it?

Mathematics is traditionally regarded as something a computer might be able to do. So when IBM’s Deep Blue chess computer beat chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1996, it was an existential crisis moment for us. As a logical sport, chess was seen as something quite like mathematics. But mathematics involves a lot more intuition, pattern-searching and somehow unarticulated moves, so we always assessed the game of Go as something much closer to mathematics than chess. Then when I saw machines playing Go at an incredibly high level, I realized that this was a phase-change moment that would have an impact on me in my own creative world. That was the spark. My book is very much the result of a personal exploration.

You are referring to the March 2016 match between the AlphaGo AI program and Lee Sedol, then the best human Go-player in the world, where the machine made a rather unexpected move. Would you call that move a sign of creativity?

It was not big news that a computer beat a human being at the game – we have become quite used to computers that can do things better than us. They do mathematical calculations faster than we do, they are more successful than us at chess, and at some point they will drive a car safer than we can. The shocking thing was a specific move in game two, since it so clearly passed the three tests that I set for creativity. Firstly and secondly, it was new and it surprised the judges. There are YouTube videos showing this wonderful moment when all the commentators literally said “Oh, that’s a surprising move.” None could understand why AlphaGo made this incredibly weak move that early in the game. And ultimately, AlphaGo even showed how you could use the move to create value, meaning to win the game. Which it did.

What were we actually seeing in that moment: the creativity of the code – or that of the coder?

Well, if you’d seen that line of code as a human Go player, you would definitely have deleted it, saying “Oh, that’s not a good strategy.” That’s the crucial point. All the learning processes AlphaGo went through made it put in a line of code that no human ever would have added.

When AI beats human intellect: Scene during the match between chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue chess computer.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Stan_Honda

We humans regard ourselves as the only creative species on this planet – what does it mean for us to possibly have a serious competitor?

When AI beats human intellect: Scene during the match between chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue chess computer.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance/dpa/Stan_Honda

We humans regard ourselves as the only creative species on this planet – what does it mean for us to possibly have a serious competitor?

With regards to our self-awareness, it’s a slightly Copernican moment. For centuries science has been shifting us away from the centre and away from the top, and our last bastion is consciousness. There might come a day when something is more aware and conscious than we are. But today I see AI more as a tool we can use to explore our own consciousness. If you keep in mind how routinely we often think and behave, machines might ultimately help us as humans to behave less like machines.

What can AI do what we’re not able to – and how can this move us forward?

You have to keep in mind that an AI engages with a dataset on a scale that we can’t. It can, for example, read all of Victorian literature in one afternoon, while I can barely read a few of those novels in a year. And I suspect that there are books that haven’t been read for a hundred years but deserve to be read so we might understand things from our past better. AI brings scale into the game, and that’s a big difference. It is a bit like the telescope given to Galileo: It allows us to see deeper and further than our human embodiment can allow.

Apart from these opportunities, do you see AI as a threat as well?

There is, of course, the idea that this might be the time of our last creative acts, as these algorithms might wipe us out one day. But that’s just a good Hollywood narrative in my view. And certainly, jobs will go, such as those creating music for corporate videos or programming simple computer games. AI can do the work very quickly. So it will pose a threat for some creative industries. But for now I see AI as more of a tool that we shouldn’t give too much identity yet. There are certainly areas where AI is successful and others where it’s not doing terribly well.

Why is that?

In the visual world, we’ve seen breakthroughs in AI recognizing things in an image and therefore also being able to create very interesting visual images. But at this point, AI still has problems in any area with a temporal element. You can listen to an AI jazz improviser for 30 to 60 seconds, but it gets really boring beyond that because it doesn’t know where it is going. it is the same with the written word: AI does well for around 350 words, but sort of loses the plot after that. One of the shortfalls is that when we show AI how to write a book, we only show it the written word. If we teach it music, we show it music. But when we humans create, we have a huge dataset we can tap into, comprising visual, oral and written data.

Can you give an example of that difference between human and AI creativity?

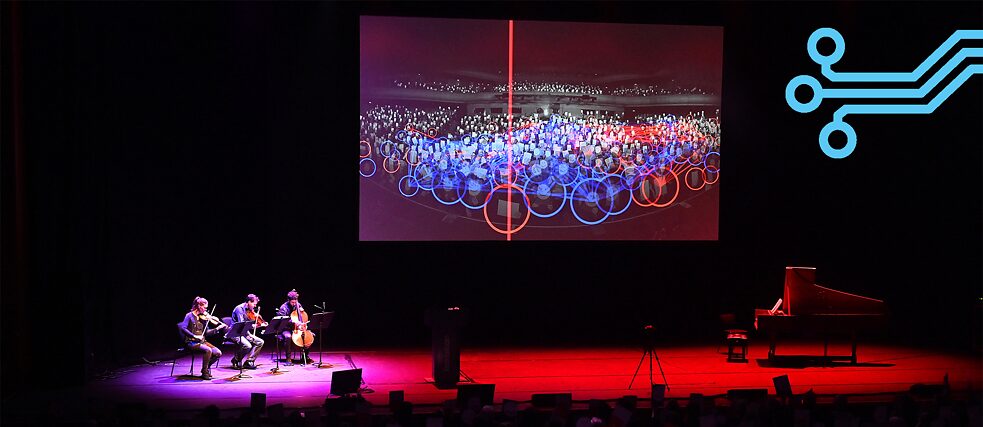

I did an exercise at the Barbican Performing Arts Centre in London about Bach, where we got an AI to learn from all of Bach’s keyboard works except his English Suites. We then took parts out of the English suites, instructed the AI to fill in the gaps, then asked the audience if it could see the moments when it went from Bach to AI and back again. While it was quite hard for the audience to detect, the harpsichord player said he could say exactly when it switched to AI. First of all, he said, the AI parts were too hard to play. The AI was unembodied, whereas Bach had written things that were nice for his fingers. Secondly, he explained, it was called the English Suites, because Bach loved the cadences of the English language when spoken and tried to capture them for the keyboard. So Bach had an extra dataset: the English language. Here we see one of AI’s limitations: It relies on very narrow datasets. That also explains why it falls down with languages and something called Winograd challenges – sentences often used in Turing tests to sniff out who’s the AI and who’s the human. Here’s an example: “The government banned the protesters from marching because they feared violence.” We humans know instinctively that the “they” refers to the government, and we know that from a huge historical context, whereas the AI has no idea at all.

With AI evolving so quickly, isn’t it just a question of time until it catches up?

We have to remember that the human brain has gone through millions of years of evolution. Can we fast-track that with our knowledge of how the brain works? Well, even though we know about neurons and synapses and the actual architecture of the brain, it still may not be enough to fast-track consciousness. AI might need to go through the many iterations we had to go through, although at a higher speed. But that still might take decades.

When writing your book on AI’s creativity, you had an AI helping you. How satisfying were the results?

I asked the AI to tell one of the stories I wanted to tell in the book – a story where I knew there was a lot of data available on the internet. It came up with something that was slightly bizarre, but pretty coherent, so I included it in the book. But I was a bit disappointed as I could quite easily identify the sources from where it had derived the thing it had created. Anyway, I didn’t tell anybody where the passage was – my editor still doesn’t know which one it is. Of course I find that deeply depressing. What does it say about me as an author? (laughing)

Did you then pass some of your royalties on to the AI? Or who do you think should get the credit and royalties if AI creates something – the coder, the company that assigned the coder to create the program, or the code itself?

Do you credit the parents of Picasso for his paintings? Or the painters whose work he studied? Not really. But the dataset that a code learns on is extremely important, so whoever has contributed to that dataset is definitely part of its creations. I think AI’s involvement in creative processes will push us away from this obsession with the idea that we have a single creative genius behind everything. I like Brian Eno’s idea of a “scenius” rather than genius and that we have to credit many more people in the creative act than just the one.

If we met again 10 years from now, what will have changed in AI by then?

One of the exciting things about AI is the bespoke experience that it’ll allow us to have. Knowing your scientific background and what you’ve read, AI might understand you well enough to co-write a book that is bespoke for you. I think that’s certainly a possibility for 2030.

And if we look ahead to mid-century?

Well, we seem to have created something that could become conscious. Consciousness is nothing magical, it really comes down to a mix of math, physics, chemistry and biology that produces something which has an awareness of itself. I think we might ultimately be able to create this mix in a machine. And then the creativity of the machine is going to be the key element helping us to understand when that has happened. It won’t be gradual, it will be a flip, quite like water going from liquid to steam.