Artificial Intelligence (AI) and artistic creation

Fantasising about the loss of control

“Can art be artificial and intelligent at the same time?”, is a question that unfolds a paradox: the hypothetical (according to some) or potential (according to others) intelligence of the non-living. Intelligence, the way we currently understand it, is a faculty of the biological life whose mechanism remains partially elusive to us.

By Nathalie Bachand

It gathers under the same hat the rational as well as the emotional – logic and creativity, anticipation and understanding of the past, along with self-consciousness. The human intelligence forms a complex whole that cannot be reduced to the development of algorithmic equations, at least not for the moment. Whether it is viewed as hypothetical or potential, the intelligence of the non-living is being questioned, and it is the subject of ongoing research. The non-living is essentially the unanimated such as materials, objects, things that have been built and destroyed – code? As a purely informatic product, the information that code represents is in perpetual transit from a point A to a point B to a point C or Z. And while you cannot say that it is alive, it is also not completely inert in the sense of any given material. It is an object of communication, artificial, without intrinsic evolutionary potential. However, we know today that it is possible to “nourish” code in order to make it autonomous, to cross it with computational neurobiology and mathematical logic to program machines that will imitate living beings. With code, you can program code to liberate it from its own program. Is this digital Golem really that intelligent?

Transfer of control

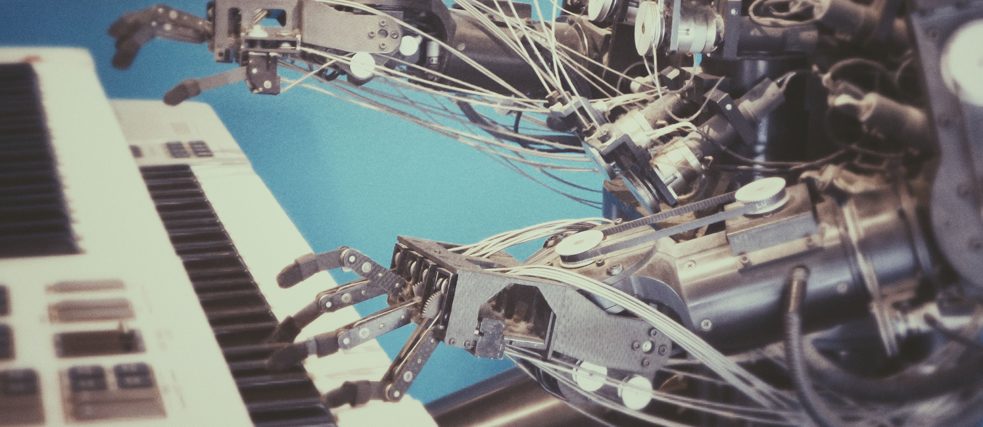

Art, which is mostly artificial, is generally meant to be seized by intelligent beings external to itself. We are shown a more or less complex “object” that we contemplate from different angles; we take into consideration its components, and we view the whole as an accomplished total. Some works, however, present themselves under more fluid forms, less obvious to grasp, rather elusive and unpredictable. Through the Haze Of A Machine’s Mind We May Glimpse Our Collective Imaginations (Blade Runner) (2017) by the Vancouver-based Canadian artist Ben Bogart is the result of a rearrangement of pixels and audio of the original version of the motion picture Blade Runner. Reorganised through the filter of a self-organising map, Blade Runner slips away from us just like the process that evolves in front of our eyes: the machine “works” based on spectral and chromatic similarities, thus starting from a relative logic, but it improvises in a way that diverts the expectations while constantly renewing the visual suggestion that emerges from it. Looking at the work is seeing what the acting gaze of the machine is seeing. Yet this gaze is a blind gaze, without intention. The film track, which is therefore bare of any narrative logic, offers the spectator a counter-intuitive cinematic experience. The data that constitute the work escape our comprehension and seem to respond to the requirements of an intelligence of a different kind. But in order to do this, the artist has had to “authorise” this transfer of control.One could argue that machine intelligence cannot be grasped with our usual criteria, but the machine is not at the source of this: we initially were the ones who wanted it. For the machine to produce haphazardly – and therefore something that we think belongs to it – it was necessary that someone wanted it, and that this person was capable of conceiving it. And, finally, it was necessary to program and authorise this computer program. This transfer of control - Dada, Situationists or William S. Burroughs can testify to this: the origins of computer-based art are analog processes such as the Cut-Up, the psychogeographical approach of the dérives and other recombination methods. Since the early 2000s a whole body of works have been created, often living on the Internet, whose material – generally text-based – emanates from the machine, unrecognizable and transfigured. EveryLetterCyborg V1.2 (2017-2018), a work by the Chinese-born and Toronto-based artist Xuan Ye, is exemplary of this type of work. It is an interactive installation and a TwitterBot at the same time, starting from an existing text to create a new, totally deconstructed text. In this case, the text source, A Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway (1984), is being “rewritten” with the help of an informatic algorithm, which in turn is based on a non-intentional composition method that was used by the poet Jackson Mac Low in the 1960. Each letter in the manifesto becomes the beginning of a new word that is randomly picked from a database of an online dictionary whose order does not conform with standard syntax. Each letter also becomes a cyborg, an informatic micro-Golem where the original literary work experiences its numerical hybridization in real time, both in reality and on Twitter.

The material is never innocent

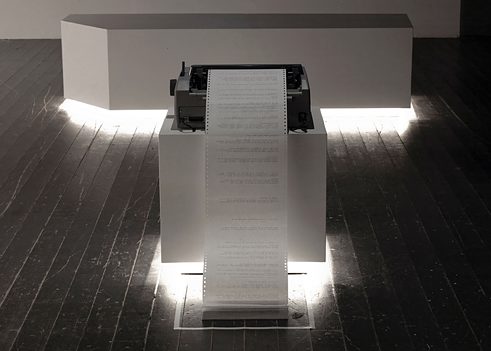

Similarly, the installation This Is Major Tom To Ground Control (2012) by Véronique Béland, an artist from Quebec currently living in France, uses an automatic random text generator. It is activated through the reception and analysis of radio waves sent by the radio telescopes of the Paris Observatory. The resulting text, which varies in its cohesion, is recited in real time by a synthetic voice. This continuously captured “message from the universe” is also being printed daily “in order to create an infinite library archive of messages coming from the cosmos” The question to ask oneself is maybe not so much who has created the work but rather what has created it. In the creation of a work of art, the material is never innocent – it always informs the artist about its potential, the direction in which it could go, and the character it allows it to take on. If algorithms and data can slip away from our control with our permission, they still do not escape this demand of the material in the creative process. Now does this not make the material a co-creator of the work?All We'd Ever Need Is One Another (2018) by Adam Basanta, a Vancouver native who lives in Montreal, pushes the idea of the machine as a co-creator of art a little further. The installation presents itself as an autonomous system that produces art, infinitely and at a regular rhythm. The work consists of a chain of auto-generated images without any intervention of the artist other than orchestrating it all. First two scanners pointing at one another scan each other at regular intervals following a computer script, producing an abstract image that mirrors the light conditions in the room where they are located. The image is then “analysed by a series of deep-learning algorithms trained on a database of contemporary artworks in economic and institutional circulation. When an image matches an existing artwork beyond an 83% match, it is ‘validated as art’ and uploaded to a dedicated website, Twitter, and Instagram account.” Certain high-ranking matches are printed live at the gallery and then “exhibited”. This being said, what is first and foremost exhibited is the entire process, the computer doing the scanning, evaluating the matches and concluding whether the result is worthy to be called “art”, or whether it is discarded into the limbus of the digital world, exactly where it came from. As the artist says himself, the entire process is “stupid” – without intention, it executes its program. In a way, we are just one leap away from Taylorism where the artist directs his assistants to execute the works of art. What is the difference between the studio of an artist like Olafur Eliasson or Takashi Murakami, and an automated production chain other that the fact that the assistants are replaced by computer scripts and programs?

Feed machines with humans

This October, Christie’s will auction off its first AI work, a piece by the Parisian collective Obvious entitled Portrait of Edmond Belamy (2018). The work, which has the appearance of a watercolour painting from the last century, is estimated to be worth between 7,000 and 10,000 Euros. Besides the question of its monetary value, and the fact that it “mimics” traditional art meanwhile its future owner will not be able to see any traces of code in it, it is worth emphasising that the work is signed with the mathematical equation of the algorithm that was used to generate the image, and not signed with the name of the collective. Thus, the artist allows AI to become the creator, or co-creator, of the work. This gesture though remains symbolic, as the “human” artist legally remains the originator – at least for the moment.Void of its own will and beyond any intention, we have seen machines generate content that “speaks to us”. And to speak to oneself in an even more convincing way, it is also possible to feed machines with humans. The series Ossuaires (2018) by the Franco-Canadian artist Grégory Chatonsky is a type of hybrid between a cyborg and a cannibal. The series was produced with several hundreds of 3D files of human and non-human bones which were then fed into a network of artificial neurons, a process by which the computer “learns” to create new bones. The result, a Cronenbergian testimony of a reality and its obscure double: the imagination of the machine, hesitating between recognition and difference, ends up producing something familiar, a similar estrangement. The unheimlich of this imaginary is that of the human unconscious extended through the computer code. The passage from one world to the other via Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs are a class of artificial intelligence algorithms used in unsupervised machine learning) or other automatic learning algorithms – from analog to numeric, and then back to analog – leaves its traces. Just like nighttime dreams that send us into the morning with unpredictable images, AI that “dreams up” art does not necessarily have to be intelligent in order to cross over into our imagination and transform our views. All you have to do is allow the program, and do not close your eyes when the unthought happens.

Comments

Comment