Restitution Debate Surrounding the Benin Bronzes

The Wish to Return Objects, Forbidden by Law

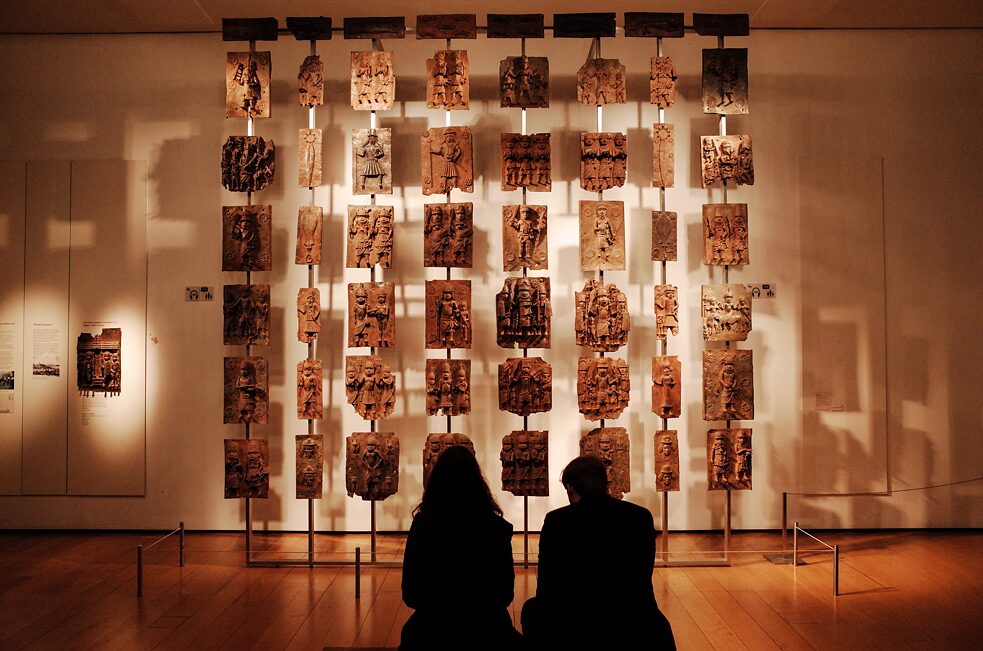

Benin Bronzes are exhibited in museums around the world, but the largest collection can be found in the British Museum. While Germany announced the return of the bronzes in its possession, some national institutions in England cite legislation as a reason for their inability to do the same. How much does the government impact British museums’ ability to return the objects?

On the very day that the German government announced it would start to return the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2022, I spoke to a contact at the British Museum. The German decision, this person agreed, was “very significant, on a gigantic scale”. For if, as Germany’s culture minister Monika Grütters said, her country was acting out of a sense of “moral responsibility”, where did that leave the British? It was British troops, after all, who looted Benin City in 1897, and brought the Benin Bronzes to Europe. The British Museum, with more than 900 Benin Bronzes, has the largest collection in the world. According to Professor Abba Tijani, the head of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), the consequences are clear. He told me Germany’s decision “will greatly impact on the British position. Britain cannot continue to deny that these artefacts are stolen.”

“Born and bred in empire and colonial practice”

The British Museum’s critics, of which there are many, accuse it of hiding behind the 1963 law to avoid its moral responsibilities. Professor Tijani says the legal argument is “an excuse. If the British Museum would advise the government, then the government will accommodate it”. But the British Museum’s 25 trustees, most of whom are appointed by the Prime Minister and one by the Queen, are a traditionally conservative group. In 2019, when the Egyptian author Ahdaf Soueif resigned from their ranks, she cited, amongst other reasons, the British Museum’s refusal to discuss restitution. She complained that a museum “born and bred in empire and colonial practice...hardly speaks”. In private, a British Museum trustee, as well as curators, have told me they are troubled by the issues around imperial loot. But two years after Soueif’s resignation, and despite the intense public debate about colonial legacies, the statements from the British Museum’s press office are as bland and cautious as ever.“Britain cannot continue to deny that these artefacts are stolen.”

Even if the British Museum was inclined to take on this government over the Benin Bronzes, the coronavirus pandemic has weakened its position. The museum typically receives about six million visitors each year. But in 2020 and 2021 it was closed for long periods and received only 160,000 visitors, of whom a mere 3,000 were from overseas. The museum’s admissions and trading income collapsed; down by 93 percent and 97 percent respectively. These losses were mitigated by emergency funding from the government. When Oliver Dowden wrote to museums and advised them not to become involved in “activism or politics”, his letter contained a reminder of their financial dependence on his government. Many curators interpreted this as a thinly-veiled threat. Given all this, it would be surprising if the British Museum’s appetite for political battles with the government was not diminished.

The wish to return objects, forbidden by law

In October 2021, George Osborne took over as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the British Museum. Although Mister Osborne was a Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister) in a previous Conservative government, he is perhaps more liberal than many ministers in the current administration on cultural issues. It is not clear yet what impact, if any, his appointment will have. In the meantime the British Museum’s position on the Benin Bronzes will not change, even as it becomes increasingly isolated within the Benin Dialogue Group of European museums and Nigerian institutions. It is “fully committed”, a source says, in support for a new museum in Benin City, to which it has agreed in principle to lend an unspecified number of Bronzes, and is working on related archaeological projects. It is also committed to greater transparency of its Benin Bronze collection through participation in the Digital Benin project.“Britain’s Conservative government [ ...] has little ideological sympathy with the idea of making amends for the past if that necessitates the breaking up of national museum collections.”

Scottish museums, for example, are not constrained by the same legislation as national institutions in England. The Horniman Museum in London, (with 50 Benin pieces taken in 1897), the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (circa 160 pieces) and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (circa 105 pieces) have all indicated their willingness to discuss returns, as have museums in Newcastle and Bristol. But museums which benefit from government funding, such as the Horniman, are vulnerable to political pressure. A curator at one museum, responsible for a significant collection of Benin Bronzes, told me of a feeling of being trapped between a desire to do the right thing and the need not to provoke the government. Aberdeen University Museum and Jesus College at Cambridge University, were able to take advantage of their greater autonomy in deciding to return individual items to the NCMM.

“A feeling of being trapped between a desire to do the right thing and the need not to provoke the government.“