Fake News

“We cannot simply ignore disinformation”

What can we do about the flood of false reports, lies and conspiracy theories that that make the rounds on the internet every day? Many established media channels have begun countering fake news with fact checks, setting up departments to dig down on the truthfulness of reports and politicians’ statements. Public broadcaster ARD has taken this route and launched its fact finder team in 2017. Journalist and head of ARD fact finders Patrick Gensing talks about fake news and social media, and the challenge they pose for established media in Germany.

By Petra Schönhöfer

Patrick Gensing is head of broadcaster at ARD’s fact finder team.

| Photo: © WDR

Patrick Gensing, as editor in chief of the ARD fact finder team, you have been refuting false reports full-time since 2017. Is your team busier in 2021 than it was four years ago?

Patrick Gensing is head of broadcaster at ARD’s fact finder team.

| Photo: © WDR

Patrick Gensing, as editor in chief of the ARD fact finder team, you have been refuting false reports full-time since 2017. Is your team busier in 2021 than it was four years ago?

We always have a lot to do and, if we could deal with everything, we would carry out a huge number of fact checks every day. You’re right though: Thanks to the Corona pandemic, we are experiencing a new dimension of disinformation.

How do you choose your topics from the glut of fake news?

We base our choices on importance and relevance. Colleagues out reporting write to us and draw our attention to certain issues. Sometimes our colleagues from the social media department let us know about something that caught their eye in the comments. Then we select the topics we take a closer look at based on relevance.

How do you determine relevance?

Reach is one aspect we consider using a tool that allows us to see how often posts have been shared on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and so on. We also monitor what relevant people are saying. If people affected by disinformation are being systematically attacked, then that is an issue we’ll tackle too. And if certain narratives are repeated, we try to explain these patterns.

As you noted, social media play an important role in the spreading of fake news and often give an issue or debate very short shrift.

We have seen extreme acceleration in the rate of news consumption. Today, many people are bombarded with news on their mobiles 24 hours a day, seven days a week. They often choose to consume only the bits that fit into their own worldview so they don’t have to deal with contradictions, which in turn results in the famous echo chamber or filter bubble. If you want to acquire a differentiated picture of reality, you have to consume a variety of sources. But that is pretty hard work and news consumers need to be media literate to even understand how this would work. Combatting false reports is not just down to the media or politicians. There needs to be a real sense of civil responsibility in the digital world. People need to understand that they shouldn’t just pass on every random tidbit they picked up somewhere. The same is true in real life – if a perfect stranger tells me some nonsense on the street, I don’t just pass it on as it is. I start by considering who the person is, what he or she has told me, and assess how credible and plausible I feel the information is. You have to ask yourself these same questions when consuming media as well.

What options do the quality media still have for presenting reality in all its complexity and contradictions?

Fact checks are one of many ways to make the discussion more objective. It can also be helpful to take a step back and ask: What are we actually talking about right now? We need to explore certain terms and narratives and point out the mechanisms behind disinformation and targeted false reports so that people recognise them when they see them again with other topics. All conspiracy theories work according to the same principle, and this principle can be explained.

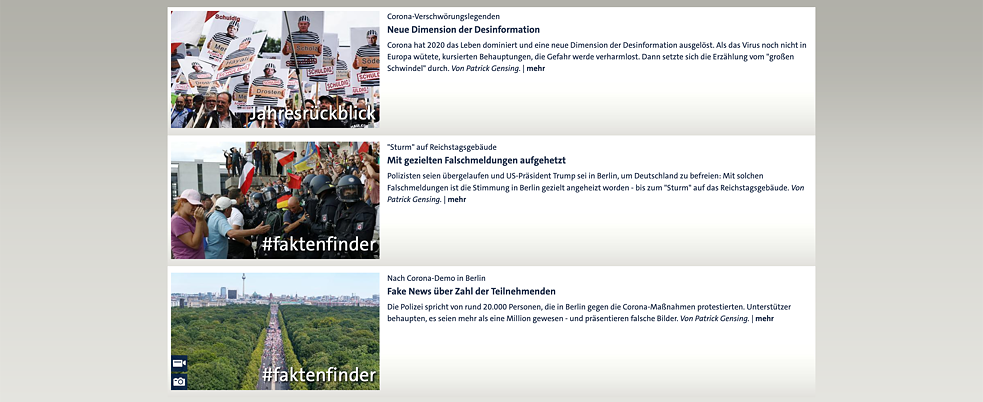

Screenshot of the ARD fact finder website.

| Photo: © Screenshot ARD faktenfinder

Is this situation perhaps also an opportunity for quality journalism?

Screenshot of the ARD fact finder website.

| Photo: © Screenshot ARD faktenfinder

Is this situation perhaps also an opportunity for quality journalism?

Yes, we’ve seen that effect as well. Media professionals have to reflect more critically on their role or redefine their role. Digitisation has also removed their gatekeeper function to a certain extent, as anyone can produce and disseminate news today. In one sense, this can be seen as a positive – the democratisation of discourse. When politicians consciously lie – and Donald Trump is the best example here – as media professionals we can’t just parrot back: “Donald Trump said such and such.” We need to add a professional assessment and indicate that what he said was not true. This is clearly a great opportunity for journalism. On the user side, the consumer side, we have seen users flocking to established media in times of crisis. This has happened with Germanys nightly news, the Tagesschau, during the Corona pandemic. We are seeing this same trend in the US, where traditional media like the New York Times are really booming. This gives us the opportunity to provide guidance when people read something on the internet and look to us to find out if it is true. In the jumble of digital streams, in the rushing flow of news, we can be the touchstones that people hold fast to.

Would you also like to see politics take responsibility for the spread of disinformation?

I am very cautious about legal intervention. There are already clear guidelines about the limits of freedom of expression, about criminal offenses such as defamation, slander and incitement to hatred. I don’t think we need any more laws. We do have to deal with the question of platforms: What responsibility does Facebook, for example, have for the content on its site? Facebook tries to argue that it is just a service provider. But if media law held them accountable for the content disseminated there, much less would happen. The fact that public discourse takes place on private platforms where the regulations are not transparent or easy to understand is a fundamental problem. It’s also a fundamental problem that the algorithms prioritise content that provokes as many reactions as possible and polarises people. If I’m interested in any one right-wing extremist site, I’ll immediately get lots of new suggestions, and in no time at all I’ll find myself in a parallel world. This, of course, contributes to the fragmentation of society.

Your work has repeatedly made you a target of personal attacks. How do you assess the security situation for journalists in Germany in general?

It has clearly intensified. For one thing, we’ve been subject to threats and insults for years, and I have been regularly targeted too. Now there is also the danger that colleagues on the ground will actually be physically attacked. Fanatical movements gain traction by portraying the media up as the enemy, as we are seeing with coronavirus deniers. Dozens of reporters were attacked in Leipzig and there were also attacks in Berlin. Clearly some people won’t stop at insults. Authoritarian leaders like Viktor Orbán and Vladimir Putin see free media as a threat because it cannot be controlled. That’s why they try to intimidate or silence them. And that is exactly what we cannot allow to happen.